Anissa Chitwanga and Teresa Ostler, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Abstract

Told through the lens of Malawi customs, culture, and taboos, the authors describe the life experiences and mental health needs of Pilirani, a young Malawi Slay Queen, and her children. The article reveals the adversities she faced, her dreams for her children, how she and her children fared, and what helped them at various junctures in their lives. Pilirani kept her deep-seated fears of HIV secret, but then found a way to share. The authors draw on the notion of Ubuntu (“I am because we are”) to describe how peer support, trust, and sharing helped to address Pilirani’s stigma, shame, and mistrust, and provide a pathway toward healing.

When I (Anissa Chitwanga) was a child, my cousin told me a lot about a girl named Pilirani. Pilirani was 9 and had recently moved to the big city of Lilongwe from Ngonami, a poor village in Malawi. She ended up in my cousin’s classroom at school. Since that time, at any family gathering, my cousin talked nonstop about Pilirani and her life.

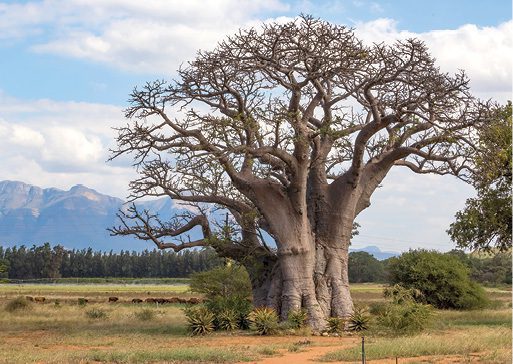

Why I was fascinated by Pilirani, I don’t know. Maybe it was the meaning of her name. In my language, Pilirani means “perseverance.” Maybe it was because Pilirani’s mother was left behind in Ngonami and lost to her, or because her wealthy father swooped in and took her to the city after he had married her stepmother. Maybe it is because she ran away and became a Slay Queen. This means that, in exchange for sex, a woman enters into a relationship with a Blesser, usually an older man between ages 30 and 70, who provides her with wealth—even when her father did not support her decision. Was it the courage and fearlessness she had to date someone older to provide for her needs, something I never had the courage and heart to do? Maybe it was her high self-esteem that she was beautiful and could find an older man who gave her money and spoiled her for sex and companionship. Maybe it is because she reminded me of the baobab tree in my country, an ancient tree species that predates man and the splitting of the continents over 200 million years ago.

The Baobab Tree

Everyone in Malawi knows the baobab tree. The baobab lives almost forever. Some sources say 500 years, yet others say its lifespan is 2,000 years. It thrives even in dry, arid lands, storing water in its enormous trunk which grows up to almost 60 feet in circumference and 90 feet in height. In the old times, people used to place sacrifices under the trees for the Gods. Its roots and bark are still used today for medicinal purposes.

In many African countries, the baobab is a symbol of life and positivity as it survives where little else can thrive. Baobab trees have hollow trunks with stems growing out all over them. They look like they have been stuck upside down in the earth with their roots reaching for the sky. Stories abound as to why the tree looks the way it does. One creation myth says that when God planted the baobab in the earth below, it kept walking, so God replanted it upside down to stop it from moving. In another story, God gave every animal a tree to plant. Disappointed with the baobab, the hyena stuck the tree upside down into the ground.

Pilirani’s life was upside down even for me since I had experienced a chaotic life after my mum’s death. Maybe the wooden spoon my grandmother gave me to keep in my window to ward off evil spirits protected me. But the spoon didn’t keep my grandma from developing dementia, nor did it bring my deceased father back. But now I am getting ahead of myself. All I know is that I listened to every story my cousin shared with me about Pilirani and her life.

Malawi

You must know already that Pilirani comes from Malawi, a small landlocked country in southeastern Africa. Yes, some people have a lot of wealth in Malawi, especially in the big cities. But the rural countryside, where almost 80% of people live, is different. If you go there you know why Malawi is considered one of the poorest countries in the world. Many children have little access to education and health care. Clean water and sanitation are also huge everyday challenges. Extreme drought due to rising temperatures makes it hard for parents to grow crops and food. As a result, many children suffer from severe malnutrition.

Patriarchy is firmly entrenched in the culture and traditions, meaning that women and girls are still mostly subordinated. Men make decisions and the destiny of women is to get married, bear children, and serve their husbands and society. Not that I agree with this. I’m just telling you outright what it is like.

