Julie Cohen, ZERO TO THREE, Washington, DC

Deborah Roderick Stark, Deborah Roderick Stark and Associates

Jamie Colvard, ZERO TO THREE, Washington, DC

Abstract

This article describes some of the remarkable accomplishments of the states that have participated in the Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Financing Policy Project (IECMH-FPP). The purpose of the IECMH-FPP is to support states’ advancement of IECMH assessment, diagnosis, and treatment policies that will contribute to the healthy development of young children. The policy stories are meant to inspire and offer lessons learned for other states interested in advancing IECMH policy. These stories demonstrate that, despite funding constraints and the challenging political landscape, there are always opportunities to take action to increase access to high-quality mental health services for pregnant women, young children, and families.

ZERO TO THREE launched the Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Financing Policy Project (IECMH-FPP) in 2016, with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Irving Harris Foundation, the Alliance for Early Success, and the University of Minnesota. The purpose was to support states’ advancement of IECMH assessment, diagnosis, and treatment policies that will contribute to the healthy development of young children. The first cohort of states participating in the IECMH-FPP included Alaska, Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Virginia. The second cohort, launched in May 2018, included Alabama, the District of Columbia, Maryland, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Washington. Participating states entered the collaborative with diverse experiences and needs related to IECMH policy and financing. Some had existing IECMH infrastructure and momentum to build on, while others were in early stages of building awareness about the importance of IECMH. The policy stories included in this article illustrate just a few of the extraordinary accomplishments of the Cohort 1 states that participated in the IECMH-FPP. While the Cohort 2 states are not as far along, we also feature some of their unique achievements to date. Their stories are meant to inspire and offer lessons learned for other states interested in advancing IECMH policy.

Stories of IECMH Policy Action

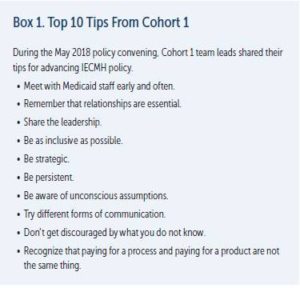

Alaska, Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota1, and Oregon are just a sample of the IECMH-FPP states that have designed and successfully advanced IECMH policy. Their work took on many dimensions. Some states focused on just one aspect of IECMH; others took on multiple projects. While each state effort differs, their stories share common practices related to leadership and collaboration. Each story illustrates key practices and important lessons for states that have an interest in advancing IECMH policy. For more detailed information on the work of the Cohort 1 and Cohort 2 states, please see Box 1 and the Learn More box.

1 While Minnesota was not a member of the IECMH-FPP Cohort 1, they participated in the project as a host state and advisor.

Alaska in Brief

Alaska in Brief

Statewide economic challenges and high adverse childhood experience (ACE) rates opened the door for consideration of IECMH coverage in the state’s Medicaid waiver application.

The Innovation

Leaders in Alaska submitted an 1115 Medicaid waiver2 application in January 2018. One of the primary goals outlined in the application is to increase services for at-risk families and intervene as early as possible to support young children’s healthy development. For the first time, the waiver would allow social determinants of health to qualify individuals for services. Although many states have used the 1115 comprehensive waivers to test and learn about new approaches to Medicaid program design and administration, very few have included a specific focus on IECMH.

2 Section 1115 of the Social Security Act gives the Secretary of Health and Human Services authority to approve experimental, pilot, or demonstration projects that are found by the Secretary to be likely to assist in promoting the objectives of the Medicaid program. The purpose of these demonstrations, which give states additional flexibility to design and improve their programs, is to demonstrate and evaluate state-specific policy approaches to better serving Medicaid populations.

The Process

During the summer of 2016, faced by a growing fiscal crisis, the state Senate passed a comprehensive Medicaid reform initiative. This reform effort called on the Department of Health and Social Services to improve health care and reduce costs by focusing on improvements to Medicaid and behavioral health care. In short, the legislature mandated a redesign of behavioral health services and required the Division of Behavioral Health to apply for an 1115 Medicaid waiver.

