Marsha Gerdes, Crystal Anokam, Emma Blackson, and Ellie Segan Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; MaryKay Mahar, Beth Huertas, Bernadette Lewis, and Cynthia Richards, Public Health Management Corporation Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Abstract

This story from the field describes the experiences of 11 early childhood education centers in Philadelphia that were part of a project to implement Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS). It tells of the many challenges they faced during the COVID-19 pandemic and calls for racial equity and social justice and how these events impacted early childhood education providers. The authors highlight the resilience and adaptability of these centers and of the PBIS external facilitator team in adapting to the new normal.

In 2019, a team of early childhood education directors and staff, psychologists, research staff, and early childhood education coaches began working together on implementing Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS) in 11 early childhood education centers. PBIS is a systematic framework based on the Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning pyramid model to support social and emotional development in schools (Fox & Hemmeter, 2008; Muscott et al., 2009; National Center for Pyramid Model Innovations, 2021; Pennsylvania Positive Behavior Support, 2021). PBIS practices building relationships among staff, students, and families; creating positive classroom atmosphere; sharing center-wide and developmentally appropriate classroom expectations; and creating structured classroom environments as core elements of implementation (Pennsylvania Positive Behavior Support, 2021).

PBIS implementation was paired with equity trainings and family engagement strategies in some of the centers. The centers that are a part of this Philadelphia project joined with the goal of quality improvement and with the goal of reducing expulsion and suspension. The centers, which range in size from three to eight classrooms, all provide services for children infancy or toddler age through preschool, with some also providing afterschool care. Centers included families who received early childhood education support through early childhood education subsidy, Head Start, PreK Counts, and PHLpreK, as well as self-pay. Each center enrolled children reflecting the diversity of Philadelphia neighborhoods including Black, White, Arabic, Latino, Asian, and many other races and ethnicities.

The Impact of COVID-19

Implementation of PBIS is difficult no matter the circumstances; it requires early childhood education centers to undergo major cultural shifts, make substantial changes in the structure of leadership, and adopt new frameworks (Benedict et al., 2007). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and calls for racial equity and social justice have significantly shifted the pathway to implementation in our project. PBIS was not entirely derailed, but the pandemic pivoted the capacity of early childhood education centers to pursue quality in the same way. Financial challenges and sustaining new health and safety practices took money, time, and emotional stamina, which left centers with less capacity for quality improvement efforts. We want to tell you our story of the challenges and the positive aspects from the Early Childhood PBIS project in Philadelphia.

Challenges

Early childhood education directors have always been recognized and honored for their strength, dedication to the children, willingness to run a business under an almost constant threat of demise, and their adaptability to change. Even from this position of strength, the pandemic has hit hard.

Financial Effects: Closures

In Pennsylvania, the closure of early childhood education centers was mandated on March 13, 2020. In Philadelphia, out of more than 1,600 providers, only 19 centers originally applied for waivers in early April 2020. None of the 11 centers working to implement PBIS chose to apply. Staff members from each center were at home. Families were caring for their children at home or seeking help from others. More than half of our centers continued to pay their staff or worked hard to ensure that their staff members were successful in obtaining unemployment benefits. Staff members often used this period to complete free virtual professional trainings that were offered locally. During this time, some of the center directors became leading voices in advocating for state policies that would ensure the survival of their centers and for city policies to bring COVID vaccines to early childhood education staff. These requested changes included policies that would change child care subsidy payment to be based on enrollment instead of attendance, increase in base rates, and provide personal protective equipment (PPE). Almost all our centers turned their attention to their families with phone calls, virtual experiences, meeting needs of families through the provision of food, and other supports. Center directors were depleting their business savings and sometimes even their personal savings to do these things.