Some young girls and women from poor areas of sub-Saharan Africa escape poverty and hunger by becoming Slay Queens. Girls as young as 13 may become Slay Queens in Malawi. This occurs in poor rural areas (Ranganathan et al., 2018), but also in young girls in college, who seek a wealthier, more prestigious lifestyle (Zawu, 2020).

The practice leaves girls and women highly prone to intimate partner violence, social stigma, and isolation (Hoss & Blokland, 2018; Mampane, 2018), early pregnancies, and serious and often long-term mental health problems (Goso et al., 2020). And then there is HIV. Malawi has one of the highest rates of HIV in the world (Nutor et al., 2020). Adolescent girls and young women between 19 and 20 years old are at high risk of contracting HIV, especially if they have an older partner or multiple partners (Daniels et al., 2021).

Pilirani’s Story

I will tell you Pilirani’s story now, all that I remember about her, her young children, and her dreams for all of them. Pilirani’s parents’ relationship never worked out. It failed at the outset. Her father had dazzled Chifundo, Pilirani’s mom. But he also left her pregnant in the village and moved on to the big city and to other women. When he finally married years later, Pilirani’s father returned to the village and took Pilirani into his new home in the city.

Don’t Beat My Only Child

I never heard what Pilirani’s mother felt when her daughter was taken away to the city. From my mother’s experiences, I know she only wanted the best for Pilirani. Maybe she asked herself “Why keep her in the village when I can barely feed her or give her basic daily needs?”

Whenever I think of Chifundo’s feelings, the song “Sewele” comes to mind. The song is a prayer to in-laws when one’s child is getting married. It begs them not to “beat nor slaughter their child.” “Sewele” is a call to “save the only child I have and how I fasted for 4 long weeks so this child could live” (Mbenjere, 2008). Maybe Chifundo felt that the song was for the time when Pilirani married. But maybe it was her plea to Pilirani’s stepmother who was now going to take up the role of a mother to Pilirani.

Pilirani’s years of adolescence were hell. She complained bitterly to my cousin about her stepmother, Gloria, but also about numerous other lady friends her father would bring home with him, which always upset Gloria and brought out the worst in her. The girlfriends were demanding, petulant, and big money grabbers, Pilirani said. They soon became too much for both Pilirani and her stepmother, who grew bitter and angry at her husband’s galavanting. She beat Pilirani, but also beat one of the girlfriends so badly that she was hospitalized. Pilirani’s stepmother went to jail, leaving Pilirani without a mother figure and traumatized both by the incident and the gossip from the neighborhood.

After that, Pilirani was again left alone but sometimes a nanny was there. Throughout this time, numerous women that her father desired came in and out of the household. Being left alone and a teenager, Pilirani became notorious and started dating, mostly men older than her.

Persevere Where You Are Going

Pilirani’s path ahead entailed much hardship, perseverance, and need. Although I don’t know why, but as I write this, I think about the song “Kapilire,” a Malawi song that is sung to brides on their wedding day to accompany them on the way ahead. The song reminds and encourages a young bride that she is embarking on a difficult journey that needs perseverance. Maybe this song accompanied Pilirani in her thoughts as she stayed in her father’s house during all the trials and tribulations, or when she was with her husband experiencing all the atrocities she went through. This is the song in my language:

Kapilire unka iweko

Kapilire unka iweko

Kumeneko kuli ana

Osasamba, amamina, amanthongo

Kapilire iwe

The song talks about “persevering” where you are going. It talks of “kids being in your future”, and about harsh realities of life, about kids with “boogers and eye gunk.” But the song implores you to persevere.

George was a Blesser, an older man who provided material advantages, support, and money to Pilirani for sex and companionship. Pilirani, the young Slay Queen, entered into the relationship with dreams and hopes of a family, wealth, and status (Thobejane et al., 2017; Zawu, 2020). Her husband’s true colors were revealed when she moved in with him as a wife.

George began to beat Pilirani and, as had her father, had serial relationships with other women. Pilirani became pregnant for the first time. Unfortunately, they lost the baby. Not long after, Pilirani became pregnant again with her daughter, Lissa, but then found out at her first prenatal checkup that she was HIV positive. In denial, her husband refused to take medication or to believe her. He thus grew sick with AIDS and died, but before that happened, Pilirani had just given birth to Lissa.

Pilirani soon found herself in a complex relationship with her husband’s family, who maltreated her in many ways. They moved her out of the house she had lived in with George, and then claimed the property, her belongings, and almost all she owned, leaving her and Lissa homeless and destitute. They moved her into the home of one of George’s sisters where she was subject to more emotional and mental abuse.

