Natasha Byars, Raquel Munarriz Diaz, and Sandipan Paul

Abstract

This article explores how the early childhood field can support capacity building around equity in the current workforce and build a more diverse, representative workforce at all levels. The authors explore hiring practices, strategies for equipping a diverse workforce, and the actions necessary to realize equity and inclusion through organizational change using interviews with early childhood organizations across the US and data from a project in Tanzania. Affinity groups and Communities of Practice are highlighted as promising practices to promote equity and excellence within organizations and with external partners. The authors provide a diversity-informed framework to critically examine intentional strategies to ensure the field represents the communities being served and continues in the hard yet necessary work of equity in early childhood.

A well-prepared workforce is essential to delivering high-quality early childhood services. Committed, competent workers who engage young children through sensitive, positive, and stimulating interactions make a fundamental difference in children’s learning, mental health, and development. It is therefore crucial that early childhood workers—volunteers and professionals—are valued and supported within the early childhood field.

To further strengthen the workforce, early childhood organizations and partners are working internally and externally to understand equity and disrupt inequitable practices. For this article, we use the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) definition of equity as “the state that would be achieved if individuals fared the same way in society regardless of race, gender, class, language, disability, or any other social or cultural characteristic” (n.d.). In addition, we embrace the Center for Social Inclusion’s framework of racial equity as not only an ideal outcome, but also as the hard work necessary to achieve an equitable world: “As a process, we apply racial equity when those most impacted by structural racial inequity are meaningfully involved in the creation and implementation of the institutional policies and practices that impact their lives” (Center for Social Inclusion, n.d.).

Organizations, networks, and associations are boldly proclaiming their positions on equity, challenging the early childhood field and many others to do better. In 2012, the publication of the Diversity-Informed Tenets gave the infant and early childhood mental health (IECMH) field consistent language, awareness, and a call to deeper action toward diversity, equity, and inclusion (St. John, Thomas, & Noroña, 2012). Rightly so, IECMH was defined as social justice work. In 2019, NAEYC took a significant step by publishing their Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education Position Statement and centered their 2019 Annual Conference on Equity in Early Childhood Education. A key message of their written statement is that all children and early childhood educators have the right to equitable learning opportunities that acknowledge and address historic injustices and marginalization (NAEYC, 2019). Similar to the Tenets Working Group and NAEYC, other organizations (e.g., University of Florida’s Lastinger Center and School Reform Initiative) have written similar position statements on the issue of racial equity and why it needs to be addressed at a structural level.

These statements serve as anchors for early childhood organizations and challenge the field to go beyond their words to the deep, messy, nonlinear, and vital work of advancing equity. This article will explore how all can lead from where they are to support capacity building of the current workforce around understanding and attending to issues of equity and bias. Using the voice of stakeholders in the field and a case example, we unpack the necessary steps to build a more diverse, representative, and inclusive workforce at all levels. Ultimately, we encourage readers to reflect on their own roles as leaders and the opportunities to advance equity in their own context. In doing so, the early childhood field can promote the well-being of all babies and toddlers.

If you have come to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together. —Australian Aboriginal Elder Lilla Watson (as cited in Sojourners, 2009)

To advance racial equity in the early childhood workforce, there needs to be dedicated attention to building an inclusive culture, strengthening policies and procedures to enable equitable outcomes, and creating intentional opportunities for professional development and support (Hanleybrown, Lakshim, Kirschenbaum, Medrano, & Mihaly, 2020). These goals can be put into practice by looking at how organizations hire, how they equip the workforce, and how they realize equity and inclusion through organizational change.

To anchor our discussions, we lean heavily on the Diversity- Informed Tenets (St. John et al., 2012) that were developed with a vision for a workforce in which “all individuals, programs, organizations and systems of care embed principles of diversity, equity and inclusion into their work serving infants, children and families” (Tenets Working Group, 2018). There are 10 tenets in total designed to help “people, organizations and systems of care by offering a set of aspirational principles which we [they] can all strive towards” (Tenets Working Group, 2020). Strategies accompanying each tenet encourage professionals to unpack programmatic and organizational practices and policies and to cultivate self-awareness as a foundation to examining topics of diversity, equity, and inclusion, beginning with the self. Four tenets are highlighted in our chapter–Make Space and Open Pathways (Tenet #9), Allocate Resources to Systems Change (Tenet #8), Champion Children’s Rights Globally (Tenet #2), and Advance Policy That Supports All Families (Tenet #10). These tenets align with the exploration of advancing equity through workforce development.

