Toddlers are little scientists. They are eager to figure out how everything works. They do this through “experiments.” They might throw a ball to the ground and see that it bounces, then throw a doll to see what it will do. They also learn to use objects as tools—for example, using a stick to try to get an out-of-reach toy. And their growing memory takes on an important role in helping them learn. For example, they imitate what they see others do, even hours or days later. So watch your toddler hold a cell phone up to her ear and have a chat, grab your briefcase and put on your shoes, or even pick up the newspaper and “read” it just like she’s seen you do.

Create lots of chances for your toddler to “test out” the new ideas and concepts she is learning.

Your child will begin using her new physical skills, strength, and coordination to conduct “experiments” on the new ideas and concepts she is learning. She may stack blocks up in a teetery tower just to see how high it can get before she knocks it down. Or she may practice pouring and filling in the bathtub, which requires a steady hand and lots of hand-eye coordination.

You can see how all areas of development are connected when you see your toddler use their physical skills to explore and learn. They dump and fill, pull and push, move things around, throw and gather items, and much more. Your child’s new physical skills help increase her understanding of how things work by giving her the chance to “test out” the new ideas and concepts she is learning. So, if she carefully pours water out of her sippy cup onto the floor, it is not meant to be naughty, but is probably an experiment to see: What will happen if I do this? (Which will in turn help her learn about the use of paper towels…)

What you can do:

- Follow your child’s lead. If your child loves to be active, she will learn about fast and slow, up and down, and over and under as she plays on the playground. If she prefers to explore with her hands, she will learn the same concepts and skills as she builds with blocks or puzzles.

- Offer your toddler lots of tools for experimenting–toys and objects he can shake, bang, open and close, or take apart in some way to see how they work. Explore with water while taking a bath; fill and dump sand, toys, blocks. Take walks and look for new objects to explore—pine cones, acorns, rocks, and leaves. At the supermarket, talk about what items are hard, soft, big, small, etc.

Play pretend!

As your child gets closer to 2, he will take a very big step in his thinking skills as he develops the ability to use his imagination. This means that he can create new ideas and understand symbols. For example, he offers his bear his sippy cup showing he understands that the stuffed bear is a stand in for a real bear who can eat.

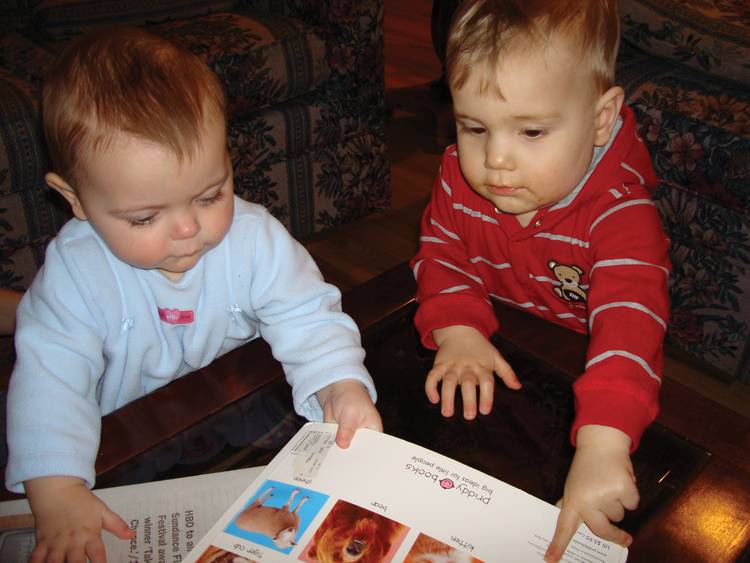

You will see your child’s ability to use his imagination in action as he goes from using objects in they way they are intended to be used–a comb for combing hair–to using them in new, creative ways. The comb might become a toothbrush for a stuffed animal. Other examples of symbolic thinking skills in action would be seeing your toddler hold up a stuffed dog and saying ruff ruff, or babble into a toy phone. He now understands that his stuffed dog is a symbol for a real dog. When he babbles into a toy phone, he understands that this is a “stand-in” for a real phone. Symbolic thinking skills are critical for learning to read as well as for understanding math concepts.

What you can do:

- Play pretend with your toddler. When you see him cuddling his stuffed animal, you might say: “Bear loves it when you cuddle him. Do you think he’s hungry?” Then bring out some pretend food. These kinds of activities will help build your child’s imagination.

- Provide props. Offer your child objects to play with that will help him use his imagination: dress-up clothes, animal figures, dolls, pretend food.

Help your toddler become a good problem-solver

Toddlers can use their thinking and physical skills to solve complex problems by creating and acting on a plan to reach a goal. For example, if they see a toy out of reach, they might climb on a child-safe stool to get it. Or, they might take your hand, walk you to the shelf, and point to what they want.

Your toddler is learning to solve problems when she:

- Tries to flush the toilet

- Explores drawers and cabinets

- Stacks and knocks down blocks

- Pushes buttons on the television remote control or home computer

- Pokes, drops, pushes, pulls and squeezes objects to see what will happen

Being goal oriented also means that toddlers are much less distractible than they may have been earlier. While at 9 months they may have happily turned away from the stereo if shown an interesting rattle, now most toddlers will glance at the rattle and then turn right back to the stereo. Time to do another round of child-proofing!

