Martha G. Welch and Elizabeth S. Markowitz, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York; and Marc E. Jaffe, Children’s Learning Centers of Fairfield County, Stamford, Connecticut

Abstract

The Nurture Science Program (NSP) at Columbia University Irving Medical Center completed a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of Family Nurture Intervention (FNI) among mothers and prematurely born infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. Results showed FNI had significant neurodevelopmental, behavioral, and physiological effects on mothers and infants out to 5 years. Now, the NSP is conducting an RCT of a group model of FNI in a preschool-aged population (Group FNI-Preschool) at Children’s Learning Centers of Fairfield County (CLC). This article describes the goals of the study, the underlying theory, and the general methods of the mother–child intervention.

This article describes a study of a group model of Family Nurture Intervention (FNI) in a community preschool education center. The Nurture Science Program (NSP) and Children’s Learning Centers of Fairfield County (CLC) jointly designed the study over a 12-month period. In partnership with Yale’s Center for Emotional Intelligence between 2011 and 2016, CLC successfully embedded the RULER Program ( www.ycei.org/ruler) into their standard teaching program. The CLC staff concluded that, while the focus on emotional intelligence helped children identify and name their emotions, it did not fully address the growing incidence of emotional dysregulation and disruptive behaviors in the classroom. CLC and NSP agreed to test whether establishing parent–child emotional connection through Family Nurture Intervention (FNI) could address the problem. Questions of interest to CLC: (1) whether CLC mothers would participate in the group model; (2) whether the model actually reduces disruptive classroom behavior; and (3) whether it is feasible to embed a group model of FNI into CLC’s standard curriculum.

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) of FNI among prematurely born infants and their mothers in a hospital setting found significantly improved behavioral and physiological outcomes for both mother and infant (Porges et al., 2019; Welch & Myers, 2016). Since then, the NSP has validated a novel assessment tool to measure emotional connection: the Welch Emotional Connection Screen (WECS; Hane et al., 2019). The NSP is using this tool in replication and effectiveness FNI-NICU trials and in FNI-Preschool studies.

The current study includes a battery of physiological and behavioral assessments of mother and child. Mothers complete questionnaires probing their child’s social–emotional and cognitive development and behavior, and their own depression and anxiety symptoms. In addition, teachers of participating children complete a validated tool for tracking preschool child behavior in the classroom (Croft et al., 2015). Study staff members rate mothers and their children during the session on the WECS, and blinded NSP coders also rate each dyad’s emotional connection at assessment time points.

Theoretical Framework

The foundational premise of FNI is that infants and young children do not self-regulate, either emotionally or physiologically. Rather, the emotional and behavioral well-being of infants and young children requires co-regulation by a caring adult. These ideas are elucidated in calming cycle theory (Ludwig & Welch, 2019; Welch, 2016; Welch & Ludwig, 2017a, 2017b), which introduces two new constructs. Emotional connection describes the adaptive, prosocial relationship between mother and infant/child, which is manifest when the pair share emotions—both positive and negative. Autonomic co-regulation describes the corresponding harmonious autonomic states of mother and infant/child that underlie emotional connection. For this reason, we use the combined autonomic emotional connection to define the optimal state of mother–child relating.

According to calming cycle theory, physical and emotional interactions between mother and child involve two distinct, measurable and sub-conscious responses—one behavioral and one physiological. The behavioral responses include measurable motivation indicators, such as physical movement (toward each other), vocal–facial communication, and the level of sensitivity and reciprocity. The physiological response includes measurable biological indicators, primarily heart rate and heart rate variability, which are modulated by the autonomic nervous system. The physiological and behavioral responses correlate with one another and occur more or less simultaneously.