Diversity-Informed Tenet #9: Make Space and Open Pathways

Infant, child, and family-serving workforces are most dynamic and effective when historically and currently marginalized individuals and groups have equitable access to a wide range of roles, disciplines, and modes of practice and influence. (Tenets Working Group, 2018)

Hiring Practices

To intentionally advance equity, organizations must take stock of their hiring practices. Studies have shown that implicit bias often leads managers to hire others who are like themselves, and that implicit bias is often a stronger force in decision making than objective job qualifications (Elkins-Tanton, 2019; Rivera, 2012). Yet, diverse workforces are more resilient, more adaptive, more creative, better at problem solving (Lorenzo, Voigt, Tsusaka, Krentz, & Abouzhar, 2018; Tsusaka, Reeves, Hurder, & Harnoss, 2017), and, often, more profitable (Iyer & Kirschenbaum, 2019). Standardized interview questions, rubrics for rating candidates, diverse interview teams, and questions that intentionally get at assessing a candidate’s understanding and commitment to equity are all useful tools in increasing equity in the hiring process (Bohnet, 2016; Elkins-Tanton, 2019; Knight, 2017).

To intentionally advance equity, organizations must take stock of their hiring practices. Photo: ESB Basic/shutterstock

For example, Tonia Spence, senior director of Early Childhood Services at the Jewish Board in New York City, says she and her staff ask specific questions at every interview. Crediting Joyce James’s work in the Texas child welfare system, Spence asks all candidates some variation of the question, “Why are people poor?,” as well as other questions focused on diversity and equity, gaining perspective into the candidate’s formulation of the communities within which they might work and the challenges faced. Questions such as these, particularly when used to dig deeper and engage the candidate in a back-and-forth conversation, do more than simply check for whether the right answer is given. They give insight into a candidate’s self-regulation and reflection, their ability to learn, and their ability and willingness to take another’s perspective. “I’m listening and watching… Can you hear me? Can you regulate in this conversation?” (T. Spence, personal communication, February 10, 2020).

Carol Singer, senior director of programs and director of Parenting & Youth Services at Jewish Family and Community Services, East Bay, oversees programs that primarily serve Latinx and African American communities. Although interview panels previously had been comprised solely of supervisors, she now purposefully includes direct staff and people of color to sit in on all interviews. In addition to bringing different perspectives into the hiring process, this inclusion also allows for staff who are from the community to have influence and voice into potential hires. “I want staff to feel comfortable with their communities being served by these people” (C. Singer, personal communication, February 10, 2020).

In Phoenix, Arizona, Early Head Start and Head Start director Mindy Zapata’s efforts to build a workforce that represented the community required new ways of thinking and being for Southwest Human Development. In recruiting for their Child Development Associate (CDA) credential program, hiring family members of Head Start students emerged as a decided priority. Doing so required the organization to not only think deeply about whom they hired, but also how they hired. Because the programs serve a largely immigrant and refugee community, with the intersection of limited incomes, the application and interview process included identifying and tackling potential barriers to an applicant’s success in the position.

The CDA credential program had all of the pedagogical features needed, but our program was set apart by thinking about and supporting soft skills such as coming to work on time, planning around backup care, transportation, negotiating this with a partner. More often than not, [employment] empowered a female in the family and [she might need support in] how to navigate dynamics or tension that might arise. We had to have referrals ready for mental health or counseling services, or [utilize] existing resources if still a current Head Start parent. (M. Zapata, personal communication, February 6, 2020)

