Barbara Jessing, Fontenelle House, Omaha, Nebraska

Jennie Cole-Mossman, JBS International Consulting, North Bethesda, Maryland

Abstract

Young children in the child welfare system are inherently vulnerable to disruptions in early attachment, and abrupt changes of placement can function as trauma triggers. In this article, the authors present a case from a Child–Parent Psychotherapy (CPP) Learning Collaborative which exemplifies the potential trauma of placement changes, and how CPP is uniquely suited to support children and caregivers before, during, and after a placement change. They examine the elements needed at each stage of CPP—foundation, core intervention, and termination—to promote a healthy transition. Concurrent attention to the facilitating attuned interaction (FAN) model of reflective practice is a tool to help CPP practitioners navigate the difficult emotional experiences involved in these transitions.

In the pressured environment of child welfare, it is too common for the adults involved to dismiss the emotional experience of a young child. A judge orders a change in foster placement, which the child’s therapist and other team members learn about after the fact. A child goes home after 18 months with a foster family to a parent he has visited on only a few occasions, with no opportunity to prepare for this change with the help of his therapist. A caseworker decides not to refer a child for therapy when he or she enters foster care. In the aftermath of such actions, it is often unclear whether therapy will continue, with whom, and why. Therapists can experience secondary trauma when these abrupt changes occur. These are moments of emotional challenge as they see their small clients in distress.

The science of early adversity shows that dependable, supportive caregivers are the most important buffer of a young child’s stress, with the capability to transform toxic into tolerable stress (Harvard Center on the Developing Child, n.d.). Child–parent psychotherapy (CPP), an evidence-based practice for children birth to 5 years old, offers a flexible therapeutic framework to support caregivers and young children before, during, and after transitions in placement. The therapist can bring the unique lens of CPP to focus on case planning and decision making, with the goal of a healthy and supported transition (California Evidence Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare, n.d.). Essential to the fidelity of CPP is reflective practice. The FAN (facilitating attuned interaction; Gilkerson & Imberger, 2016) model is both a conceptual tool and a set of skills that assist with reflective consultation. Its roots in early childhood mental health make it uniquely suited to CPP practice.

CPP Learning Collaborative

Building on work on triadic formulation in CPP, which is the therapeutic work that occurs between the child and more than one caregiver or parent, (McHale, Fivaz-Depeursinge, Dickstein, Robertson, & Daley, 2008; McHale, Salman, Strozier, & Cecil, 2013), the CPP Learning Collaborative trainers developed a learning experience to help trainees navigate these transitions.

Inevitably, multiple caregivers and systems are involved in the child’s life, and it is challenging to orchestrate the “Who, What, When, Where, and Why” of CPP. The foundation stage of CPP culminates in a clear clinical formulation which guides the intervention stage. In CPP, therapists, serving as conduits between child and caregivers, narrate the child’s experience. They identify the necessary participants, expand the focus of assessment and treatment, establish common goals among caregivers, find new ports of entry, and develop interventions specific to grief, loss, adaptation, and change.

In this article we present a conceptual model for implementing CPP to support children through placement changes. Our model is organized around the three critical stages: foundation, core intervention, and termination. For each stage, we identify critical elements for success and note potential pitfalls. We discuss the use of the FAN as a transformational model for reflective practice. The FAN model was designed to bring the principles of reflective practice to early childhood settings. Provided in individual or group consultation sessions, reflective consultation helps therapists recognize their own emotional reactions to events in a case, recognize the need to self-regulate, and engage in productive problem solving. The flexibility of CPP is a mixed blessing for new learners, who sometimes long to be told what to do. Reflective practice is one of the key elements of CPP fidelity. It helps to activate therapists’ “in the moment” capacity to recognize and scaffold on small windows of opportunity.