Medicaid Reform and Redesign teams (with representation from both inside and outside government, including health, mental health, and the business community) convened beginning in September 2016 to map a reform strategy. At that time there was not a designated representative for early childhood on the teams. In October 2016, the state participated in the IECMH-FPP kick-off cross-state meeting and, as required, the Medicaid director attended. It was a transformational experience, and mindsets shifted with new understanding that there could be a high return on investment when focusing on the critical early years. From that point forward, early childhood representation—primarily though Gennifer Moreau, the Early Child Comprehensive Systems project manager at the time—has been included in the Medicaid Reform and Redesign teams.

With a seat at the table, Moreau was able to increase understanding of IECMH and specifically the cost savings that can be realized if ACEs are reduced. She was also able to help teams understand that the state was missing out on the opportunity to benefit from a higher federal match for services for pregnant women and babies. Even with Moreau’s involvement, there were times when the IECMH focus fell to the sideline, but the Alaska director of Medicaid at the time became an informed advocate and sent a clear message that families with young children should be included in the proposed waiver.

The Behavioral Health Demonstration 1115 waiver application was submitted to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in January 2018. As of July 2019, the state was in negotiations with the federal staff and confident that the waiver was nearing approval. Moreau, now the director of the Division of Behavioral Health Services, will lead implementation of the wavier. Stakeholders across the state are excited about the opportunities it will offer them to better serve young children and families.

Important Lessons

Alaska shared key lessons learned:

- Ensure the Medicaid director has opportunities to learn about the critical development that occurs in the infant and toddler years and how early intervention can be successful in changing life trajectories for young children.

- Educate decision makers about the importance of prevention and the return on investment that IECMH can provide.

- Be thoughtful about the definition of the 0–3 population (e.g., what is zero?) so that it translates across regulatory and funding authority language.

Colorado in Brief

Capitated financing allowed for more flexibility to focus on mental health prevention.

The Innovation

The Colorado Medicaid program contracts with Regional Accountable Entities, which are responsible for coordinating and administering physical and behavioral health services for a designated population with both a per-member per-month payment, as well as incentives, for physical health care and a fixed per-capita payment for behavioral health services. This capitated system allows community behavioral health providers to deliver a host of preventive services to pregnant and parenting women and very young children, including IECMH services.

The Process

The Department of Health Care Policy and Financing supports capitated payments for core behavioral health services. The goals are to reduce barriers to care, focus on value-based purchasing incentives, and provide flexibility to pay for integrated behavioral health services within primary care settings.

Colorado received funding from the federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation in 2014 to support a State Innovation Model (SIM) to integrate primary and behavioral health care and to reform the state’s reimbursement structure. The overall goal of SIM is to increase access to integrated and comprehensive behavioral and primary care services to 80% of Coloradans by 2019. In addition to focusing on integration, SIM applies a value-based payment structure, expands information technology including telehealth, and finalizes a statewide plan to improve population health. The SIM opportunity received significant attention early on from early childhood advocacy, provider, philanthropic, and stakeholder groups. They emphasized the need for high-quality integrated behavioral health services for young children and families, screening for young children, and screening pregnant women and new mothers for depression. These concerns helped shape SIM implementation. The SIM project provides technical assistance to primary and pediatric care practices and community mental health centers.

Contemporaneous to SIM, the Colorado Early Childhood Leadership Commission endorsed an early childhood mental health strategic plan in 2015. One of three priorities of the plan is development of a long-term sustainable financing approach for Colorado’s early childhood mental health system. A workgroup has been tasked with exploring this issue and focuses on:

- using data to inform policy and funding investment opportunities for IECMH;

- advancing recommendations on state policies regarding payer reform, parity, and reimbursement for services that address IECMH needs across the continuum; and

- identifying and disseminating tools that allow providers and families to understand and respond to the mental health needs of young children in their caregiving contexts in ways that can be reimbursable.