Financial Effects: Reopening

When Pennsylvania allowed centers to reopen, multiple sources of COVID-related information caused confusion, competition for PPE, and potential unnecessary extra costs. Programs were not clear on the hierarchy of guidance provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Pennsylvania’s Office of Child Development and Early Learning (OCDEL), and Philadelphia’s Department of Public Health (CDC, 2020; Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, 2020; Philadelphia Department of Public Health, 2020). In addition, it was not clear how compliance with recommendations versus regulations would be monitored, which impaired centers’ timely business decisions. During this period, the support from the local early childhood health consultants and the health department were very helpful.

It took even longer for centers to source the needed materials that they were mandated to have. They found themselves in competition with health care providers and public schools that remained open for the same masks, gloves, and thermometers. These issues were resolved, but the amount of attention and commitment it took each director to solve this cannot be overstated. The lack of clarity and their worry about safety led some of the centers to adopt safety measures that were not connected to greater mitigation of risk and were often costly, such as taking temperatures 3 times a day or outside/inside shoe policies. The development of COVID-related policies, the needed training of staff, and the communication with families also took time. The transparency and clarity of the communication with families encouraged them to come back and be part of that community again.

The most significant long-term financial effect of reopening turned out to be decreased enrollment combined with increased costs due to COVID demands including lower ratios, cohort group planning, and additional administrative and custodial support. The decision of parents to return to early childhood education programs was a strong statement in Philadelphia that early childhood education is essential for families. Those who returned demonstrated a trust in the care and carefulness of early childhood education staff. The lower rate of return reflected for many a slow growth of employment in Philadelphia, as many businesses have remained closed and some centers decreased enrollment in order to comply with cohorting and social distancing guidelines. One center needed to rent and license more space in order to serve school age children. The centers experienced a loss of enrollment ranging from 27% to 73% of children returning. Of the 11 centers, 9 opened with at least one fewer open classrooms. One center had to reduce its number of employees almost by half to stay in alignment with CDC guidelines around physical spacing during nap and mealtimes.

Stress

Stress during the COVID-19 pandemic is something we all shared. For the early childhood education directors, their worry was intense due to concerns for the health and safety of their immediate family, their staff, the children and families, and their neighborhood. Stress was also related to workforce challenges. For example, many staff members would not return following closures due to health concerns, fear of being infected with COVID-19, parenting and schooling responsibilities, and the inability to get to work due to reductions in public transit schedules and routes. The fear of liability was high and complex. Early childhood education directors engaged in long conversations with their insurance carriers and advocated with the state for a waiver from liability since they were an industry working in time of crisis.

Staff Challenges

Maintaining a consistent high-quality staff has always been a challenge in the early childhood education industry. The challenge is rooted in low salaries, limited benefits, lack of professional requirements for the job, and the high level of difficulty of the position (Whitebook, 1999). The pandemic exacerbated the rate of turnover, retirement, and mandated exclusion for symptoms. The high base rate of turnover increased as staff needed to stay home to care for their children, needed to stay on unemployment, or did not choose to work in a stressful environment. In addition, three centers experienced a change in director. There was a mean loss of 60% of staff (ranging from 10% to 75% loss). In early childhood education communities, the loss of staff was like losing part of their family. One of the centers dropped out of the project during this period. We know that they were struggling to retain staff members and stay open and likely did not have the capacity to take on PBIS at this time.

COVID-19 Health and Safety Measures

While early childhood education centers have been guided for many years to conduct what the industry terms “effective personal care routines”—including good hand hygiene, clean toys, and protocols for children who were ill—the breadth, scope, and depth of the CDC guidelines were a major challenge. From the perspective of the early childhood education provider, the stakes of maintaining these guidelines were much higher. Each new health or safety step seemed to come with an additional cost, the need for an additional staff, and changes to the daily schedule. For example, instituting drop off and pick up outdoors brought the cost of a staff member to greet and take each child to their room. The temperature and symptom screening brought the cost of thermometers, smartphone apps, paper, pens, and staff. Additional sanitization measures brought the cost of cleaners, new washing machines, and new sinks. Using cohorts created a sense of isolation and loneliness for many teachers who were restricted to their room.