The Story Begins

In a CPP Learning Collaborative meeting, a trainee presented a case that first broke our hearts, and then challenged us to find solutions. The case we present is substantially hers, though we have changed some details. Because we found that more than half of our CPP cases raised these same issues of multiple caregivers and transitions, this story also reflects learning derived from similar cases.

In a courtroom in rural Nebraska, a child’s future was on the line. Three-year-old David had lived with his foster/adoptive parents since he was 6 months old. The details of his first months are few. His mother was known to have a drug addiction. He had come into Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) care because of severe neglect. He had poor eye contact; did not cry, even when he needed to be changed, comforted, or fed; and resisted being touched or held. He showed significantly regressed speech and motor activity during the time he had visits with his mother, but by the time he was 2 years old, parenting time dwindled to none.

With his biological mother missing, the foster parents offered permanency. When the final hearing on termination of parental rights approached, the foster mother told the therapist that she had finally let go of the last hesitation— “what if” he goes back to mom—and fully gave over her heart to David. And then the child’s biological father entered the court room. A search by DHHS had identified him, and paternity was confirmed. He had only a one-time encounter with the child’s mother and had not known that he had a child. He made it known to the court that he wished to intervene. The foster parents were shocked and devastated, as was the therapist. Now the therapist was being asked to make recommendations for a transition plan for David and his biological father.

Our trainees show distress and confusion as they navigate the challenges of serving children in the child welfare system. How does a therapist, attuned to a fragile child and his first tenuous attachment figure, cope with the prospect of a disruption that could set him back? As the court addressed the issues of the father’s rights, and the best interests of the child, what would the therapist have to say? These questions are addressed not only thinking of the procedures of CPP, but also in reflective consultation using the FAN. The feelings of distress and confusion must be addressed to ensure clearheaded thinking about the proper analysis and intervention necessary to treat the child and the relationship with the caregivers.

While asserting the father’s standing in the case, the court allowed for time to assess his skills and readiness to parent the child. The father agreed to participate in services to ease the transition. The foster mother looked to the therapist to be an advocate for maintaining the plan for adoption and was heartbroken when it became clear that the court was proceeding to permanently place the child with his biological father.

Before therapy could resume, the therapist needed to resolve her feelings about the sudden changes. Here is the first point in this case where the FAN model was applied in consultation. The therapist needed to explore those feelings, so they did not interfere with her work with both the dyads. Understanding one’s own feelings and motivations is essential when dealing with transitions that are often sudden and seem unfair to one of the parties.

The Foundation Stage

The foundation stage is the initial period when the therapist meets all the significant parties involved in the child’s care and begins to understand the child’s needs and challenges within the context of the family or caregiving situation.

David initially entered treatment for his anxiety. He had difficulty separating from his foster mother and frequently sought her out as a “safe base.” He showed anxiety and aggression when new people, such as the therapist, became involved. He had difficulty initiating sleep and had frequent night waking.

His father’s entry into David’s life required extended time in the foundation phase. This began with an interview to assess his needs as a single parent, learn about his hopes for his son, identify therapy outcomes, and begin building a therapeutic relationship. A Crowell procedure, which is a structured series of observations of parent–child interaction (Zeanah, 2000), was conducted to observe his interactions with David, and to understand from David’s perspective what this new person in his life meant. The questions that had to be raised as the foundation phase concluded were: Is CPP with this parent the appropriate course of action? Are there any safety concerns? Is the parent willing to engage? Is there a mutually agreeable outcome of therapy? The conclusion reached was that CPP would expand to include David’s father, with the eventual goal of reunifying with David.

We knew that a critical issue for David would be the support of his foster mother as he began to develop a relationship with his biological father. What level of cooperation could we expect between the caregivers? To be effective, the therapist had to use reflective consultation to consider her own feelings and biases that emerged. She had to understand the needs of both the father and the foster parent, as she hoped they could prioritize a healthy adjustment for David. This was another time point in the case where reflective consultation allowed her to examine and regulate her feelings before formulating a clear path forward for CPP. She was able to use reflective consultation to determine what the real issues were in this case, and to disengage from any preconceived notions she had previously about what this family context should look like.