As part of this effort, the state commissioned an IECMH Risk, Reach and Resources fiscal analysis. With funding from The Piton Foundation at Gary Community Investments, the Colorado Health Institute analyzed key indicators identified by a stakeholder group to determine IECMH risk, studying the reach of programs that are proven to have a positive effect on the identified risk factors, and compiling data on public and private funds that are invested in these programs. The state hopes to have a clear picture of IECMH. The intention is that the report and accompanying interactive maps will be used by a variety of stakeholders including the governor, legislators, policymakers, funders, and other program directors. These resources will help to illuminate gaps and directions for future IECMH policy and financing.

At the local level, providers are seeing the benefits of the capitated system because it allows them to invest in mental health prevention and early intervention. For example, Lauren Jassil, clinical director of Integrated Outpatient Services at the Community Reach Center in Adams County, Colorado, takes advantage of this opportunity to work with young children and their parents to wrap them in the supports they need. The capitated system provides flexibility to manage funds and direct them toward prevention and other effective and less costly interventions. The Center’s leadership team engages in an intensive strategic planning process to plan the clinical direction of the agency’s services and allocation of funds. For example, when working with very young children who are not presenting with a diagnosable mental health condition, the Center is able to use prevention level codes for billing.

The work is episodic and tailored to what the child most needs. When kiddos come in to us through the prevention lens, we try to assess right away whether the mental health center is the best place or not. We may refer to home visiting from the start to create more of a wraparound plan, or we may refer out to home visiting after the family has gotten their needs met from the mental health center

said Jassil. For pregnant and new mothers, the Center can work with the mother as the client through the postpartum period, which is through 1 year old. Though this flexibility allows the community mental health center to bill for many services that focus on promotion and prevention, leaders of mental health centers still need to seek out additional grants for other aspects of their work (e.g., care coordination, mental health consultation).

Assessing developmental milestones for physical growth was a given for pediatric providers and policymakers alike.

Important Lessons

Colorado shared key lessons learned:

- Make sure there is an individual in state government who understands IECMH, has appropriate levels of authority to advance policy and practice, and can provide leadership on IECMH as part of broader reform efforts to Medicaid.

- Reach out to philanthropy to support services that state and federal funding will not cover, but understand that philanthropic dollars will not provide long-term, sustainable support and instead offer short-term innovation and thought-partnership.

- Partner with Medicaid and request data that can be shared to inform questions and help uncover solutions for expanding utilization, quality, and innovation.

Massachusetts in Brief

Leaders in Massachusetts used an inside-outside government strategy to define and advance an IECMH agenda.

The Innovation

Strong trusting relationships driven by a common interest support active engagement that includes families, mental health providers, early educators, advocates, and state administrators from the Departments of Mental Health (DMH), Public Health, and Early Education and Care.

The Process

Early childhood leaders in the state participated in the IECMH-FPP that began in 2016. Representatives from MassHealth (Medicaid), the Department of Public Health, DMH, the Children’s Mental Health Campaign, and a child psychiatrist formed the state team. They wanted to use the technical assistance offering as an opportunity to work across public and private sectors to coordinate and align efforts. More stakeholders were brought on board following the October 2016 kick-off cross-state meeting, and together they decided that as a next step they should convene an IECMH Summit. Team members believed that the summit could build a “coalition of coalitions” and reach consensus on actionable steps to move the IECMH field ahead in the coming year.

With coordination provided by the Children’s Mental Health Campaign (the principal “outside” partner), Massachusetts held the IECMH Summit in June 2017, and nearly 100 people attended. An inequities panel set the tone. Participants developed a shared framework acknowledging disparities and inequities, particularly for immigrants and people of color. With this framework as a foundation, participants then divided into four groups to explore each area identified as a priority and recommend action steps. The four groups were:

- DC:0-53,

- workforce development and Massachusetts Association for Infant Mental Health (MassAIMH) competencies,

- mental health consultation/expulsion, and

- integration.