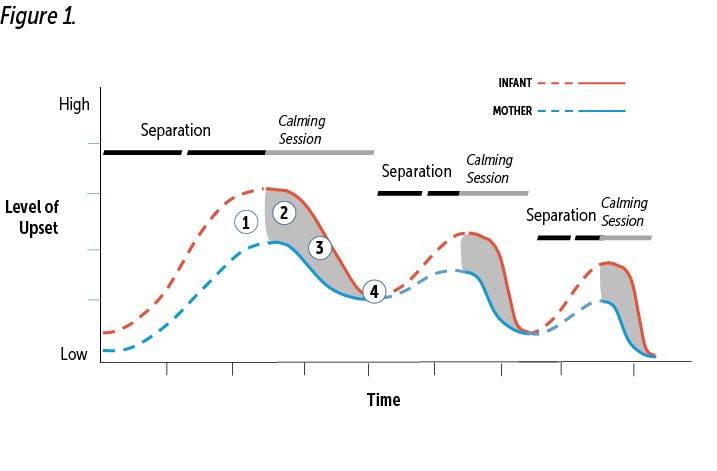

These paired responses of mother and child are dynamic and constantly changing, cycling on a daily basis through stages of upset and calming (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual Representation of Calming Cycle Theory During a calming cycle, mothers and children cycle through: (1) separate mother and child distress, (2) mutually shared distress, (3) mutual resolution of distress, and (4) mutual calm that may include periods of eye contact, physiological calming, or both. Over time, calming cycle interactions will lead to more rapid reductions and lower levels of discomfort and distress in both the mother and the child. (Note: the break in separation line indicates mother–child separation times may vary widely.)

Thus, autonomic emotional connection is a state, not a trait. When the calming part of the cycle does not occur, the result is autonomic dysregulation and symptomatic behaviors. The repeated calming cycles help the mother and child reach a state of relational, mutual calm, thereby restoring the adaptive physiological state of “co-regulation” and its corresponding adaptive/pro-social behaviors manifest as autonomic emotional connection, including eye contact and reciprocal social engagement that is sensitive to the feelings of the other.

Study Assessment Measures and Hypotheses

Primary outcome measures included assessment of behavior and physiology of the child and mother at three time points: prior to enrollment into the study, upon completion of the intervention, and at 6-months after initial measurements. (See Box 1 for a list of the measurements.)

Assessments include conventional measures of mother and infant behavior and physiology, as well as novel measures of relational health and the mother’s perception of socioemotional support:

- Changes in maternal stress and resilience—the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (Hughes et al., 2017)

- Parenting Stress Index 4th Edition Short Form (Abidin, 2012)

- Relationship Scales Questionnaire (Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994)

- Changes in maternal perception of familial support—the Mother’s Socioemotional Support Circle (Austin et al., 2021)

- Classroom behavior and child development—Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman & Goodman, 2009; parent-and teacher-report), as well as the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000)

- Physiology—vagal tone (high frequency heart rate variability), heart rate, respiratory rate, and galvanic skin response

We hypothesized that Group FNI-Preschool would positively change the autonomic physiology of mother and child when the two are together. We hypothesized that joint mother–child behaviors would improve at home and in school. We also hypothesized that intervention mothers would show a decrease in symptoms of anxiety and depression at the 2 months follow-up.

Standard Curriculum

All participants in this study completed the standard CLC curriculum, whether in the Standard Care or FNI-Preschool group. The CLC standard curriculum uses the Connecticut Early Learning and Development Standards (Connecticut Office of Early Childhood, 2020a) and the Connecticut Preschool and Assessment Framework (Connecticut Office of Early Childhood, 2020b), both of which focus on children’s progress within a set of developmental domains. CLC’s Head Start Program uses the Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework in accordance with Head Start standards (Head Start, 2020). Child Development and School Readiness programs use the Connecticut Data Observation and Tracking System, and CLC’s Head Start and Early Head Start sites use the Teaching Strategies Gold (2011) system to track student progress.

In addition to the programs standards above, CLC provides an enriching social–emotional curriculum, which includes, among other things, teaching emotional literacy through the Yale RULER curriculum at all sites. RULER stands for the five learnable skills of emotional intelligence: Recognizing, Understanding, Labeling, Expressing, and Regulating emotion. The RULER program aims to create a “positive emotional climate,” thereby enhancing academic performance, social skills, leadership skills, and attention, coupled with decreased anxiety, depression, rates of bullying, teacher burnout, and teacher negativity.