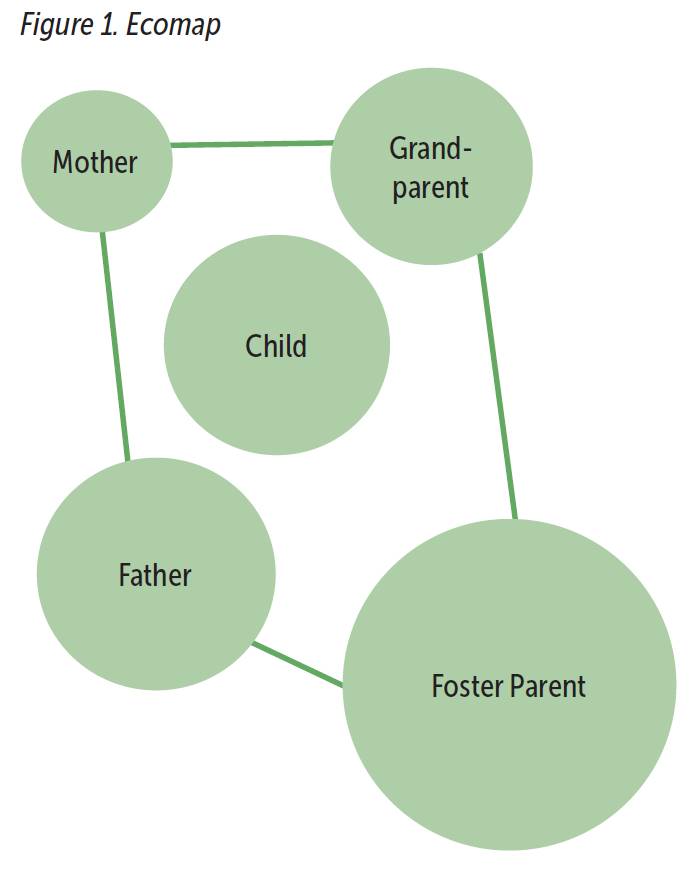

As we reviewed the case with the trainees, we constructed an ecomap (see Figure 1). This technique was so helpful that we now encourage them to use it in all cases. With the child at the center, the ecomap shows every significant caregiver—past or present, biological and foster parents, grandparents, and others. We documented the relationship between David and each caregiver, including his biological mother—although gone, she had left an impression. As he grows, he will need an understanding of who she was and why she could not care for him so that she does not become his “ghost in the nursery” (Karr-Morse, Felitti, & Wiley, 2013). In addition, we documented relationships among the caregivers. There was considerable hostility toward the absent mother—and between David’s foster mother and biological father. She did not want to be the one who made it easier for David’s father to parent him. David’s father, on the other hand, was somewhat dismissive of the effects of separation. His own parents had divorced, and he had lost custody of other children. Disruption was familiar to him, but his attitude was that people just get over it. He believed that David would, too.

Photo: szefei/shutterstock

We know from literature on marital conflict and co-parenting that the better the cooperation among caregivers, the better for the child (Davies & Cummings, 1994). Conversely, ongoing hostility is readily perceived by the child and impedes adjustment. More experiences with conflict predict more negative emotions and greater behavioral reactivity in response to conflict. These effects result in a reduced capacity to handle emotions due to repeated exposure and feelings of emotional insecurity.

What could we expect in David’s case? The father had no strong feelings about the foster parents, although he knew that they saw him as a disruptor. The foster mother struggled with any contact or interaction with David’s father. As the first session with David and his father was scheduled, the foster mother even questioned if she could transport him. Eventually, she recognized that it was best for David to have the support of someone he loved and trusted. The therapist was there to offer support to the foster mother so that, in turn, she could support David.