The hope was that these conversations would translate into actions that will improve IECMH capacity across all child-serving systems in the state.

Reflecting on the process used to advance an IECMH agenda over the past decade, Christina Fluet, director of planning and policy development, Division of Child, Youth, and Family Services of the Massachusetts DMH commented, “We came to realize it was important to have collaboration at multiple levels—an interagency steering committee that could set the agenda, an interagency workgroup that could implement the agenda, and external partners that could extend the work.”

This inside-outside strategy helps to leverage and maximize resources to put IECMH first.

3 DC:0–5TM: Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood (ZERO TO THREE, 2016) is a tool used by clinicians to accurately diagnose and classify infant and early childhood mental health disorders. The original manual, DC:0–3, was published in 1994 and was followed by the revision version, DC:0-3R, published in 2005.

Important Lessons

Massachusetts shared key lessons learned:

- Practice patience as you continuously bring people together to get to know one another, share information, strategize, and work toward consensus. The process is important.

- Be clear about roles. State agency staff are not allowed to advocate but can educate and inform.

- Build partnerships with entities that can engage in advocacy work

Minnesota in Brief

A commitment to both strategic and serendipitous opportunities built an IECMH system of care.

The Innovation

Leaders in Minnesota pursued an agenda of strategic and serendipitous opportunities to build an IECMH system of care. This effort was guided by a strong commitment to and recognition of the interplay between research, policy, and practice, and of the importance of interagency collaboration.

The Process

In the early 2000s, the Commonwealth Fund launched the Assuring Better Child Health Development Program with an intentional focus on the importance of developmental screenings for young children. From the beginning of this program, the state and key stakeholders took advantage of every opportunity to maximize impact and grow a system that would support the behavioral health needs of young children. As a result, there has been a focus on four activities.

Building state agency collaboration. Unlike all other program grantees that had the state Medicaid office as the recipient of the award, the Minnesota Mental Health Authority applied for the grant, with the support of the Medicaid office. The effort was a collaboration between the two agencies from the start, and over time this collaboration extended to Part C, social services, and other state agencies.

A serendipitous opportunity presented with respect to Part C. The program was under review by the federal government for low enrollment. Glenace Edwall, then the state’s child mental health program manager, was able to help the agency staff understand that if they expanded their net beyond a narrow focus on physical and cognitive disability to identify children on the basis of mental health needs, their Part C numbers would increase. Even more important, they would be able to help children early and then may avoid the need for Part B services, which would be more costly for the state. As a result of this change, they were able to add 11 DC:0–3 (now DC:0–5) diagnosis definitions to Part C eligibility.

Shifting mindsets. Assessing developmental milestones for physical growth was a given for pediatric providers and policymakers alike. It took some time, though, for them to recognize the importance of screening for behavioral health as well. Part of the problem was that there was little confidence that a child who performs poorly on the screen would have access to the requisite behavioral health services in the community. Also, there was concern about labeling young children. Edwall and others insisted that a possible lack of services did not justify a decision to not screen. Providers and policymakers recognized that screening may, in fact, become a driver for expanding access to evidence-based behavioral health services for children who might avoid more intensive and costly services later. “The director of Medicaid at the time understood and ultimately said, ‘Of course we should do this, and what do you need to get it done,’ ” remembered Edwall.

Opportunities to advance IECMH policy span a continuum from promotion to prevention, to developmentally appropriate assessment and diagnosis, to treatment.

Briefing policymakers. The provider community, the state chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, and Jane Kretzmann at the University of Minnesota worked to unite research with policy to create a broad appeal for IECMH. Kretzmann played a key role in raising awareness among policymakers about brain research and ACEs. With strong connections to members of the state legislature, the National Alliance on Mental Illness chapter was able to offer suggestions for legislation. Further, health plan administrators, mental health professionals, and state agency leaders came together as part of the public–private Minnesota Mental Health Action Group to identify policy needs (e.g., resources for training and other infrastructure enhancements, a model benefit set) and advance recommendations to policymakers. More than 3,000 people across the state weighed in on the Action Group’s recommendations, demonstrating to the governor and state policymakers the broad appeal for improvements in the mental health system, including IECMH.