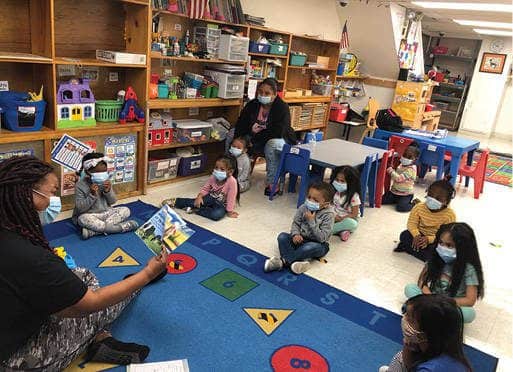

Early childhood education directors have always been recognized and honored for their strength, dedication to the children, willingness to run a business under an almost constant threat of demise, and their adaptability to change. Photo: Provided by Care-A-Lot Learning Center

Closures

Of the 11 centers, 8 had to close down classrooms or the entire center because of COVID exposure. In the beginning of reopening, COVID scares were time consuming. An example of a typical confusing COVID scare was when a teacher’s brother-in-law, who she saw for dinner, learned that his girlfriend’s mother was diagnosed with COVID. It was not until there was more clarity about indirect exposures that the stress was reduced. Clarity was a challenge due to the limited access to health department professionals in a position to guide policies and procedures.

Social Distancing

The CDC recommended restricting nonessential visitors to centers, which restricted help from outsiders who were typically there to support the centers. Much of that work shifted to virtual delivery, and some work simply stopped. These support staff include early intervention (EI) providers, behavioral health supports, personal care assistants, food providers, bus drivers, and early childhood technical assistant staff. This restriction also included our team of PBIS external facilitators. As EI service providers shifted to tele-intervention, the need for early childhood teachers to support participation in EI services within typical classrooms grew. These teachers often needed to devote individual attention to each child attending an EI tele-intervention session in order to set up the videochat meeting and ensure engagement with the screen during service. Additional staff members, however, were not often available to reduce overall classroom ratios while this was occurring.

Centers found themselves in competition with health care providers and public schools that remained open for the same masks, gloves, and thermometers. Photo: Kevin Chen Images/shutterstock

Social distancing guidelines defined parents as “nonessential” visitors, which moved drop off and pick up outside the front door, taking away a natural opportunity to build supportive relationships and good communication between parents and teachers. Traditionally, early childhood education centers become a community for families based on friendships, birthday parties, and shared care. Social distancing diminishes these opportunities for connections. For our PBIS coaches, it meant that the weekly visits—to build relationships, to observe in the classroom, and to offer recognition for jobs well done—halted and were replaced with calls, videochat meetings, and resource sharing.

Calls for Racial Equity and Social Justice

Waves of protests with calls for social and racial justice occurred during the summer and the fall in Philadelphia. In October 2020 in West Philadelphia, the city witnessed the police shooting of Walter Wallace, Jr., a young Black man in the midst of a mental health crisis. The tension, the sounds of sirens and helicopters, the blocked streets, and the distress were palpable throughout the city. These events occurred mere blocks away from early childhood education centers. The staff came to work not having had the time to process what they saw. Many centers engaged in discussions on their personal roles in advocating for racial justice and sought out resources on dismantling bias and discrimination, while promoting equity. Two centers reached out to us to facilitate equity training sessions, knowing that we had provided these at three of our centers. As a part of the early childhood PBIS project, we were implementing equity-training sessions for early childhood education teachers. These included three different sessions that focused on personally mediated racism and bias, systemic and institutional racism and bias, and internalized racism and bias. Each session also included strategies to mitigate discrimination and bias in the early childhood education setting, such as mindfulness, building empathy, and talking about and celebrating diversity in the classroom. These sessions provided staff with a much-needed space to hold conversations on what was happening in the city and across society, and how to engage with children and families they serve in an equitable way. One center chose to take a formal pause in the project to allow their staff and center more time to heal and come together. One group of centers added a new image to their logo to represent the diverse community they serve and represent “kindness” and to provide a platform to open discussions. During this period, PBIS staff offered statements of support, training opportunities, and resources placed into an easily accessible padlet, which is a web app that supports an online bulletin board (see an example in the Learn More box). On monthly calls among the early childhood education center directors, opportunities to share feelings were offered but, in fact, not many used this platform to share their feelings. It may have been that they preferred sharing within their center.