David and his father met for the first time in the therapist’s office. Video shows a child tentatively moving from his foster mother’s side. She gradually increased her distance from him.

She encouraged him to throw a ball to his father, their very first interaction. David’s father waited with patience. David was anxious throughout most of the session, avoiding eye contact; but warmed up as the session proceeded. As the foster mother buckled him into his car seat for the ride home, David struck at her aggressively. She expressed her concerns to the therapist that contact with his father would result in behavioral regression, as she had seen after visits with his biological mother.

Where could we find some common ground between these caregivers? It was a very small island found in the transitions of each session. The foster mother would bring David, reassuring him that he was safe; and return to pick him up. It was too difficult for her to have any direct contact or conversation with the father; so the therapist served as conduit between the caregivers. David’s father did not have insight into the importance of the foster parents in David’s life. But he was willing to engage in therapy, and the CPP therapist had the opportunity to help him understand why the foster mother mattered to David.

The therapist felt that each of the caregivers seemed able to put David’s needs ahead of their own. She had worked hard during reflective consultation to understand and work through her feelings. She struggled with some of the same feelings that both the father and foster mother were experiencing. But it was her task to contain those feelings in order to support what was best for David.

Core Intervention Stage

The core intervention phase is the active work of CPP—which was just beginning as our trainee presented this case. It proceeded with the primary focus being on David and his biological father, and only somewhat indirectly with the foster mother. This flexible approach to offer concrete and emotional support to the foster mother so she could be there for David is what makes CPP a good fit for difficult situations such as these.

A treatment plan, initially focused on reducing David’s anxiety and strengthening his attachment, was still appropriate—but now focused on his father as the primary caregiver. The most significant addition to treatment was to continue to build on the caregivers’ mutual care, concern, and love of David. That meant opening the father’s eyes to what the foster parents had done to nurture his son, helping the foster mother manage the grief of David leaving their home, and accepting his father’s new role in his life. As treatment proceeded, the CPP therapist recognized the need to refer the foster mother to another therapist for grief work. The therapist must not take personally the feelings of the foster parent but needs to be able to support her. In doing so, she modeled for the foster mother what she in turn gave David. Reflective consultation again supports the therapist in processing and regulating her own feelings so she can help the other parties do this in parallel process.

