The Children America Overlooks — and Why My Work Lives Where Their Futures Are Decided

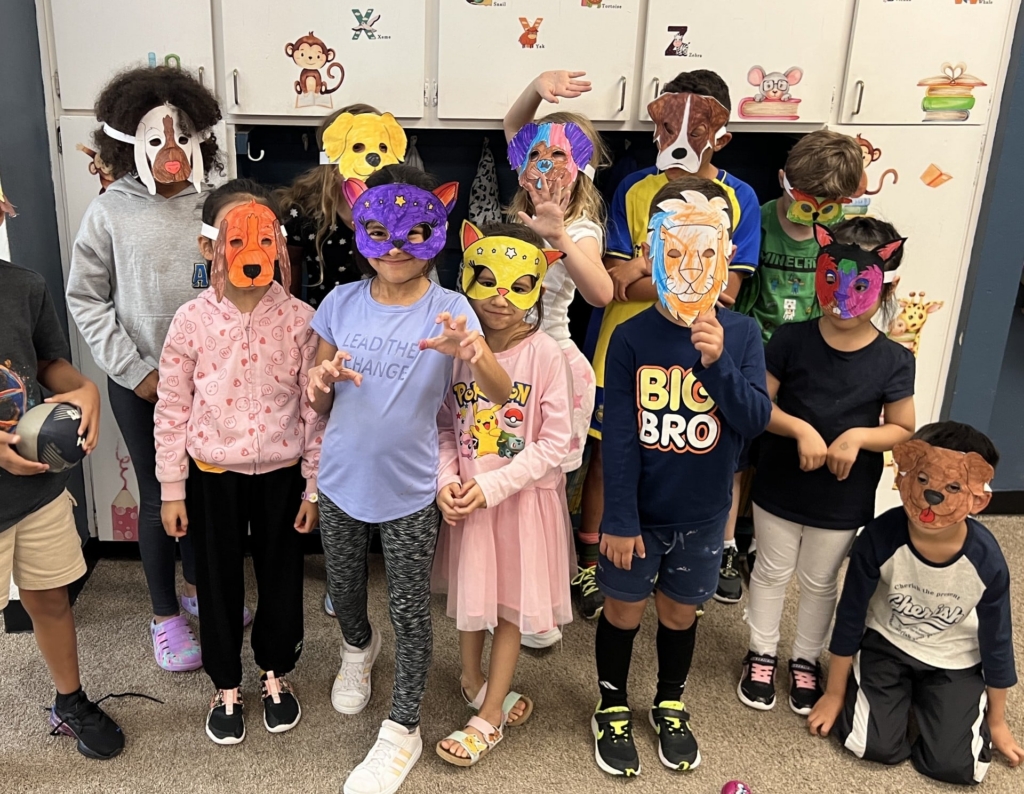

Iryna Liusik is an early childhood educator with a background in linguistics and emotional development. She works at the intersection of language, identity, and emotion, supporting young multilingual learners as they build confidence, expressive language, and emotional regulation. Based in Allen, Texas, Liusik designs trauma-aware, linguistically grounded learning experiences that help children feel safe, capable, and connected across cultures. Her work supports the growing population of multilingual children in the United States by translating research on early bilingual development into practical classroom strategies. She focuses on helping educators understand the emotional and linguistic needs of children navigating more than one language, particularly those who freeze under pressure, lose access to language when overwhelmed, or struggle to find their voice. At Brookhaven Academy, Cranehill Learning Services, Inc., she partners with diverse families to nurture grounded, expressive, and emotionally secure young learners — because language, she believes, is more than speech; it’s belonging.

There is a moment that happens in classrooms that is almost always missed.

A child takes a breath as if to speak, a small inhale that looks like nothing to the adult at the front of the room, and then something inside them closes. Their lips stop moving. Their shoulders stiffen. Their eyes drop to the floor. Most people see hesitation. I’ve learned to recognize a nervous system deciding whether it feels safe enough to exist.

Children don’t walk into “school.” They walk into adults. They walk into our pace, our tone, our body language, our unfinished anxiety from the morning, our attempts to hold ourselves together. They pick up cues we don’t know we’re giving. I’ve had children freeze just because I rushed through a sentence. I’ve seen toddlers scan my face after hearing a loud noise, waiting for me to tell them whether the world is okay. Before they learn to read text, they read us.

And in the America we’re living in today, this emotional reading is happening under conditions most adults forget to consider. Children arrive carrying far more than backpacks. Some bring two languages woven into a single thought. Some bring memories of homes they left behind. Some carry the tension of parents working two jobs, or the quiet fear they overheard at night when adults thought they were asleep. A surprising number carry trauma no one has named yet. And many of them — far more than our systems admit — feel lost between cultures, between languages, between selves.