Being able to attract applicants from the community required relationship and trust building that took place over time— community members had witnessed that they would be heard and served within the programs that served their children. Noticing that many of the Burmese children in the program were not eating during the day at the center, Zapata sought community input and subsequently introduced rice to the Head Start menu to better reflect community food culture. With a growing number of Somali children in attendance, the center chose to completely remove pork and the word “ham” from menus to allay concerns of families who avoid these for religious reasons. These actions laid groundwork that proved integral to recruiting staff from the community. Prayer rooms were identified for prospective staff, and the organization made space for women to bring male family members with them to interviews, to accommodate requests from the local Somali community. In addition, resources were allocated to cover required employment expenses such as tuberculosis screenings and background checks, as well as to supporting on-site partnerships with local community colleges for CDA program participants to continue their education. Southwest Human Development’s Head Start programs began to be seen as pathways for employment within their local communities, and older siblings and other family members, including men, have been trained and hired. Each of these were changes to business as usual, yet were necessary steps toward a more representative workforce.

Holding Space

It’s all too easy to hire people from diverse backgrounds and then sit back and expect the magic to happen. A passive approach is guaranteed to fail. (Lorenzo et al., 2018)

As organizations work toward more diverse, representative, and equitable workforces, they must also consider how they are making space for those voices. Early childhood organizations

must think about the environment they’re inviting people into. What that needs to look like and what they need to do to make people feel comfortable. And how willing they are to have difficult conversations and how willing they are to hold all of their staff accountable for microagressions and being willing to talk about it. (C. Singer, personal communication, February 10, 2020)

Both affinity groups and Communities of Practice (CoPs) can be strong, relational levers in advancing equity.

Affinity Groups. Affinity groups, or caucuses, are often used in workplaces to create spaces where people of similar identities can come together around particular issues. For underrepresented communities, they can serve as a special place for connection that may not often be found in daily work life (Children’s Day School, n.d.), as well as being spaces of support and healing (Dismantling Racism, 2016). Two of the organizations interviewed, The Jewish Board and Jewish Family and Community Services, East Bay, use affinity groups so that both white staff and staff of color can each reflect upon issues of race and work toward increasing individual and collective commitment to equity within the organizations.

People of color, in circles both within and outside of work, are often put in the role of explaining racism or of representing their own, or other, communities (Thomas-Breitfeld & Kunreuther, 2017). Their vulnerability in such roles as experts or teachers often goes without equal vulnerability from their white colleagues; in fact, it can be met with distress, disbelief, and fragility. Racial affinity groups allow for white staff to do their own work of understanding whiteness, racism, and equity without further perpetuating the burden often put upon people of color (Smith, n.d.). The groups meet regularly “so we can do the work we need to do to have a more inclusive environment and be better allies” (C. Singer, personal communication, February 10, 2020).

CoPs.Beyond working internally to promote equity and excellence, organizations need to support diversity and inclusion as part of their work with external partners. Adopting an equity lens should be infused in all external efforts to support a diverse and inclusive early childhood workforce. Building a pipeline of diverse leaders requires more than recruitment and training. Once in a leadership position, how do managers engage a productive team while building an inclusive culture? Relationship-based strategies that foster true listening, critical feedback, and collaborative problem-solving are needed. A CoP is one relationship based strategy that has proven to work as a vehicle to promote equity and excellence within organizations and with external partners.

Community of Practice members need to feel supported in order to make their beliefs and practice public—requesting, receiving, and offering critical feedback defines the core of a CoP. Photo: Melisa Cardona, © Tenets Initiative. Reused with permission