Pilirani tried to return to her father, but he forbade it. She sought out her mother in Ngomani. But Chifundo urged her to leave, saying, “I can’t support you and can’t even feed you. You will starve to death here. I can’t have you here especially now that you have tasted the sweetness of city living. Your child will have no future here.” In words, gestures, and thought, Chifundo pleaded to her daughter to persevere even in face of her harsh life ahead. She also contacted my cousin, pleading for her to take Pilirani in, if even for a short time.

Pilirani and Lissa ended up living with my cousin for a year. After that, she moved from one temporary place to another, supporting herself through monetary support from older men or “Blessers” in exchange for sex. This left Lissa often alone for periods of time without the support and safety of a mother. She eventually met and married a Blesser (John), a man twice her age and gave birth to Chimwemwe, her third (second living) child. Chimwemwe’s name means “happiness.”

To help keep herself afloat financially, Pilirani started selling plastic kitchen utensils. But John often took the money Pilirani earned. He also abused her and began seeing other women. When she returned home from a funeral one day, Pilirani found her husband had left, taking everything she owned with him from the house. She again started supporting herself and her young children as a Slay Queen, while trying to run her small business on the side.

The Baobab lives almost forever. Some sources say 500 years, yet others say its lifespan is 2,000 years. It thrives even in dry, arid lands, storing water in its enormous trunk. Photo: shutterstock/Rich T Photo

Longings and Dreams

I left out a lot about feelings in my story of Pilirani’s life, but I often thought about what she might have felt when she left her mother, when she moved in with her dad, or when she married a wealthy man twice her age and lived in a huge house with everything anyone would want. I wondered, too, what she felt when she found out she had HIV, when her baby was born and died, when her husband passed away, and when she lived with my cousin before becoming a Slay Queen again. Over the years, I heard a little about her young children, too, and wanted to know what they were feeling, how they fared and coped, what kind of mother Pilirani was, and what kind of dreams she had for them.

I recently contacted my cousin to learn more, and she put me in contact with Pilirani. Pilirani was happy to share her story with me. She wanted others to hear her story and know what she and other women had gone through. In our conversations, she told me many things about how she felt, how she coped, and how she negotiated her way through life with her children.

When asked about how she felt when she was going through all the torment and torture that she endured, she said it was mostly her children that kept her going. She felt that she had to endure all that because her children needed her to be strong to take care of them.

Pilirani recalled how hard it was to bottle up and suppress her feelings just to seem strong on the outside. There were times she couldn’t even eat, wondering where does the appetite come from? “How does one get hungry amidst all these atrocities?” she asked me. At times she wished she could just vanish with her children, or maybe wake up from this nightmare.

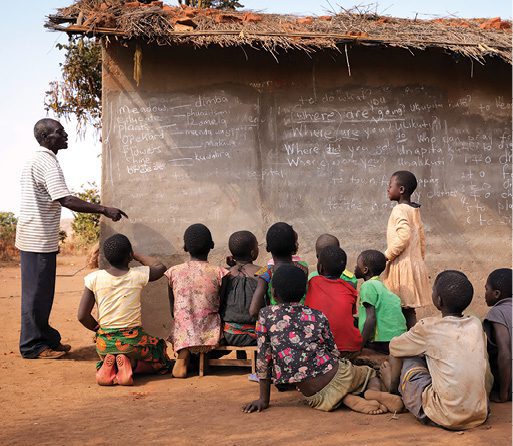

I never heard what Pilirani’s mother felt when her daughter was taken away to the city. Maybe she asked herself “Why keep her in the village when I can barely feed her or give her basic daily needs?”. Photo: shutterstock/hecke61

In this context, she talked quietly about one of her sisters-in-law who was good to her. “A friend,” she said. This sister-in-law saw her needs and would buy necessities for her and her baby when the others were not around. She was there to listen to her and offer comfort and support. “I suppose everyone can’t be bad, there are some good people out there and I am forever grateful to her wherever she may be.”

Pilirani talked at length about her longing for support. At times, she thought about going to court or some organizations that assist women in such situations to at least help her get back the property and money that was grabbed from her after her husband passed. But she was always hesitant when she thought that these actions will all require money, money that she did not have.

Pilirani said,

You know to get anything done in this country you need money; the court clerks need bribes to assist you. And I didn’t have the money. I needed transport money to keep going to the organizations or the court because, you know too well, they won’t solve this in one visit. And this is money that I didn’t have, I was struggling to even buy milk for my baby or even feed myself.