Classroom activities vary by age and ability, and classroom structure varies by program. Each classroom has a maximum 10:1 student to teacher ratio, with one head teacher and one or two assistant teachers. Students receive breakfast, lunch, and a snack each day. Most CLC students enroll in the full-day program; a smaller percentage attend the half-day program.

Group FNI for Preschool

In addition to the standard CLC curriculum, children assigned to the intervention group participated in Group FNI-Preschool sessions. These sessions occurred in a single room at three CLC sites. Rooms accommodated at least eight dyads and two nurture specialists (NSs) who are case licensed clinical social workers. Participants sat on a carpeted floor of a classroom, conference room, or special education service room, nestled against large pillows. To limit distractions from mother–child interrelating, the room contained no toys or other attention-grabbing objects. Children sat on the laps of their mothers, face-to-face.

Each FNI session consisted of one or more calming cycles between mother and child, brief motivational discussion on behavior and parenting, and planning for continued calming cycles at home. Support from other participants and NSs was a key feature during maternal group discussion. Visual tools helped participants understand the intervention goals and theory.

A typical session began with introductions of mothers and children to each other if new members were joining. Mothers typically discussed their goals for the session and offered a brief report on the progress of home calming cycles. Then the calming cycles began. A calming cycle consisted of mothers and their children cycling through: (1) separate distress, (2) mutually shared distress, (3) mutual resolution of distress, and (4) mutual calm (i.e., eye contact, pleasurable feelings and calm).

Baseline Assessment: Initial Meeting

Parents arrived with their child for their baseline assessment. NSP staff explained that they will measure the impact of Group FNI-Preschool at the present baseline assessment and at three time points: (1) at baseline; (2) immediately following the last group session, and (3) approximately 2 months following the end of the last group session.

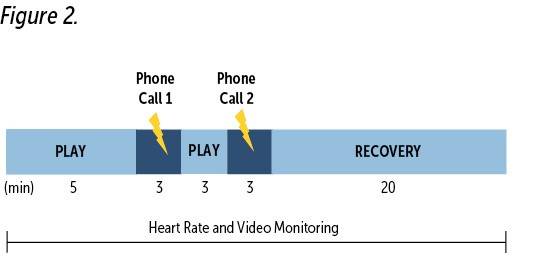

After signing a consent form, the research staff connect physiological monitoring equipment to the child and to the mother. Then, mothers and children perform the Welch-Hane Double-Interrupted Lap Check (see Figure 2), a 34-minute face-to-face interaction with two 3-minute interruptions. This paradigm, which is a variation on the Still-Face Experiment (Tronick et al., 1978), was designed by Welch and Hane specifically for WECS coding. The Still Face Experiment is widely used to test a child’s stress response to brief disruption in the mother’s face-to-face play and communication. The Lap Check is designed to test the child’s stress response and the mother and child’s ability to repair the upset. The double phone call interruption increases the child’s stressful response. The extended 20-minute reunion period tests their ability to repair and provides the NS a later teaching opportunity with the mother.

Figure 2. Welch-Hane Double-Interrupted Lap Check. This experiment is different from the Still Face Experiment in several important ways. First, the Lap Check includes a double interruption, which heightens the child stress response. Second, it calls for an extended 20-minute reunion period, which tests how the dyad recovers from the stressful event.

The Lap Check paradigm consists of 5 minutes of play, followed by an interrupting 3-minute phone call, followed by 3 more minutes of play, followed by another 3-minute phone call interruption, followed by a 20-minute “repair” period. During the phone calls, mothers answer questions from the Parenting Stress Index, Fourth Edition-Short Form (Abidin, 2012; Barroso et al., 2016) read over the phone by study staff. The Lap Test paradigm is singular in that it does not involve toys or joint attention objects to test mother–child interaction. The paradigm involves only close face-to-face communication with the child sitting on the mother’s lap in order to test the pair’s behavioral and autonomic responses.