New Approaches in PBIS During the Pandemic

As we designed the early childhood PBIS project, we hoped that the centers would create a support network. Community building occurred through shared training or conference calls.

Community of Learnings Became Communities of Support

An early childhood PBIS newsletter had been started that highlighted the newly evolving PBIS structures and successes at each center. During the pandemic, the community of learning was also a community of support. Support was greatly needed, as many directors and staff members were missing lunch and conversations with peers. We established monthly calls in May 2020 to allow the centers to share their experiences. Seven of our centers were consistent participants in those calls. The focus was often on the mutual struggles with reopening, adhering to CDC guidelines, and how to provide better early childhood education in the midst of a pandemic. The PBIS coaches also shared resources regarding PPE, family engagement, and setting up virtual classrooms. More resources were placed into an online padlet system.

Alternative to In-Person Classes

Centers found ways to reach out to their families and the children, including connecting families with food resources, solving housing crises, and helping families find alternative programs. Initial efforts to provide early childhood education virtually started with emailing activities and play ideas or a phone call to check in and changed over time to well-organized virtual classrooms. Our centers explored a number of different software platforms such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Brightwheel, and YouTube, and followed an iterative pattern of fine-tuning the “class” until they found a successful pace. Teaching and hosting on a virtual platform was a huge undertaking for sites. Teachers had to adjust the daily flow, create new content, and learn new ways to keep preschoolers engaged all while managing the platform. The limitations of children’s ability to pay attention to a screen were also apparent. Like during in-person, activities are best kept short, transitions need to be planned, and even a visual schedule continues to be helpful. Some centers used these platforms to open opportunities to safely discuss unmet needs of the family and any concerns the family might be facing. Centers also adapted how they were reaching out to families with the creation of virtual tours, padlets for families, and virtual back-to-school nights.

Virtual Classroom Observations

A core element of PBIS implementation is classroom observations. We used the Teaching Pyramid Observation Tool and Teaching Pyramid Infant Toddler Observation Scale (Hemmeter et al., 2014). Without access to the classrooms, these observations became a challenge.

Observations form a basis for coaching and identification of strengths and areas to focus on in coaching. We adapted our methods to include the use of tablet computers, video live feeds from classrooms, and supplemental phone connection. The observations were broken up into two parts: a classroom tour and observations of a variety of classroom activities. We were impressed with how flexible the centers were in accommodating these changes. It was remarkable to see how a masked teacher can use voice, laughter, and movement to guide a class, encourage peers, and ease transitions. There were technical challenges of poor WiFi, muffled sounds, and blocked views. We might have missed a few words during each observation and missed seeing a corner of a room (behind where the camera was located), but we were able to capture tone and intent and could see teaching and redirection when it happened. An opportunity that we missed was to record these observations and offer these recordings to the teachers for self-examination and self-identified priorities and goals.

Support From Government and From Philanthropy

Financial supports came from a variety of sources. One center director said,

The positive experiences for me was my eligibility for the PEFSEE [Philadelphia Emergency Fund for Stabilization of Early Education], the PPP [Paycheck Protection Program] loan, the CARES funding, and grants that made it possible for me to keep my staff paid full-time wages, provide staff with all [paid time off] earned from March 16th to reopening on June 29th, purchase PPE, make repairs, and pay all the bills for our facility’s operation and maintenance. I was fortunate to retain my staff despite low enrollment and sustain my center financially. If I had not received any funds, I definitely would have had to close our doors.