You might wonder where she got the strength to carry on. When all else fails, sometimes the only solace is to trust something or someone larger and stronger than you. Thus, she sought refuge in God and visited a certain prophet. The prophet discouraged her from pursuing any legal action or attempting to claim all that was taken from her and her baby. She said she was told that God had better plans for her and that she should let go of the past and trust God to give her a new beginning and a better future. When my cousin reached out to her and even sent her transport money to move in with her, she figured it was all God’s plan and God’s way of taking care of her.

Pilirani shared how hard it has been on her children to cope with having an absent and deceased father. Lissa still doesn’t understand where her father is nor where he went and why. “It was hard to even explain to Lissa as she grew older about where her father was.” Lissa always admired other kids when they talked about their dads and often wondered why she didn’t have a dad. Pilirani says she now encourages her girls, Lissa and Chimwemwe, to work hard in school and that education is their best option to success and a better future. Pilirani says her dream to see her children succeed is what keeps pushing her to provide for them as long as God keeps her alive.

A Story in a Story: Breaking the Cycle

Life trajectories can cruelly repeat themselves. Adversity for young Slay Queens often leads to more tribulations (Chilanga et al., 2020). But there can also be moments where cycles are broken. I will now tell you a story that helped me see a way to break the cycle of stigma.

The story is about another young Slay Queen named Blessings who moved in with Pilirani not too long ago. At 17 years old, Blessings married a man more than twice her age. Blessings stayed with her husband for 4 years. They had a house, a car, everything she ever dreamt of. After 2 years, her husband hired a maid. Not too long after, Blessings was kicked out of the marital suite and the maid moved in. Her husband married the maid and beat Blessings, who left after her husband took her clothes, her phone, and her money.

As Pilirani spoke with me on the phone, Blessings asked to share her story, too. The two stories differed in important ways, but they had similar beginnings, and similar turning points suggesting that deep-seated patterns were playing out again and again over time and place.

The Parts Left Out

Some parts are left out of life stories. They are not mentioned or talked about because they are too uncomfortable or painful, too stigmatizing and dangerous to share with others or even to fully admit to oneself. As I thought through my memories of Pilirani, I began to reminisce that I had hidden from others my fears about my own mother having and dying of AIDS.

HIV and mental illness remain highly stigmatized in Malawi and sub-Saharan Africa even after Nelson Mandela spoke openly about HIV and AIDS when his son, Makgatho Lewanika, died due to complications from AIDS. Mandela did not know his son had HIV until 6 months before he died. After that, he defied the stigma, telling his people “Let us give publicity to HIV/AIDS and not hide it, because the only way of making it appear to be a normal illness just like TB, like cancer, is always to come out and say somebody has died of HIV.”

In Malawi and other sub-Saharan African countries, you don’t easily tell anyone that you or a relative or close friend have HIV (Kalembo, 2017; Motsoeneng, 2021). People would avoid you, gossip, think poorly of you. It is like a shaming and shunning together. You feel very alone and wronged, like you have a horrible, stigmatizing disease. Most of all, having HIV is terrifying. Having HIV and being pregnant is tormenting. You worry you will die. You worry about your baby. Why would you ever open up when people would gossip and distance themselves even more from you?

Funerals, Sharing, and Hope

At a recent funeral, Pilirani and Blessings met Asante, another Slay Queen, who had lost her partner to HIV. Since that time, she had moved on to a better life with her children. This chance meeting with an acquaintance led to a surprising outcome. Together, the three women sat together on a bench and began to share what it meant to have HIV. They opened up and talked about what their fears were, how devastated they often felt, and how they worried they would transmit HIV to their child.

HIV is intricately linked to depression, anxiety, and other mental illness conditions (Simoni et al., 2011). Antiretroviral therapy can help reduce new cases of HIV, but Malawi is not a country with a lot of resources for mental health. Bringing about real changes will require health literacy—raising awareness of the links between gender violence, HIV, and mental illness. It will require fostering a sense of empowerment in women. It will require capacity building for community-based health care providers to learn about mental health issues in mothers with young children, linkages between schools and community health clinics, and competency-based training to develop capacity for professionals working in these areas to respond effectively.

But creating change starts with disclosure, something which is often difficult, especially for a Malawian Slay Queen. It is difficult because of perceptions of what is inappropriate sexual behavior and that people with HIV are responsible for the infection and its spreading, due to its associations with death and because it can be life threatening (Bos et al., 2013; Kamen et al., 2015; Vranda & Mothi, 2013). Parents may fail to tell their children because they are afraid the child won’t keep this secret (O’Malley et al., 2015). To protect themselves, they conceal the diagnosis. In so doing, they remain isolated, may internalize the stigma, may not get tested for HIV, or may fail to seek out needed help.