This is not exceptional anymore. It is the demographic reality of the United States. Yet, our educational structures still envision a very different child: a monolingual child, emotionally uncomplicated, culturally straightforward, and neurologically unburdened. That child rarely walks through the door anymore. And the cost of misunderstanding the real child is growing.

The Nervous System Arrives Before the Child Does

Modern neuroscience has made one thing painfully clear: a child cannot learn if their nervous system is bracing for danger.

The brain can’t stay in learning mode and survival mode at the same time. And for multilingual or immigrant children, the triggers are often invisible to us. A harsh tone. A sudden change in routine. An overwhelmed teacher is trying to hide their stress. A language they don’t yet fully understand is spoken too fast.

I’ve watched English vanish from a child’s mouth simply because fear took over. I’ve watched a child who speaks two languages go completely silent in both when they felt unsafe. I’ve watched a little boy with two cultures inside him cling to the only adult who spoke his home language, not because he needed translation, but because he needed regulation. Adults label these moments as “behavior.” But behavior is almost always biography in disguise.

Language Is Also a Nervous System

Multilingual children do not experience language the way adults think they do.

Their emotional worlds arrive faster than their vocabulary. Sadness may come in one language, but the words to express it may exist in another. A child may freeze not because they are shy, but because translating emotion through two systems under stress feels impossible.

A little girl once whispered something to me in her home language and burst into tears before she could repeat it in English. It wasn’t a language issue. It was safety. She needed to speak her feelings in the language where that feeling lived. We don’t just remove words. We remove their internal anchor. This can break something in them that is hard to put back together.

The differences between multilingual and single-language speakers exist even at the neural level.

Identity Builds Itself Between Languages

A multilingual child builds more than vocabulary; they build themselves.

One identity forms in the language of home, another in the language of school. Sometimes those identities conflict. Sometimes a child feels confident in one and lost in the other. Without guidance, their sense of self fractures quietly.

I’ve seen children light up in their home language and go flat the moment they switch to English. I’ve seen others who work so desperately to “fit” that they abandon the language that holds their childhood memories.

My work is to make sure they don’t have to leave parts of themselves behind just to survive classroom expectations.

Trauma Has Many Accents

Trauma rarely announces itself. It whispers. It hides.

It shows up as sudden silence, as regression, as a child who refuses to enter the room without scanning every corner first. It shows up in the bilingual child who mixes languages in panic, or the child with disabilities whose distress is misread as “noncompliance.”

Trauma has many dialects, and if we don’t know how to listen, we misdiagnose children’s lives. And misdiagnosis becomes misdirection. Misdirection becomes mistrust. Mistrust becomes a future that shrinks instead of expands.

The Adult Nervous System Is the First Curriculum

Children learn calm only from adults who have practiced calm.

They borrow our breathing, our steadiness, our sense of safety. I’ve seen a child’s shoulders drop the moment I softened my voice. I’ve watched a child regulate simply because I slowed my movements. I’ve felt a child’s body relax against mine before they found the words to explain why they were upset.

Co-regulation is not philosophy, it is biology. A regulated adult lowers a child’s cortisol; a dysregulated adult raises it. This is the part the system still doesn’t understand: the adult is the intervention. Yet we expect teachers to be emotional anchors while living inside environments that overwhelm even the strongest among them. You cannot pour stability out of an empty nervous system, but that’s what we ask educators to do every day.

Why This Matters for the United States

The United States is changing faster than its systems can keep up.

Today’s classrooms hold children who speak in the rhythms of many languages, who carry two or three identities inside them, who feel the world intensely, and who are shaped as much by stress as by instruction. Meanwhile, educators are rarely trained in multilingual identity formation, bilingual brain development, trauma neurobiology, co-regulation science, the intersection of disability and trauma, or the cultural realities that shape whether a family asks for help.

When these understandings are missing, children are mislabeled instead of understood, disciplined instead of supported, and pushed into evaluations that do not fit the truths of their lives. The consequences are not abstract. They are academic delays, behavioral challenges, fractured identities, and families who lose trust in the very systems meant to help them. These children are not the outliers, they are the future of the country. If we fail to understand them, we fail to understand the nation they will inherit and shape. My work lives directly inside this gap: the place where America’s demographic reality meets its educational responsibility.

The Core Truth That Shapes Everything I Do

A child’s voice is more than language. It is the beginning of who they will become.

And that beginning depends on adults who can hear not only what the child says, but what the child cannot yet say.

When a child is met by someone who can read the silence behind the behavior, understand the emotional world behind the language, and create the safety their nervous system requires, everything shifts. Learning becomes possible. Identity becomes whole. Resilience becomes real.

This place — where trauma, language, identity, and neuroscience meet — is the exact spot where I work. It is the place where futures quietly turn. And it is the place where the United States needs specialized expertise the most.

Related Resources