Building capacity of providers. Efforts have focused on training community providers (e.g., community mental health, early intervention, child welfare, Head Start) on topics including DC:0–3R/DC:0–5; evidence-based practices; developmental trajectories; and neurodevelopment and the efforts of toxic stress, trauma, and resilience. Minnesota’s other activities include offering an Infant Mental Health certificate; developing regional centers of best practice; pursuing multigenerational interventions, including development of partial hospitalization programs for mothers and infants and more integrated care models; and providing consultation to child care and supporting routine screening and referral in home-visiting programs. The following are other key achievements in Minnesota:

- Since 2004, approximately 3,000 clinicians across the state have been trained in DC:0–3R/DC:0–5.

- The state offers a free consultation meeting once a month on the use of the DC:0–3R/DC:0–5.

- Since 2008, the state has trained early childhood mental health professionals in the following evidence-based interventions: Attachment Bio-behavioral Catch Up, Child–Parent Psychotherapy, and Parent–Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT). The state is working with the developers of those interventions to also train certified clinicians as supervisors and trainers in their clinics.

Important Lessons

Minnesota shared key lessons learned:

- Stay focused and take advantage of every opportunity that may present to bring you closer to an integrated statewide system of care for IECMH.

- Make friends broadly. Learn their systems. Look for ways to infuse IECMH into their work.

- Create an agenda where research, policy, and practice are in continuous cycles of communication and mutual improvement.

Oregon in Brief

IECMH is recognized as a reimbursable treatment.

The Innovation

Oregon prioritizes evidence-based treatments including IECMH as part of the state’s Medicaid program. The focus on prioritizing health issues dates back to a 1994 Medicaid waiver and undergoes regular refinement, revision, and expansion.

The Process

With a focus on promoting evidence-based treatments, the state has taken steps over the years to increase support for IECMH services.

Annual review of prioritized list. The Health Evidence Review Commission completes a regular review cycle of each cluster of conditions and related treatments. On the basis of the information available, treatments may move up or down on the list to reflect the latest research and understanding of effectiveness. The 2016 revision added behavioral health procedure codes to the line for abuse and neglect as a primary diagnosis, added a code for conduct disorder (specified or unspecified) for children 5 years and younger who cannot be diagnosed with a more specific mental health diagnosis, and added a new diagnostic code for other specified problems related to the primary support group (e.g., family discord, family estrangement, high expressed emotional level within family, inadequate family supports and/or resources, inadequate or distorted communication within family), among other changes.

Diagnostic crosswalk aligns Medicaid reimbursement policies. When Laurie Theodorou, early childhood mental health policy specialist, Oregon Health Authority, began working for the Authority in 2014, she was surprised to discover that early childhood behavioral health providers were not fully aware of the reimbursement codes for the services they provided. Since then, she has worked with a core stakeholder group to create the Oregon Early Childhood Diagnostic Crosswalk which bridges the DC:0–5, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (World Health Organization, 1992), and the related line on the prioritized list. The crosswalk helps behavioral health providers better understand what services are reimbursable. The state took several steps to disseminate the crosswalk, including posting it on the Oregon Health Authority website and providing presentations across the state to train providers, mid-level managers, billing staff, directors, chief executive officers, and coordinated care organizations on its use.

Expansion of evidence-based treatment. In 2013, the legislature invested $2.4 million each biennium to grow PCIT. The effort expanded from one site offering PCIT in 2004 to 16 counties with nearly 40 locations in 2014. Every year, the state reports on pre–post outcomes of children who receive PCIT treatment. The data is shared with the Children’s System of Care Advisory Council and the state legislature.