The most significant long-term financial effect of reopening turned out to be decreased enrollment combined with increased costs due to COVID demands including lower ratios, cohort group planning, and additional administrative and custodial support. Photo: Provided by Care-A-Lot Learning Center

Early childhood development and education has been at the heart of the missions of many philanthropic foundations in Philadelphia. The William Penn Foundation and Vanguard Strong Start for Kids joined together to establish PEFSEE, which aimed to ensure that Philadelphia’s early learning sector could weather the COVID-19 crisis. PEFSEE provided grant funds to minimize the loss of capacity and expertise in the sector so that children and families continue to have access to high-quality early learning opportunities once this crisis has passed. In addition, the William Penn Foundation funded Public Health Management Corporation to supply free PPE to over 900 early childhood education providers in Philadelphia and funded accessible health and safety resources to support providers in using their PPE and meeting OCDEL guidance/CDC guidelines, such as child care health consultation, open office hours, and topical webinars. These webinars were done in partnership with Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. For our PBIS project, Vanguard provided stipends for PBIS participation in the 2020–2021 school year ranging from $333 to $2,333 based on the size of the centers. For this, we are grateful on behalf of the centers, and we are grateful the programs found value in the project and continued participation through a uniquely challenging time.

Impact on PBIS Implementation

The pandemic derailed much of the progress that many centers were making. For example, some centers had started core leadership team (CLT) meetings that stopped, and when the center reopened, little effort was initially directed toward re-engaging the CLT or moving forward with PBIS strategies.The inability to meet in-person, reduction in available time for planning due to decreased enrollment and staffing, and the prioritization on health and safety steps impacted the ability to move forward, and directors took the lead on most decisions. In some cases, significant changes in staff derailed the CLT meeting. If the internal facilitator left, as was the case in four centers, there was no one to start up the process. Only one center held a CLT during the period the centers were closed. Also, the pause in CLT meetings was influenced by the fact the CLTs were so new that they had not yet proved of use or importance to the functioning of the center. Other efforts were also disrupted. Some centers were halfway through the process of establishing positively stated center-wide expectations and chose to restart the process.

The temperature and symptom screening brought the cost of thermometers, smartphone apps, paper, pens, and staff. Photo:maxbelchenko/shutterstock

Because of the increased demands and stress that centers face daily, the buy-in to PBIS and quality efforts wavered in some centers. In addition, the lack of access to individual teachers has had a negative impact on buy-in. Because of CDC guidelines, teacher cohorting, and 100% virtual coaching, PBIS coaches shifted to rely on the directors to act as internal facilitators in the centers. This new dynamic created challenges for some centers; one center expressed that they did not feel they were receiving the classroom coaching they were expecting. Other centers have directors with strong visions of how to employ quality efforts in the midst of the pandemic that were coordinated with PBIS efforts.

PBIS implementation builds on relationships, on shared goals and expectations, and on investing in strategies to reach a goal. We relied on face-to-face experiences to build those relationships during our first year. Although we substituted videochat calls, phone calls, and emails, it was hard to keep those budding relationships strong. We were begging for connection. Often our emails or calls were not returned for weeks. As one center director said, “The stress of multiple pandemics has thrust us all into survival mode. PBIS is still present but the formalities have taken a backseat for now.”

PBIS coaches were an endless source of ideas and innovations of ways to reach out to centers. Individual staff coaching and practice-based coaching from external facilitators became nearly impossible, so coaches had to rely heavily on working with the directors and administrators to become internal facilitators themselves. But because administrators were spending more time in rooms due to staff outages, they had limited time to fulfill that role. In addition, PBIS coaching shifted to include open office hours, mini professional development session on PBIS practices, a focus on training internal coaches on PBIS and place-based coaching strategies, adjusting implementation plans, adjusting schedules to allow for shorter meetings, and discussions via emails.