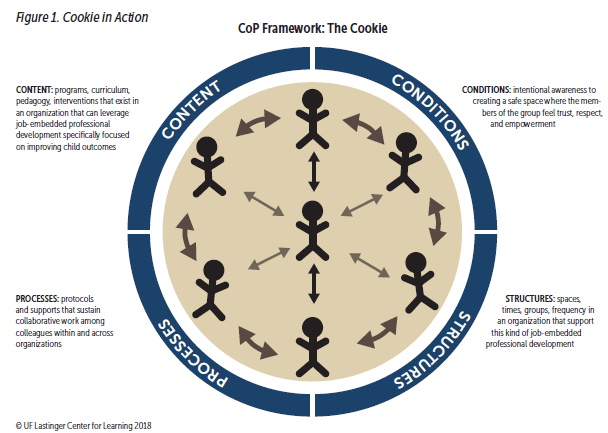

CoP is a term used to describe “groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis” (Wenger, McDermott, & Snyder, 2002, p. 4). The concept of CoPs describes the organic interactions of people interested in learning from one another around any area of shared endeavor. An effective CoP fosters reflection, inclusion, shared wisdom, and critical feedback. It is a space for professionals to gather to question their practice, their beliefs, and their purpose. The University of Florida Lastinger center has created a framework for the effective implementation of a CoP with four key considerations: (1) content, (2) conditions, (3) processes, and (4) structures.

- Content focuses on the shared concern or topic that is bringing people to the table. The content of a CoP is motivated by the issues and concerns that participants are facing.

- A CoP runs on and is sustained by collaboration and shared learning (Dana & Yendol-Hoppey, 2016). Special consideration is given to intentionally creating the conditions of trust and safety necessary for CoP participants to authentically share aspects of their practice. CoP members need to feel supported in order to make their beliefs and practice public—requesting, receiving, and offering critical feedback defines the core of a CoP.

- Content is processed through the use of engaging protocols that focus on equity of voice and job-embedded implications. The regular use of protocols encourages professionals to be intentional, systematic, and disciplined in how they think about and approach their own and each other’s practice (School Reform Initiative, 2017).

- Structure needs to be considered to ensure the members have the time, space, and resources to work collaboratively.

Organizations can use the Cookie Framework (see Figure 1) to guide strategic planning as well as professional development. In Georgia and California, state agencies have used CoP tools and processes in all levels of leadership as a way to gather people to the table and engage them in reflective, critical conversations focused on improving outcomes for children and families. In Florida, CoPs are being used to support practitioners in the field, with more than 400 people attending CoP facilitator institutes in the past 6 years (Rodgers et al., 2018). Within the CoP, the facilitator works to ensure the content, process, structure, and conditions are being considered. Through intentional facilitator moves, the group maintains continual attention to diversity and inclusion.

Diversity-Informed Tenet #8: Allocate Resources to Systems Change

We must be open to doing things differently, sometimes radically so, than we’ve done them in the past. We may have to redefine the very things we thought were basic. —Barriers and Bridges Principles (as cited in Dismantling Racism, 2016).

Changing early childhood systems to advance equity requires an investment of resources, including time, energy, emotion, and money. Individual programs, organizations, and the early childhood field must be brave enough to take an honest accounting of where they still have work to do, and then do it. Although studies have shown that diversity in leadership teams accounts for some of the most significant gains diversifying offers to organizations (Lorenzo et al., 2018), the Race to Lead report (Thomas-Breitfeld & Kunreuther, 2017) found that people of color continue to account for less than 20% of nonprofit and foundation executive director and chief executive officer roles. It also found that this gap is not due to lack of qualifications, education, preparation, aspiration, skills, or background. Rather, it is an issue of systemic racial inequity.

NAEYC is working to address this gap in the local affiliate leadership level. Though committed to equity, the demographics of their local affiliate leadership boards had not changed significantly over the past 20 years, remaining predominantly white (Simmons, 2019). In 2015, NAEYC responded by creating their Affiliate Advisory Council. This national council is made up of diverse members and serves to support inclusion and representation at the affiliate level while also providing recommendations to the NAEYC Governing Board on how to further their commitment to advancing equity, diversity, and inclusion.

Each team, department, and organization can and should examine its own data. Who is being hired? What roles are filled by people of color and those who inhabit other diverse identities? Leadership makeup matters and, in addition to impacting the adaptive capacity of organizations, leadership and staff compositions send messages to staff and communities served. These gaps do not happen by accident and they require conscious, persistent effort to address.