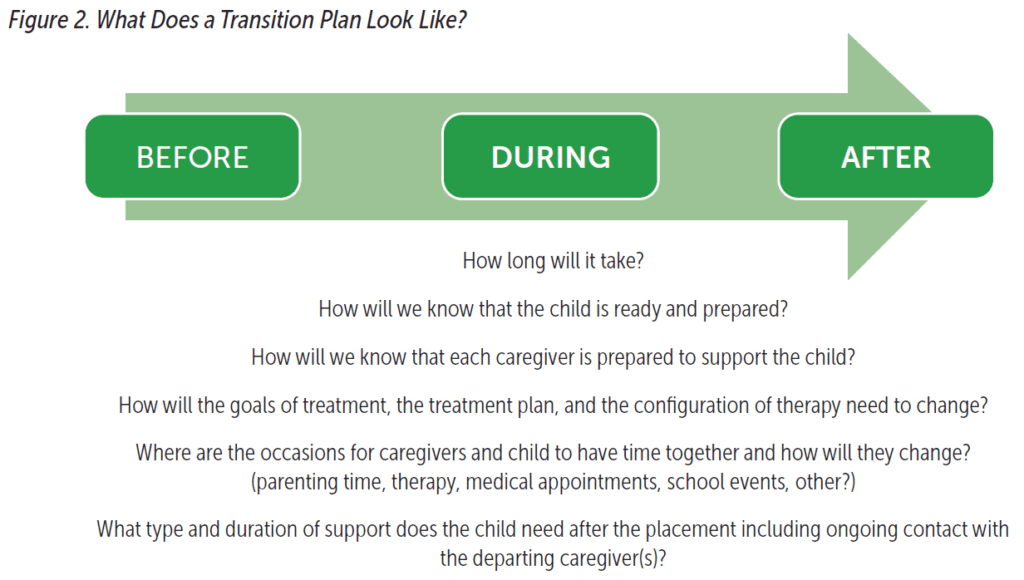

The treatment plan also needed to incorporate the DHHS requested transition planning. We are often asked this question: “How long will it take?” But we reframe that as: “What needs to happen, in what sequence, and with what behavioral road markers?” (see Figure 2). Sometimes we have no choice— the transition has happened or is imminent. That could have happened here—David’s father could have refused to participate in CPP. But the therapist in this case was able to join with the father, help him see the benefits of a gradual transition for his son, and gain his voluntary cooperation in the process.

The core intervention stage had a duration of about 6 months, with weekly or biweekly sessions. David’s father regularly drove a 3-hour round trip to attend sessions. Parenting time gradually increased, and eventually included overnight stays. The first few visits were at a motel in the same town where David lived with his foster parents, to reduce disruption for him and calm some of the anxieties he and his foster parents might feel. Eventually, there were weekends in the father’s home.

We encouraged the therapist to observe progress toward treatment goals—signs of David feeling safer and more connected with his father; monitoring any behavioral regression and helping both caregivers to respond appropriately if it happened; and, for the father, a better understanding of his child’s attachment needs and style as well as his own responsiveness.

CPP offers many opportunities for children to grapple with the changes in their lives. Every session has a hello and a goodbye. For David, every session meant that he walked from his foster mother’s side to his father, and back again at the end. These were rehearsals for his eventual goodbye to the family who had nurtured him through his first 3 years. The CPP therapist searched for clues in David’s play, interactions with caregivers, and reactions to transitions to implement interventions that helped him make sense of what was happening, and to help attune his caregivers to his needs.

Provided in individual or group consultation sessions, reflective consultation helps therapists recognize their own emotional reactions to events in a case, recognize the need to self-regulate; and engage in productive problem solving. Photo: pixelheadphoto digitalskillet/shutterstock

Termination Stage

It is the best possible scenario for CPP to begin before the transition, remain available throughout, and continue as needed for a period of time after the transition. For all parties, termination of therapy is difficult. The therapist is left wondering if the work is done, the child and the caregivers are often letting go of a significant relationship, and all are left to wonder about what will happen in the future.

The therapist had hoped it might be possible for David to continue to see his foster parents after reunifying with his father. But the emotional difficulty the foster parents had with the loss was just too much. In addition, the distance to the new home made it impossible for the therapist to continue to see David and his father. There was no CPP therapist any closer to David’s new home, but a referral was found to another child therapist who would be there to support his adjustment. The therapist, in parallel process, is letting go of a family while being unsure of the stability of the relationship. The foster parents and David must also let go of a relationship. And David’s father continues a new relationship, but without the support of the therapy that brought him and his child together.

Using the FAN as the model for reflective consultation helped the therapist identify where each person was in their processing of events, including how the therapist herself was feeling. The foster parent and father both began sessions deeply in their emotions. The clinician must offer empathic inquiry and validation of the difficulty of the situation. Upon further regulation of these emotions, the therapist and the caregiver could explore the internal world of the child and the child’s emotional state. This is a place where the clinician could help the foster mother and parent join, even if not in the same room, around the idea of helping to provide emotional comfort and continuity for David. The clinician had the difficult task of building the capacities of each of the caregivers to provide the child with what he needed, despite each being uncomfortable with the process and the outcome. The clinician was able to develop this new caregiver alliance even though the caregivers were not present together in order to give the child a smoother transition and a healthy memory of the love and care he received from the foster parent.