Progress Toward Quality Using PBIS

Despite the challenges and the stresses, we have seen the centers move forward. Each active center created a new strategic plan. There is a current refocus on establishing a routine CLT. Those centers which lost their internal facilitators have identified new ones. Participation in trainings increased. A network of support among the sites has grown and become a community of practice. New technology is in place for coaching, for classroom observations, and for communication among staff. Six centers received the Pennsylvania PBIS Network Participating Site badge. That badge was awarded to sites to acknowledge their great efforts to pursue fidelity that couldn’t be obtained due to the pandemic. Each site along with their EC PBIS coach submitted an application based on surveyed staff, updated data, classroom observations, and implementation plans.

Business and Financial Support Is a Quality Improvement Initiative

The pandemic revealed in stark tones the vulnerability of the early childhood education business model and the unfunded activities that program leadership regularly take on because of their unwavering commitment to providing high-quality early childhood education. To meet this commitment in these programs, directors often assume the responsibility of being the curriculum coordinator, budget controller, special education coordinator, and principal. In most elementary schools, these roles are spread across several people. The stress and time-consuming toll of financial worry, along with the reality of making hard staffing and programmatic decisions to stay afloat, has been the prominent story of programs since March 2020. When concerns are on finances and regulation, the attention to teacher training and the focus on quality improvement are diverted. Quality improvement efforts, when joined with advocacy for increased reimbursement rates to reflect cost of care, for living wages for early childhood education staff, and with paid sick leave, will make center staff stronger and more effective and move the center to quality improvements. The association between financial stability and early childhood education quality, child well-being, and school readiness needs to be recognized.

Summary

The focus that each early childhood education center needed to have on the health and safety practices and the financial stress of low enrollment took time and emotional stamina. Was there time and stamina left to implement PBIS? We are seeing positive steps forward toward PBIS implementation as CLT are being reestablished, there is increased interest in trauma informed strategies, visual schedules are in action, and new center-wide expectations reflect lessons learned over the year. We are optimistic that our efforts are providing a solid PBIS foundation. No matter how that turns out, all 11 centers have our admiration and respect for trying.

The pandemic revealed in stark tones the vulnerability of the early childhood education business model and the unfunded activities that program leadership regularly take on because of their unwavering commitment to providing high-quality early childhood education. Photo: Stephen Bobb

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of Arch Street Preschool; Care-a-lot Learning Center, LLC; Child Space; Kinder Academy Castor; Kinder Academy Mayfair; Kinder Academy Rhawnhurst; Little Learners Childcare Center. LLC; Little People Village I and II; St. Mary’s Nursery School; and Smart Beginnings Early Learning Center for their contributions to the work described in this article. The authors also thank Vanguard Strong Start for Kids and the William Penn Foundation for the support of this project.

Authors

Marsha Gerdes, PhD, is a senior psychologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Policy Lab. She is a licensed psychologist who specializes in early childhood. Her research over 30 years has focused on developmental outcome of medically at-risk infants, developmental screening and access to early intervention services, quality improvement in early childhood education, and supporting the role of parents as teachers.

Crystal Anokam is a clinical research assistant II at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, PolicyLab. She received her bachelor’s degree in public health from Temple University. Currently, she works on several research studies related to positive behavior supports and equity for children in early childhood education centers across Philadelphia. In her previous research experience, she has worked within adolescent health working to improve communication between parents/caregivers and adolescents about sex and to educate families about teens’ need for reproductive health.

Emma Blackson, MPH, MS, is a clinical research assistant II at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, PolicyLab. She obtained a bachelor’s degree in public health from Temple University, then a master’s in public health and master’s of science degree in social policy, both from the University of Pennsylvania. Her research experiences focus on studies to promote racial equity and positive behavior supports for children in early childhood education centers across Philadelphia. She has spent 5 years working with children from 3 to 17 years old in early childhood education, after-school, and summer programs which have guided her research.

Ellie Segan is a clinical research coordinator I at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), PolicyLab. She received her bachelor’s degree in human development and family studies from Penn State University and holds a Gundersen National Child Protection Training Center certificate in child advocacy studies. Prior to joining CHOP, she was a research assistant for an infant sleep project at Penn State University and for Johnson & Johnson’s Consumer Baby Innovations team. Currently, she is completing her master’s degree in experimental psychology at Saint Joseph’s University.