Advancing equity to support a stronger workforce involves risk and discomfort. It may involve holding a position open for longer than expected in order to hire someone who reflects the community, who speaks a needed language, or waiting to hire someone who understands and is committed to advancing equity in their own work. These aspects are not simply nice additions to a portfolio of skills and experience; they are more central and vital to the work than has been historically acknowledged. But this is often uncharted territory for organizations, and it is important to build partnerships and organizational buy-in, as Spence (personal communication, February 10, 2020) pointed out:

Think about stakeholders–who are the stakeholders in doing this work? The people who hold the ability to make decisions—financial, and when things get hard. When you do diversity, equity, and inclusion work, things will pop up–someone will feel ostracized. This just happens. Who are the key stakeholders and decision makers (fiscally and around risk)? Whoever manages risk, have them at the table. You might need to do training with them. You need a budget for this work, so think about where the budget is sitting. Organizationally, who is keeping it held together? (Consider) hiring a chief equity officer.

Diversity-Informed Tenets #2 and #10: Champion Children’s Rights Globally and Advance Policy That Supports All Families

Research is clear that a well-prepared workforce is essential to delivering high-quality early childhood services (Saracho & Spodek, 2007). Committed, competent workers who can create an engaging learning environment through sensitive, positive, and stimulating interactions with young children make a fundamental difference in children’s learning and development (OECD, 2011). It is therefore crucial that early childhood workers are valued and supported (OECD, 2018). Developing a strong workforce includes efficient recruitment; adequate pre-service training; qualifications and career development opportunities; equitable access to high-quality, ongoing professional support for all personnel; and monitoring how these components impact and are responsive to the local context.

Case Example: Interim Workforce Strategy in Mainland Tanzania

The qualifications officially required of preschool teachers in mainland Tanzania are the same as those for any primary grade teacher, which has greatly limited the number of preschool teachers who could be hired with the available funds. In 2013, the national ratio of students to qualified preschool teachers was 158 to 1. To cope with this imbalance, many schools secured local paraprofessionals to teach in preschool classrooms, with salaries paid by families.

The launch of a new education and training policy that extended free, compulsory education to include 1 year of preschool education eliminated the option of parent-funded paraprofessionals, with negative consequences. Many schools were forced to deploy primary teachers to preschool classrooms, in addition to the grades they were already teaching. While this policy resulted in a slight improvement to the qualified preschool teacher to student ratio, it remained at an unmanageable 104 to 1 in 2016. In response, the government developed an interim strategy with the following key points of policy:

- To bridge the gap in current levels of specialization in preschool education, nationwide training was rolled out with the aim of reaching one teacher from every primary school with an orientation on the preschool curriculum and pedagogy.

- Further, a national framework for professional development was approved, and new preschool modules were developed to be piloted in 2018 and rolled out in 2019. The framework provides guidance on how in-service accredited training can be rolled out nationally through a combination of self-study and school-based and cluster meetings, starting initially with a focus on the preschool and early primary levels.

- The option of drawing on paraprofessionals in remote locations and satellite centers is being discussed. Plans have been made to recruit large numbers of paraprofessionals, who will participate in 30-day training programs. Although an official option for their integration into the workforce has not been put in place, longer-term plans include a professional development pathway to enable paraprofessionals to upgrade their qualifications through long-distance learning.

The interim strategy does not call into question the importance of recruiting fully qualified teachers as an important long-term goal for the Tanzanian government. However, in being responsive to the extensive and unmet needs for preschoolers, the immediate focus is placed on improving access and taking advantage of what is achievable with providing further professional development for the existing workforce.

Moving Forward: A Shared Imperative

Advancing equity in the early childhood workforce involves a continuous process of growth and commitment. This work is messy, it is not linear, and it requires continuous reorientation and rebalancing from the status quo. The work is also multifold, concurrently requiring self-reflection and learning, supporting greater equity in the current workforce, and building a pipeline for a more representative workforce. For some, it will require practicing new language or ways of thinking. For others, it is an extension on what has always been known as true. Embracing this work challenges each of us “to learn that points of resistance, both within ourselves and as exhibited by others, are the sources of greatest learning. We must recognize discomfort as a signal for learning rather than an excuse for withdrawal or defensiveness” (Barriers and Bridges, Grassroots Leadership as cited in Dismantling Racism, 2016). Consequently, advancing equity individually and as a field necessitates taking risks, acknowledging mistakes, and having the humility to begin again as pride may be wounded and sense of self will be challenged. As clearly stated by Bates (2018), “We won’t do it ‘right’ and we won’t get it ‘right.’ We will be undone. But don’t let this disappointment get in the way of persistent bold action.”