Following the Lap Check, mothers conduct the Clean-Up Paradigm developed by Kochanska and colleagues (1995). Mothers and children play together with distributed toys until a researcher instructs the mother to ask her child to clean up. Both the Lap Check and Clean-Up paradigms involve physiological measures. The mothers and children attend eight sessions within a 16-week period, when possible.

Beginning Calming Session

On the morning of the first group session, mothers sit with their child on beanbags arranged on a heavy carpet rolled over the floor of a staff meeting room. The NSs give a brief overview of emotional expression, which requires that mothers and their children sit together face-to-face. They explain that the goal of each calming session is to process one another’s deep emotions until they both reach a shared state of calm and want to stay close to one another. Each mother places her child in her lap, looking at each other face-to-face. This sequence prompts an observable behavioral and a measurable physiological response in the mother and the child. The NS explains that their child’s upset reflects a dysregulated autonomic state. Instead of using standard methods aimed at getting the child to self-regulate, such as punishment, threats, or physical means, the NS explains to the mother that the child’s upset is a “call for calming.”

The NS encourages each mother to keep trying to connect until she and the child feel calmed down. This calming typically occurs in about 10 to 20 minutes, depending on the depth of disconnect and upset. One to three upset/calming cycles may occur in each session, often with a period of the child moving away from the mother as an expression of upset. The level of emotional intensity of the sessions is often a reflection of home life. After calming cycles, mothers may reflect on the circumstances of their lives that make it difficult to spend one-on-one time with their child, such as other children and work demands. At these times, the NS will help the mother and child think of ways to find the time to stay emotionally connected and prevent emotional disruptions.

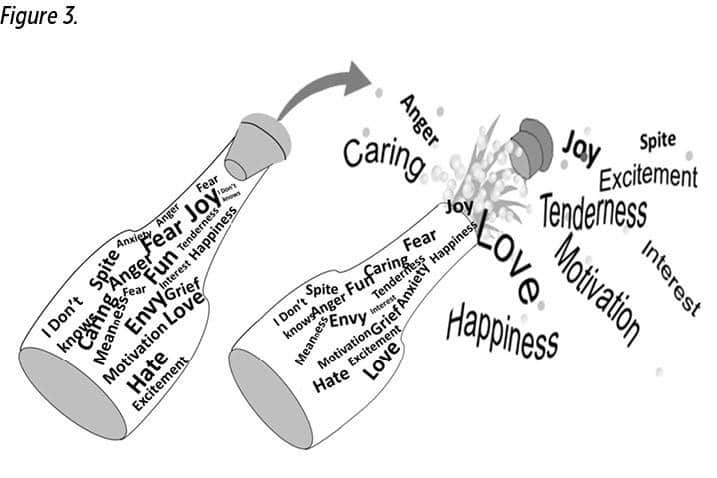

The Emotional Breakthrough

The NSs look for a mother–child emotional “breakthrough.” The emotional conflicts that build up between a parent and child can result in emotional blocks, where the parent, child, or both are resistant to emotional closeness. Fear, anger and blocked feelings can act like a cork, preventing the expression of both positive and negative feelings (see Figure 3). The NS explains that opposition is a sign of autonomic dysregulation, and that emotional expression and connection can sometimes eliminate the need for or take the place of “discipline.”

Figure 3. Schema of bottled-up feelings. Mothers found this metaphor helpful in understanding the idea that holding back emotions from the child is blocking emotional connection. Once the mother or child release and express their emotions, whatever they are, the easier it is for the pair to emotionally connect.

Breakthroughs were unpredictable in the group sessions. Sometimes, a mother–child pair quickly mastered the calming cycle tool. In other cases, a mother–child pair were stuck in a recurring cycle of dysregulation. In the latter cases, a breakthrough can be particularly dramatic.