MaryKay Mahar, MS, is currently the senior director of early learning in the Child Development and Family Services department at Public Health Management Corporation. She holds a master’s degree in educational psychology from Temple University. Her 20-year career in early childhood education includes experience as an infant–toddler teacher, early childhood education center director, and local Quality Rating and Improvement System implementation leader. Her diverse roles offered insight into the challenges teachers and program operators face in providing trauma-informed and nurturing environments for young children. Her professional investment lies in ensuring the early childhood workforce is equipped to provide optimal interactions, particularly for vulnerable children where secure attachment, screening, and developmental supports can mitigate lifelong effects of poverty.

Beth Huertas, MS, is the early childhood Positive Behavior Intervention Support project manager at Public Health Management Corporation. She holds a master’s degree in multicultural education from Eastern University and a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education and elementary education from Elizabethtown College. She is also a certified instructor through the Pennsylvania Quality Assurance System. Her professional background is diverse with both administrative and classroom experiences. She believes that hands-on learning is an essential part of the education process and that professional development and coaching are needed to provide practitioners with opportunities.

Bernadette Lewis, MS, is an early childhood behavior intervention support coach at Public Health Management Corporation. She holds a master’s degree in early childhood education and special education from Temple University and bachelor’s degree in elementary education. She is a certified instructor through the Pennsylvania Quality Assurance System. Her background is primarily in the area of special education and early childhood mental health with more than 40 years of administrative and classroom experience.

Cynthia Richards, MFT, is an early childhood behavior intervention support coach at Public Health Management Corporation. She holds a master’s degree in marriage and family therapy and a bachelor’s degree in family and child development. She has spent 15 years of her professional career supporting and supervising services to children and families, which includes 7 years directing early childhood education programs. In addition, she has provided coaching supports to early learning providers, assisting with program quality improvement, as well as the introduction of the Pyramid Model framework and implementation of program-wide Positive Behavior Intervention Support practices and strategies.

Learn More

For more information about our Early Childhood Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS) COVID supports padlet: link

For more information about PBIS in Pennsylvania:

Pennsylvania Positive Behavior Support: link

National Center for Pyramid Model Innovations: link

To see a sample of our Early Childhood PBIS newsletter: link

Suggested Citation

Gerdes, M., Anokam, C., Blackson, E., Segan, E., Mahar, M., Huertas, B., Lewis, B., & Richards, C. (2021). Adaptability and resilience in early childhood education during a pandemic: Meeting challenges, maintaining quality, and creating networks of support. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 41(4), 17–24.

References

Benedict, E. A., Horner, R. H., & Squires, J. K. (2007). Assessment and implementation of positive behavior support in preschools. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 27(3), 174–192. link

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Guidance for child care programs that remain open. link

Fox, L., & Hemmeter, M. L. (2008). A programwide model for supporting social emotional development and addressing challenging behavior in early childhood settings. In Handbook of positive behavior support. link

Hemmeter, M. L., Fox, L., & Snyder, P. (2014). Teaching Pyramid Observation Tool (TPOT) for Preschool Classrooms (Research ed.). Brookes. link

Muscott, H. S., Pomerleau, T., & Szczesiul, S. (2009). Large-scale implementation of program-wide positve behavioral interventions and supports in early childhood education programs in New Hampshire (p. 22). link

National Center for Pyramid Model Innovations. (2021). Pyramid model overview. link

Pennsylvania Department of Human Services. (2020). Office of Child Development and Early Learning (OCDEL) COVID-19 provider resources. link

Pennsylvania Positive Behavior Support. (2021). Program-wide positive behavioral support. link

Philadelphia Department of Public Health. (2020). Guidelines for childcare and early childhood education centers: During the COVID-19 pandemic. link

Whitebook, M. (1999).Child care workers: High demand, low wages. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 563(1), 146–161. link