Advancing equity in the early childhood workforce requires courageous and adaptive leaders. Photo: Matt Parker, © Tenets Initiative. Reused with permission. Photo: Matt Parker, © Tenets Initiative. Reused with permission.

Conclusion

In this spirit, it is important to remember that the mission of ZERO TO THREE is to ensure that all babies and toddlers have a strong start in life. This goal will only be fully realized if, together, we build a workforce that advances equity and access for all families—a task that requires adaptive and courageous leaders. The ZERO TO THREE Fellowship is guided by this vision and trains IECMH leaders to see and cultivate leaders– family members, front-line providers, programs, communities, researchers, advocates, funders and legislators–who can contribute to this work.

There is room for each of us in the work of advancing equity. We need not wait for whole teams, departments, or organizations to respond to the call to advance equity in early childhood professional and workforce development. This is not the time to await better, more ideal circumstances; this work needs each one of us—finding ways to make space, finding partners to join and challenge us. It involves reflecting on how we hold meetings, who is invited, and whose voices are attended to (Heath & Wensil, 2019). It involves taking a hard look at the requirements we list for job positions, who we promote, and who is on our boards.

For those new to the field, advancing equity can start with encouraging others to apply for jobs or consider early childhood professions. It might involve volunteering to serve on a hiring team or suggesting certain topics and presenters for professional development, identifying how it applies to the work. For supervisors and other leaders, it involves creating ongoing professional development opportunities for staff and bringing equity into interviews, team meetings, and supervision. It requires analyzing existing policies and the perspectives from which programs and evaluations are designed.

Equity lies in the minutiae, the mundane as well as in the incredible. No matter the context, there is space to advance equity and inclusion. Boldly, lead from where you are.

Authors

Natasha Byars, MS, MSW, LICSW, is an assistant director at Southwest Human Development, overseeing the Professional Development Institute at Educare Arizona. This innovative effort seeks to address gaps and foster partnerships to provide high-quality early childhood education professional development and coaching across the state, ultimately leading to better, more equitable child outcomes. Ms. Byars also serves as faculty for the Harris Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Training Institute and on the Arizona Early Childhood Professional Development Project ECHO Action Team. Prior to moving to Phoenix, Ms. Byars led the Massachusetts Young Children’s System of Care Project at Boston Public Health Commission, collaborating across the state to integrate infant and early childhood mental health (IECMH) teams into primary care and support IECMH professional development and capacity building in communities and systems. She was a Project LAUNCH clinician and Department of Psychiatry Social Work Fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital, has consulted on international SEL curriculum development, and worked in an Indigenous village preschool in Chiapas, Mexico. Ms. Byars earned a master’s degree in child development from Erikson Institute and a master’s of social work from Loyola University Chicago. She holds the principles of inclusion, representation, and honoring families as central to her work.

Raquel Munarriz Diaz, EdD, has more than 30 years of experience working in early childhood education. She is National Board Certified in Early Childhood. She received her doctorate from Florida International University researching the role of language in early childhood mathematics. Prior to her appointment as professor in residence for the University of Florida (UF) in 2009, Dr. Diaz served as the Miami Science Museum’s project coordinator where she helped develop and disseminate an early childhood science curriculum. Dr. Diaz supported teachers earning a graduate degree in curriculum and instruction. Currently, Dr. Diaz is the implementation success manager for the UF Lastinger Center for Learning. Her current role has her highly involved in supporting the design and facilitation of reflective, job-embedded professional development for educators across the nation.