For example, in a later session, a mother let go of bottled-up feelings. In this case, in response to the child’s consistent resistance and upset, the whole group encouraged the mother to express her emotions. Finally, the mother cried, and the child immediately—and for the first time—responded to her mother’s requests for connection. Their feelings flowed out and together they reached mutual calm. This breakthrough event proved to be extremely cathartic for mother and child. The mother opened up about how various relatives had raised her, and many disciplined her for the smallest infractions. She mentioned experiencing abuse. The mother was able to share with staff things about her own life that she was unable to share with anyone before the breakthrough. She also reported surprise at changes in behavior at home, such as her child asking for “mama bear and baby bear hugs.”

End of Each session: Teaching and Reflections

At the end of the session, mothers discuss their connection successes and failures with the group. This modeling is a strength of group sessions. When a struggling mother sees other mother–child pairs persist through upset to reach calm, it reinforces that emotional connection is achievable and strengthens her resolve to reach the same point with her child.

Mothers feel more capable of placing limits on their child’s behavior after achieving emotional connection for the first time. Learning to say “no” effectively to children can at first cause significant resistance. As mothers and children become connected, calming cycles become faster and smoother and pairs may move through many progressively less intense cycles in a given session. Once a pair is connected and co-regulating, a “no” is more readily accepted—or not needed, as children begin to check with mom before action.

Feasibility of Making Emotional Preparation Part of CLC Standard Curriculum

During the preparation and implementation of this study, CLC and NSP have learned more about how their goals align. CLC’s mission is to “provide comprehensive, high-quality early childhood education and care programs for all families" link. NSP’s is to “develop, test, and scale nurture-based strategies, rooted in rigorous scientific research on emotional connection and co-regulation, to help families everywhere use the healing power of nurture to address and prevent emotional, behavioral, and developmental difficulties” link. NSP, like CLC, aims to help all families. CLC is a primary provider, while NSP is the relational health expert. The NSP needs CLC’s ties to the community and to state political and educational leaders and its large population of more than 1,000 families to test the efficacy and effectiveness of our Group FNI-Preschool model. In the process, NSP is expanding and deepening the “comprehensive, high quality” offerings at CLC.

What is especially promising about the NSP-CLC partnership is the speed at which it solidified. Following a small-scale pilot study at one CLC site, the study quickly expanded to all three CLC programs covering eight sites around Stamford, Connecticut. Directors who listened to NSP’s principal investigator speak about the scientific underpinnings and effectiveness of FNI-NICU and FNI-Preschool in spring 2018 quickly understood the value of our partnership. Teachers who listened to a similar presentation were also excited, but they wanted more information. Why did NSP need to take their children out of class for 2 hours? Because teachers are blind to group assignment in the RCT, the study team could not disclose specific details of the study.

The emotional conflicts that build up between a parent and child can result in emotional blocks, where the parent and/or child is resistant to emotional closeness.

Photo: Vaillery/shutterstock

In smaller meetings, the NSP team explained the study and reiterated details of teachers’ participation. Teachers became more comfortable with NSP presence and the questionnaire due at three time points. The NSP team was readily available to answer questions. Some wrote questions in the margins of forms. The team channeled responses through education coordinators or placed handwritten notes in their mailboxes, and collected a handful of referrals from teachers, most often for struggling students who could benefit from extra help. The study team interpreted this open line of communication as a sign of our strengthening partnership.

Why Helping Parents and Children Stay Emotionally Connected Is Promising

Single mothers, dual-working families, extended days or early participation in out-of-home care, and the use of technology in households have all increased the stress on young children. The rise in socioemotional disorders and the rise in numbers of children under 5 years old who are attending school and child care programs is an important correlation (Walker & MacPhee, 2011). The results of modern American social policy are clear. Many American families have not adapted well to the stress caused by physical and emotional separation.

A strength of the group FNI-Preschool method is that it is experiential, communal, and does not rely on didactic educational material or training. Mothers immediately engage with their child in the first session and learn that when they reach a level of calm with their child, and reconnect at an autonomic emotional level, symptomatic behavior disappears. This makes the activity very rewarding and reinforcing for both mother and child.