Pilirani, Blessings, and Asante found it “freeing” to open up, to let the pain inside out with someone who could understand, to stop bottling up what seemed like a horrible cancer inside. The three women found strength and hope in sharing their stories with each other.

Ubuntu

The Zulu word Ubuntu means “I am because we are.” In essence, this word or philosophy emphasizes the importance of community and sharing. It speaks of deeply held values in Africa of personhood being rooted in interconnected with others (van Breda, 2019), of humaneness, and of being a person through relationships with other people (Mbedzi, 2019). The concept also implies a need for social justice (van Breda, 2019).

I often thought about Pilirani’s words about what had helped her. Staying with my cousin helped. Having a sister-in-law see her needs helped. Sharing with her children her dreams that they would go to school helped them. Openly sharing her experiences with Blessings and Asante made a huge difference. Pilirani also longed for help in telling her children about their fathers, HIV, what had happened, how she had persevered,

and how she had fought for her children so they could have a better life.

The Zulu word Ubuntu means “I am because we are.” Ubunto speaks of deeply-held values in Africa of personhood being rooted in interconnectedness with others. Photo: shutterstock/Oxford Media Library

The conversation at the funeral resonates with other work on HIV in Africa, which is re-thinking HIV disclosure as Ubuntu (Lubombo, 2018). In this approach, disclosure about HIV is construed as speech acts which invite others to dialogue. By sharing, individuals give witness to each other’s experiences, fears, hopes, dreams, and disappointments, thereby obligating the other to “explore mutual potential for life” (p. 9). In this process, people begin to recognize the other’s experiences, begin to see and experience that we are all human and that HIV is part of the human experience. Such dialogues are becoming part of social work practice in sub-Saharan Africa (van Breda, 2019). They create interactions that are accepting and supportive and that encourage joint action to address people’s needs.

The ability to share and trust are key tenets of attachment theory (Bowlby, 2005). Support, trust, and sharing are immensely important to parenting, too. Close others can be sought out for help. They can provide a critical safety network (Bifulco & Thomas, 2012), and help a parent regulate their own anxiety and stress so that they don’t bear the brunt and stresses of parenting alone (Bowlby, 2005). “An expectation resulting from an interactive process of human concern and caring” (Bruhn, 2005, p. 311), trust is key to healing and growth.

Sharing and dialogue can carry risks if they are not accompanied by respect, ethics, and humanity (Ewuoso, 2020). They can lead to more discrimination, stigma, and harm, especially if people are blamed for contributing to high rates of HIV infection in communities (Chilanga, 2020).

The peer support we described emerged spontaneously in a small sisterhood of Slay Queens. It started in support my cousin gave Pilirani and in support Pilirani gave to Blessings. Trust, support, and sharing alone will not solve HIV and mental health conditions. But they are a first humane pathway that must be nurtured and supported to help the children of today and parents of tomorrow.

Authors

Anissa Chitwanga is a 4th year doctoral student in the School of Social Work and a teaching assistant for an undergraduate social work course on Diversity, Identities and Issues in Social Work at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She is a young Malawian qualitative researcher and mother. Her research has focused on access to public benefits by minority groups and immigrants, simulation as a learning tool to promote social work ethics and values, as well as unhealthy sexual relationships between young women and older men known as the Blesser/Slay Queen Relationships.

Teresa Ostler, PhD, is a professor in the School of Social Work and director of the master’s of social work program at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. A 2001–2002 ZERO TO THREE Mid-Career Fellow, she loves qualitative research, life stories, using live simulations as a modality for teaching social work students about social justice in relation to clinical competencies, gardening, and grandchildren.

Suggested Citation

Chitwanga, A., & Ostler, T. (2022). Experiences and dreams of a young Malawi Slay Queen and her children: How peer support, trust, and sharing can address stigma, mistrust, and shame. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 43(2), 13–18.

References

Bifulco, A., & Thomas, G. (2012). Understanding adult attachment in family relationships: Research, assessment and intervention. Routledge.

Bruhn, J. G. (2005). The lost art of the covenant: Trust as a commodity in health care. The Health Care Manager, 24(4), 311–219.

Bos, A. E., Pryor, J. B., Reeder, G. D., & Stutterheim, S. E. (2013). Stigma: Advances in theory and research. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(1), 1–9.