Additional supports. The early childhood investment funds support workforce development via scholarships to the Infant Toddler Mental Health Graduate Certificate Program at Portland State University. The Integrated Health Services, Public Health, and Maternal Infant Early Childhood Home Visiting Divisions of the Oregon Health Authority coordinate with the Early Learning Division and community stakeholders to develop a system of care for all young children. The vision includes an array of providers skilled in core competencies such as the Oregon Infant Mental Health Endorsement, certification in high-fidelity early childhood mental health therapies, and registration on Spark, Oregon’s child care Quality Rating and Improvement System.

Important Lessons

Oregon shared key lessons learned:

- Be clear about the difference between social–emotional wellness and mental health treatment. It is important to know what point on the continuum of care is being addressed and match the providers with appropriate training.

- Train providers, supervisors, and leadership in mental health organizations to understand what is reimbursable by Medicaid.

- Hire an advocate at the state level who understands IECMH research and effective models and who “doesn’t give up, ever.”

A Snapshot of Cohort 2 Achievements

Although the Cohort 2 states have just come to the end of their technical assistance period, they have already made remarkable progress. A summary of key themes and a few examples of each are listed here.

All states built cross-sector awareness and support for IECMH by engaging additional stakeholders in their work, mapping their systems’ assets and gaps, and/or launching strategic planning.

- Alabama, Maryland, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Washington held IECMH summits or policy meetings to educate stakeholders and identify IECMH priorities.

- The District of Columbia created a map of IECMH services and supports across the continuum to ensure the cross-sector provider community understood the current landscape. They also developed a Medicaid funding gap analysis to inform policy action. Both were further disseminated at the Mayor’s 2nd Annual Maternal and Infant Summit and a cross-sector Early Childhood Summit in September 2019.

- New Mexico created a collaborative with representatives from state agencies and private organizations to develop shared IECMH priorities and inform existing planning efforts at the Department of Children, Youth and Families. The department named infant mental health as a strategic priority and successfully achieved a $1 million increase in funding for IECMH in the FY2020 state budget.

- Maryland partnered with ZERO TO THREE’s HealthySteps leadership to explore financing strategies for primary prevention and integrated care in a cross-sector summit.

Several states improved IECMH assessment and diagnosis by taking steps to implement DC:0–5.

- Tennessee developed a DC:0–5 crosswalk to support clinicians in billing Medicaid and created a new bundled Medicaid billing code for IECMH-related assessment.

- As a result of peer-to-peer conversations across teams, Alabama, North Carolina, and Tennessee pooled resources to host a regional train-the-trainer DC:0–5 session.

- New York expanded DC:0–5 training statewide with Preschool Development grant funding. Maryland and New Hampshire are also working with partners to offer DC:0–5 training.

All states had a high-level representative from Medicaid participate in their teams as required by the technical assistance agreement, which facilitated relationship-building and collaboration with state Medicaid offices.

- New Hampshire convened a sub-workgroup with Medicaid to identify and address needed Medicaid changes to allow Community Mental Health Centers to bill for DC:0–5 assessment and diagnosis, expand allowable sessions for assessment, and develop preventative DC:0–5 criteria for Children’s Behavioral Health.

- New York leveraged timing of implementation of the First 1,000 days on Medicaid Initiative to advance their priorities related to dyadic therapy, braided/blended funding, and mental health consultation.

- Washington worked with Medicaid staff to field an IECMH survey and conduct interviews with clinicians serving young children about barriers to Medicaid billing.

Many states concentrated some of their efforts on increasing the capacity of the workforce to support IECMH.

- New Hampshire and Tennessee engaged community partners and funders in conducting workforce development needs assessments.

- Leaders in South Carolina’s Department of Mental Health and Department of Social Services identified IECMH work-force goals, such as: ensuring at least one person at each Community Mental Health Center will have specialized training in serving children under 5 years old, and building IECMH expertise among child welfare staff. The Infant Mental Health Association is working with both departments to advance these goals.