Learn More

Nurture Science Program

Website: www.nurturescienceprogram.org

Phone: 212-342-4400

Email: nurturesceince@cumc.columbia.edu

Newsletter: https://mailchi.mp/cumc/subscribeChildrens

Learning Centers

Website: www.clcfc.org

Phone: 203-323-5944

Email: stefaniehorn@clcstamford.org

The group method also functions as a support group, which is especially helpful for single parents, who may not have support at home. Through the group calming sessions, mothers can participate in their child’s preschool in a constructive way. NSs portray behavioral problems as common, predictable, and easily resolved through the calming cycle, thus destigmatizing and normalizing dysregulated behavior. This distinction makes this approach very different from most current solutions to classroom disruptive behavior, which involve remedies such as “time-out” punishments, which preclude forming a co-regulatory relationship with the teacher

Future studies will test whether including family members is helpful in engaging key family members in the calming cycle strategy within the home.

Photo: Monkey Business Images/shutterstock

Fathers and grandparents did not attend the sessions in this study. However, future studies will test whether including family members is helpful in engaging key family members in the calming cycle strategy within the home. No participating children were primarily raised by a family member other than the biological mother. Future studies will include the primary parent, whoever this may be.

Conclusion

At the time of this writing, NSP together with its community partner, CLC, has completed the intervention phase of the RCT and is in the data analysis phase. We will soon know whether the data from this RCT uphold efficacy hypotheses. The model has proven both feasible and popular with families and CLC staff. Plans are underway to conduct a follow-up effectiveness trial, in which preparing parents and children emotionally for the preschool experience will be included as part of the CLC standard programming in the upcoming school year. All incoming families attend one single and one follow-up group calming session. Due to COVID-19, the initial calming session occurred via videoconference. CLC and the NSP have plans to test an on-going “Drop-In” center, where mothers and children can practice calming cycles with the help of CLC staff, either in person or via videochat.

Suggested Citation

Welch, M. G., Markowitz, E. S., & Jaffe, M. E. (2021). Facilitating parent–child emotional preparation to improve classroom behavior in a community-based early education program. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 41(Supp.).

Authors

Martha G. Welch, MD, DFAPA, is the director of the Nurture Science Program in Pediatrics at Columbia University Irving Medical Center and associate professor of psychiatry in pediatrics and pathology and cell biology at Columbia. Dr. Welch has been a pioneer in the treatment of emotional, behavioral, and developmental disorders for more than 40 years. Decades of clinical observations led her to create a new paradigm that employs the primacy of co-regulatory vs. self-regulatory processes in optimal child development. Dr. Welch leads a multidisciplinary team of researchers in testing Family Nurture Intervention and exploring the underlying biological phenomenon of emotional connection. She has published more than 40 peer-reviewed articles and is a diplomate of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology and a distinguished fellow of the American Psychiatric Association.

Elizabeth Markowitz, MSc, is a research coordinator for the Nurture Science Program (NSP) at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Ms. Markowitz manages preschool-aged studies in Connecticut. She designed and executed a qualitative component for NSP’s randomized controlled trial in collaboration with Children’s Learning Centers of Fairfield County. Before NSP, she earned her master’s of science degree in medical anthropology from University College London with a focus on Latin American maternal health. She continues to be especially interested in cross-cultural experiences of health in under-resourced populations.

Marc E. Jaffe, JD, is the CEO of Children’s Learning Centers of Fairfield County (CLC). CLC is the largest nonprofit early education program in southwest Connecticut, serving about 1,500 children and families per year. In a partnership with Yale University’s Center for Emotional Intelligence, CLC conducted a study of the Ruler Program for Pre-K children and effectively implemented the program at CLC. Mr. Jaffe has served on the boards of many community and education organizations including Harlem RBI (Dream) and Stamford Cradle to Career. Prior to CLC, Mr. Jaffe was a media, technology, and publishing executive having senior management roles at Simon & Schuster and Rodale Press among others. He is a graduate of Columbia College and Columbia University School of Law.

References

Abidin, R. R. (2012). Parenting Stress Index (4th ed., PSI-4). P. A. Resources Ed.

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA Preschool forms and profiles. University of Vermont, Department of Psychology.