Bowlby, J. (2005). A secure base. Routledge.

Chilanga, E., Collin-Vezina, D., Khan, M. N., & Riley, L. (2020). Prevalence and determinants of intimate partner violence against mothers of children under-five years in Central Malawi. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–14.

Chilanga, Y. (2020). When the hyena wears darkness: Ubuntu as a barrier in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Journal of Contemporary African Philosophy, 1, 59–74.

Daniels, E., Gaumer G., Newaz, F., & Nandakumar, A.K. (2021). Risky sexual behavior and the HIV gender gap for younger adults in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Global Health Reports, 5, 1–11.

Ewuoso, C. (2020). Ubuntu philosophy and the consensus regarding incidental findings in genomic research: A heuristic approach. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 23(3), 433–444.

Goso, M., Matinise, O., & Kheswa, J. G. (2020). Financial deficit as a cause for dependent sexual behaviour among female students in academic campus: An institutional case study. Journal of Human Ecology, 70(1–3), 79–89.

Hoss, J., & Blokland, L. M. E. (2018). Sugar daddies and blessers: A contextual study of transactional sexual interactions among young girls and older men. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 28(5), 306–317.

Kalembo, F. W. (2017, October). Psychosocial and health system factors in disclosure of HIV status to children living with HIV in Malawi: A formative evaluation of disclosure resources [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Curtin University.

Kamen, C., Arganbright, J., Kienitz, E., Weller, M., Khaylis, A., Shenkman, T., Smith, S., Koopman, C., & Gore-Felton, C. (2015). HIV-related stigma: Implications for symptoms of anxiety and depression among Malawian women. African Journal of AIDS Research, 14(1), 67–73.

Lubombo, M. (2018). Re-thinking HIV disclosure as ubuntu: Towards a social theory of communicative responses to the sub-Saharan epidemic. African Renaissance, 15(3), 9–28.

Mampane, J. N. (2018). Exploring the “Blesser and Blessee” phenomenon: Young women, transactional sex, and HIV in rural South Africa. SAGE Open, 8(4), 215824401880634. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018806343. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2158244018806343

Mbedzi, P. (2019). Ecosystems. In A. D. Van Breda & J. Sekudu (Eds.), Theories for decolonial social work practice in South Africa. Oxford University Press South Africa.

Mbenjere, L. (2008, March 12). Sewere [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rj8_NlVQgaY

Motsoeneng, M. (2021). The experiences of South African rural women living with the fear of intimate partner violence, and vulnerability to HIV transmission. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 15(1), 132–142.

Nutor, J. J., Duah, H. O., Agbadi, P., Duodu, P. A., & Gondwe, K. W. (2020). Spatial analysis of factors associated with HIV infection in Malawi: Indicators for effective prevention. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–14.

O’Malley, G., Beima-Sofie, K., Feris, L., Shepard-Perry, M., Hamunime, N., John- Stewart, G., Kaindjee-Tjituka, F., & Brandt, L., for the MOHSS Study Group. (2015). “If I take my medicine, I will be strong”: Evaluation of a pediatric HIV disclosure intervention in Namibia. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 68(1), e1.

Ranganathan, M., Heise, L., MacPhail, C., Stöckl, H., Silverwood, R. J., Kahn, K., ... & Pettifor, A. (2018). ‘It’s because I like things... it’s a status and he buys me airtime’: Exploring the role of transactional sex in young women’s consumption patterns in rural South Africa (secondary findings from HPTN 068). Reproductive Health, 15(1), 1–21.

Simoni, J. M., Safren, S. A., Manhart, L. E., Lyda, K., Grossman, C. I., Rao, D., ... & Wilson, I. B. (2011). Challenges in addressing depression in HIV research: Assessment, cultural context, and methods. AIDS and Behavior, 15(2), 376–388.

Thobejane, T. D., Mulaudzi, T. P., & Zitha, R. (2017). Factors leading to “blesser- blessee” relationships amongst female students: The case of a rural university in Thulamela Municipality, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Gender and Behaviour, 15(2), 8716–8731.

van Breda, A. D. (2019). Developing the notion of Ubuntu as African theory for social work practice. Social Work, 55(4), 439–450.

Vranda, M. N., & Mothi, S. N. (2013). Psychosocial issues of children infected with HIV/AIDS. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 35(1), 19–22.

Zawu, R. (2020). The rise and normalization of blessee/blesser relationships in South Africa: A post-colonial feminist analysis [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Stellenbosch University.