Some state teams leveraged existing federal grants to pursue IECMH priorities or included IECMH activities in new grant applications.

- Nevada included a focus on IECMH in a new Health Resources & Services Administration Pediatric Mental Health Care Access Program that is supporting DC:0–5 training.

- South Carolina and the District of Columbia have integrated some IECMH priorities into their Preschool Development Grant Birth to Five needs assessment and strategic planning efforts. The District of Columbia also incorporated them into its Pritzker Children’s Initiative Prenatal-to-Age Three State Planning Grant.

- Alabama built on the momentum of their Project LAUNCH work to strengthen a partnership between the Department of Education, the Department of Mental Health, and Medicaid. Working together, they changed a Medicaid rule to allow independent mental health providers to bill Medicaid under their own licenses (increasing capacity for providers serving very young children to bill), requested additional state funding to sustain IECMH services offered through Project LAUNCH (which ends soon), and are exploring potential to collaborate on perinatal mental health services through Medicaid’s new regional networks, set to start in October 2019.

- The Maryland Behavioral Health Administration built on the momentum of Maryland LAUNCH and ZERO TO THREE policy work under the Center for Excellence for IECMH to create a new position within the Child and Adolescent Unit titled, “Chief, Early Childhood Mental Health Services.”

Overall, the states appreciated the opportunity to be part of the IECMH-FPP learning community. Comments included the following:

- “Being able to hear what other states have done and how they accomplished their work was invaluable to us. This is new territory for us, and it was great to have the team hear counterparts from other states talk about strategies and benefits. Follow-up from our assigned [technical assistance] person helped to keep us moving forward, however slightly, with multiple demands on our time.” New Hampshire

- “This collaborative was invaluable in bringing together key staff across agencies and organizations who share the vision and dedication to this important work with infants, toddlers, and young children.” New York

- “Having the requirement that a high-level person within our Medicaid agency be on the team and attend the face-to-face convening was very beneficial. This helped her understand IECMH financial policy, Medicaid’s important role in being a change maker, and gave her an opportunity to meet and talk with Medicaid reps from other states.” Alabama

- “I cannot express enough appreciation for being part of this project. I am confident that the work we did over the past year will continue to advance in the upcoming years.” Nevada

Conclusion

Opportunities to advance IECMH policy span a continuum from promotion to prevention, to developmentally appropriate assessment and diagnosis, to treatment. The policy stories included in this article illustrate just a few of the remarkable accomplishments of the states that have participated in the IECMH-FPP. They are meant to inspire and offer lessons learned for other states interested in advancing IECMH policy. Their stories demonstrate that, despite funding constraints and the challenging political landscape, there are always opportunities to take action to increase access to high-quality mental health services for pregnant women, young children, and families.

Authors

Julie Cohen, MSW, is associate director of the ZERO TO THREE Policy Center. During her 20-year career at ZERO TO THREE, Ms. Cohen has worked on a wide range of policy issues impacting infants and toddlers including infant and early childhood mental health.

Deborah Roderick Stark, MSW, is a nationally recognized consultant focusing on child and family programs, research, and policy. She has more than 25 years of experience working with foundations, public agencies, the nonprofit community, and federal legislators.

Jamie Colvard, MPP, is director of state policy with the ZERO TO THREE Policy Center. She supports states to identify and move infant–toddler priorities related to early childhood mental health, early care and education.

Suggested Citation

Cohen, J., Stark, D. R., & Colvard, J. (2019). Advancing infant and early childhood mental health policy in states: Stores from the field. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 40(2), 37–44.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

World Health Organization. (1992). International classification of diseases (10th ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

ZERO TO THREE. (1994). Diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood (DC:0–3). Washington, DC: Author.

ZERO TO THREE. (2005). Diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood, revised edition (DC:0–3R). Washington, DC: Author.

ZERO TO THREE. (2016). DC:0–5TM: Diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood. Washington, DC: Author.