Austin, J., Curren, L. C., Ludwig, R. J., Hane, A. A., Myers, M. M., & Welch, M. G. (2021). Development of the mother’s socioemotional support circle: A novel scale to assess mother’s perceived socioemotional support [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Nurture Science Program, Department of Pediatrics, Columbia University Irving Medical Center of New York City.

Barroso, N. E., Hungerford, G. M., Garcia, D., Graziano, P. A., & Bagner, D. M. (2016). Psychometric properties of the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF) in a high-risk sample of mothers and their infants. Psychological Assessment, 28(10), 1331–1335. link

Connecticut Office of Early Childhood. (2020a). Connecticut early learning and development standards. link

Connecticut Office of Early Childhood. (2020b). Connecticut preschool and assessment framework. link

Croft, S., Stride, C., Maughan, B., & Rowe, R. (2015). Validity of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire in preschool-aged children. Pediatrics, 135(5), e1210–1219. link

Goodman, A., & Goodman, R. (2009). Strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a dimensional measure of child mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(4), 400–403. link

Griffin, D. W., & Bartholomew, K. (1994). The metaphysics of measurement: The case of adult attachment. Advances in Personal Relationships, 5, 17–52.

Hane, A. A., LaCoursiere, J. N., Mitsuyama, M., Wieman, S., Ludwig, R. J., Kwon, K. Y., … Welch, M. G. (2019). The Welch Emotional Connection Screen: Validation of a brief mother-infant relational health screen. Acta Paediatrica, 108(4), 615–625. link

Head Start. (2020). Head Start child development and early learning framework. link

Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K. A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., Jones, L., &. Dunne, M. P. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health, 2(8), e356–e366. link30118-4)

Kochanska, G., Aksan, N., & Koenig, A. L. (1995). A longitudinal study of the roots of preschoolers’ conscience: Committed compliance and emerging internalization. Child Development, 66(6), 1752–1769. link

Ludwig, R. J., & Welch, M. G. (2019). Darwin’s other dilemmas and the theoretical roots of emotional connection. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 683. link

Porges, S. W., Davila, M. I., Lewis, G. F., Kolacz, J., Okonmah-Obazee, S., Hane, A. A., Kwon, K. Y., Ludwig, R. J., Myers, M. M., & Welch, M. G. (2019). Autonomic regulation of preterm infants is enhanced by Family Nurture Intervention. Developmental Psychobiology, 61(6), 942–952. link

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

Rivers, S. E., Brackett, M. A., Reyes, M. R., Elbertson, N. A., & Salovey, P. (2013). Improving the social and emotional climate of classrooms: a clustered randomized controlled trial testing the RULER Approach. Prevention Science, 14(1), 77–87. link

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, R., Vagg, P. R., & Jacobs, G. A. (1983). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press.

Teaching Strategies Gold, Inc. (2011). Teaching Strategies Gold: Fast facts for decision-makers. link

Tronick, E., Als, H., Adamson, L., Wise, S., & Brazelton, T. B. (1978). The infant’s response to entrapment between contradictory messages in face-to-face interaction. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 17(1), 1–13. link

Walker, A. K., & MacPhee, D. (2011). How home gets to school: Parental control strategies predict children’s school readiness. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 26(3), 355–364.

Welch, M. G. (2016). Calming cycle theory: The role of visceral/autonomic learning in early mother and infant/child behavior and development. Acta Paediatrica, 105, 1266–1274. link

Welch, M. G., & Ludwig, R. J. (2017a). Calming cycle theory and the co-regulation of oxytocin. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 45(4), 519–540. link

Welch, M. G., & Ludwig, R. J. (2017b). Mother/infant emotional communication through the lens of visceral/autonomic learning and calming cycle theory. In M. Filippa, P. Kuhn, & B. Westrup (Eds.), Early vocal contact and preterm infant brain development: Bridging the gaps between research and practice. Springer International.

Welch, M. G., & Myers, M. M. (2016). Advances in family-based interventions in the neonatal ICU. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 28(2), 163–169. link