Sandipan Paul works as education specialist with UNICEF Office for Pacific Island Countries based in Fiji. He provides technical support and advice to the development, implementation, monitoring, evaluation, and reporting of the early learning systems element of the education program, for the purpose of strengthening and expanding systems-level support to country-specific (Pacific Island Countries) and regional goals for early learning. Prior to the current role, Sandipan has been working as international consultant in early childhood development across 17 countries and regional organizations and networks, providing technical support for developing early childhood development policies, strategies, and national plans, competencies, and standards for quality improvement and program evaluations, most of which have with UNICEF Head Quarters and country offices, World Bank, private philanthropies and humanitarian organizations. He has authored several reports commissioned by UNICEF as well as in an international journal titled Early Childhood Matters.

References

Bates, K. (2018). We will be undone: A view on achieving racial equity. Interaction Institute for Social Change. Retrieved from source

Bohnet, I. (2016). How to take the bias out of interviews. Harvard Business Review. source

Center for Social Inclusion. (n.d.). What is racial equity? Retrieved from source

Children’s Day School. (n.d.) Affinity groups FAQ. Retrieved from source

Dana, N., & Yendol-Hoppey, D. (2016). The PLC book. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Dismantling Racism. (2016). Dismantling racism workbook. Retrieved from source

Elkins-Tanton, L. (2019). News flash: People tend to hire people like themselves. Medium. Retrieved from source

Hanleybrown, F., Lakshim, I., Kirschenbaum, J., Medrano, S., & Mihaly, A. (2020). Advancing frontline employees of color: Innovating for competitive advantage in America’s frontline workforce. Foundation Strategy Group. Retrieved from source

Heath, K., & Wensil, B. F. (2019). To build an inclusive culture, start with inclusive meetings. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from source

Iyer, L., & Kirschenbaum, J. (2019). How companies can advance racial equity and create business growth. Foundation Strategy Group. Retrieved from source

Knight, R. (2017). 7 practical ways to reduce bias in your hiring process. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from source

Lorenzo, R., Voigt, N., Tsusaka, M., Krentz, M., & Abouzahr, K. (2018, January 23). How diverse leadership teams boost innovation. Boston Consulting Group. Retrieved from source

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2019). Advancing equity in early childhood education position statement. Retrieved from source

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (n.d.) Definition of key terms. NAEYC. Retrieved from source

OECD. (2011). Starting Strong III: A quality toolbox for early childhood education and care. Paris, France: Starting Strong, OECD Publishing. source

OECD. (2018). Engaging young children: Lessons from research about quality in early childhood education and care. Paris, France: Starting Strong, OECD Publishing. source

Rivera, L. A. (2012). Hiring as cultural matching: The case of elite professional service firms. American Sociological Review, 77(6), 999–1022. source

Rodgers, M. K., Qiu, Y., Leite, W., Hagler, N., Mathien, T., Schroeder, S.,… Fish, G. (2018). Early learning performance funding project: Final evaluation report 2017–2018. Tallahassee: Florida Office of Early Learning.

Saracho, O. N., & Spodek, B. (2007). Early childhood teachers’ preparation and the quality of program outcomes. Early Child Development and Care, 177(1), 71–91.

School Reform Initiative. (2017). Why protocols. Retrieved from source

Simmons, G. (2019, November). Affiliate leadership Day. Presented at National Association for Education of Young Children National Conference, Nashville, TN.

Smith, K. (n.d.). Race caucusing in an organizational context: A POC’s experience. CompassPoint. Retrieved from source

Sojourners. (2009, July 22). Voice of the day: Lilla Watson. Retrieved from source

St. John, M. S., Thomas, K., & Noroña, C. R. (2012). Infant mental health professional development: Together in the struggle for social justice. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 33(2), 13–22.

Tenets Working Group. (2018). Diversity-informed tenets for work with infants, children, and families. Chicago, IL: Irving Harris Foundation.

Tenets Working Group. (2020). About the Tenets Initiative. Irving Harris Foundation. Retrieved from source

Thomas-Breitfeld, S., & Kunreuther, F. (2017). Race to lead: Confronting the nonprofit racial leadership gap. Building Movement Project. Retrieved from source

Tsusaka, M., Reeves, M., Hurder, S., & Harnoss, J. (2017). Diversity at work. Boston Consulting Group Henderson Institute. Retrieved from source

Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. M. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice. Boston. MA: Harvard Business School Press.