Conclusion and Lessons Learned

Child–parent psychotherapy is an effective modality for supporting young children and caregivers through difficult transitions with implications for attachment. Photo: Serge Vo/shutterstock

CPP is an effective modality for supporting young children and caregivers through difficult transitions with implications for attachment. CPP therapists are uniquely qualified to advise child welfare professionals on transition planning that supports young children, and they have a solid foundation for their contributions.

Forging better relationships among caregivers can ease transitions for young children. Adapting each stage of CPP therapy to ease transitions, in combination with the FAN as a framework for reflective consultation, allows the clinician to be the conduit for fostering new attachment and emotionally responsive parenting by the biological parent, while honoring the child’s emotional experience and giving space to an important and formative relationship with the foster parent. Widening the CPP lens to consider all caregivers in the child’s life, including the quality of the relationships among the caregivers, is critical to a good transition. The FAN also conveys support to the CPP practitioner at emotionally challenging moments in treatment.

Learn More

Facilitating Attuned Interaction Model of Reflective Practice The Erickson Institute

Child–Parent Psychotherapy

Don’t Hit My Mommy!: A Manual for Child–Parent Psychotherapy With Young Children Exposed to Violence and Other Trauma

A. F. Lieberman, P. Van Horn, & C. G. Ippen (2015) Washington, DC: ZERO TO THREE www.childparentpsychotherapy.com

Early Childhood Innovations in Nebraska

www.nebraskababies.com

Author Bios

Barbara Jessing, MS, obtained a master’s degree in counseling from the University of Nebraska at Omaha, and a certificate in marriage and family therapy from the Karl Menninger School of Psychiatry in Topeka, Kansas. She is a licensed mental health practitioner and certified marriage and family therapist in Nebraska. She has more than 36 years of experience with community mental health and child welfare services, with a specialization in the treatment of child trauma. She provided clinical leadership in the development of innovative treatment programs for child and family healing and recovery. She is currently a consultant and trainer at Fontenelle House in Omaha, Nebraska. She is an endorsed child–parent psychotherapy trainer.

Jennie Cole-Mossman, MA, obtained a master’s degree in marriage, family, and child counseling from the University of Southern California. She is a licensed independent mental health practitioner in Nebraska. Ms. Cole-Mossman currently works as a technical expert lead for JBS International Consulting. Her current work is supporting the grantees for the Office of Victims of Crime: Enhancing Community Response to the Opioid Crisis, Serving Our Youngest Crime Victims. Prior to this Ms. Cole-Mossman served as the co-director of the Nebraska Resource Project for Vulnerable Young Children at the University of Nebraska. She is an endorsed child–parent psychotherapy trainer and a trainer for the facilitating attuned interaction model of reflective practice.

Suggested Citation

Jessing, B., & Cole-Mossman, J. (2020). The warmest handoff: Using child–parent psychotherapy to ease placement transitions. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 40(6), 43–48.

References

California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare. (n.d.). https://www.cebc4cw.org

Davies, P. T., & Cummings, M. E. (1994). Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 387–411.

Gilkerson, L., & Imberger, J. (2016). Strengthening reflective capacity in skilled home visitors. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 37(2), 46–53. Harvard Center on the Developing Child. (n.d). A guide to toxic stress. Retrieved from source

Karr-Morse, R., Felitti, V. J., & Wiley, M. S. (2013). Ghosts from the nursery: Tracing the roots of violence. New York, NY: The Atlantic Monthly Press.

McHale, J., Fivaz-Depeursinge, E., Dickstein, S., Robertson, J., & Daley, M.(2008). New evidence for the social embeddedness of infants’ early triangular capacities. Family Process,47(4), 445–463. doi:10.111 1/j.1545-5300.2008.00265.

McHale, J. P., Salman, S., Strozier, A., & Cecil, D. K. (2013). V. Triadic interactions in mother-grandmother coparenting systems following maternal release from jail. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 78(3), 57–74. doi:10.1111/mono.1202.

Zeanah, C. H. (2000). Handbook of infant mental health. New York, NY: Guilford Press.