Your toddler can also solve problems by using her memory to apply ideas to new situations:

- Pull the cover off a toy hidden from view

- Go find the kitchen stool when she wants to reach the countertop

- Blow on her food when you say that her dinner is “hot”

- Try to get her own jacket on

- Use early sharing skills and simple language (with the help of adults) to solve problems with their peers.

What you can do:

- Provide the support your child needs to solve a problem but don’t do it for him. If he’s trying to make a sandcastle but the sand won’t stick, show him how to add water but don’t make the castle for him. The more he does, the more he learns. This builds thinking skills and self-confidence.

- Child-proof your house—again! Get down on your child’s level and explore in all the ways he is able to now. This will help make sure you identify and move all the things he can get to. Doing this helps ensure your child is safe and also reduces the need for lots of No’s.

- Encourage your child to take on some self-care activities—combing hair, brushing teeth, or washing her face. This helps her learn how familiar objects work and solve problems like how to hold the brush.

- Give your child the chance to help around the house. She can wipe down the counter with a towel or sponge, push a broom or mop, rake leaves. These activities give your toddler many chances to solve problems such as how to clean up messes or get rid of the leaves. They also help your toddler feel helpful which builds their self-esteem and self-confidence.

Nurture your toddler’s growing memory

As their memory improves, toddlers are able to remember some past experiences, favorite objects and people. They develop clear preferences about who, what, and how they like things. For example, your toddler may now be able to:

- Show a preference for a favorite clothing item, color, book, toy, or “lovey”.

- Show dislike or disinterest, such as moving away from something scary, like a vacuum cleaner, and then showing a fear of the vacuum some time later, even when it is off.

- Point or gesture to communicate his thoughts and feelings; for example, when given a choice between two boxes of cereal, he may point or reach toward the one he wants.

What you can do:

- Give your child choices. Hold up two different pairs of pajamas and say: “Do you want the rocket ship or the motorcycle pajamas tonight?” Ask your child to pick out which story he wants to hear from a selection of a few books you have chosen.

- Make a “My Day” book. Take pictures of your child doing all her everyday activities: brushing teeth, eating breakfast, playing, napping, going to the park, taking a bath, going to sleep. Snap photos of her with her caregiver or family members, like grandparents, that she is close to. Glue each photo onto a sturdy index card, punch a hole in the corner of each card, and tie securely with a short piece of ribbon. After you talk about each page, ask: What comes next? Your child will come to recognize the people, places, and activities in the book, will begin to anticipate what happens next in her day.

Allow for lots of repetition

Toddlers like to repeat actions over and over again. That’s a good thing because repetition provides the practice children need to master new skills. Repetition also strengthens the connections in the brain that help children learn. Young toddlers are learning through repetition by:

- Asking for their favorite song or story over and over

- Trying to feed you, bite after bite

- Pressing the button on an interesting toy many, many times

- Returning, again and again, to an “off-limits” activity or object—like climbing the stairs

What you can do:

- Follow your child’s lead. Let him do things over and over again (even if you find it tiresome!) He will let you know when he is bored and needs a new challenge. If the activity he wants to repeat is unacceptable to you (like jumping off the couch), offer another, similar activity such as jumping outside or jumping over an obstacle course you make inside using soft pillows.

- Add a new twist. If you child loves pushing buttons over and over again, find other things he can push to make something happen, like the button on a flashlight. This will expand his thinking skills even more as he sees how the same action can have a different outcome based on the object.

Be predictable.

As toddlers identify patterns in their lives, they develop expectations about the world. A child who has always been comforted when she gets a bump is likely to approach her caregiver for a kiss when she falls down. Daily routines, like naptime, bedtime, and mealtime, also help children develop sequencing skills—understanding the order in which events happen– an important literacy and math skill. The added benefit of knowing what to expect is that it helps toddlers feel safe and secure, which makes them feel confident to explore their world.

What you can do:

- Create predictable routines (as much as possible.) For example, bath, books, lullabies, bed. And warn your child about changes. If grandma is picking him up from childcare instead of dad, let your toddler know in advance. This shows you are sensitive to his feelings and helps him prepare for the change.

- Point out the patterns in your child’s life. For example, as you prepare for a trip to the playground: First we fill our bag with toys and snacks. Then we get our coats and shoes on. Then we lock the door behind us. Then we walk to the playground. This also shows your child how to plan and act on a series of steps to reach a goal—an important thinking skill.

Encourage your child to explore how things are similar and different

During this second year, one key way toddlers learn how the world works is by recognizing the features of different objects. This leads to the ability to start to sort and categorize. Toddlers often enjoy grouping objects that look similar, such as all their wooden blocks in one basket and all the plastic blocks in another. Your toddler is categorizing when she:

- Figures out how to fit different shapes into holes or stack rings in the right order

- Sorts objects by color, shape, size or function

- Calls all furry, four-legged animals “dogs” or all men “daddy”

What you can do:

- Make everyday moments chances to categorize. Have your child help with the laundry and put all socks in one pile and shirts in another. Go for a nature walk and collect leaves, pine cones, and rocks in a bag. Then sort them when you get home.

- Involve your toddler in everyday tasks. For example, setting the table together is a matching activity since each family member gets a fork, spoon, napkin, and placemat (save the knives for a grown-up). Help your child put each item on the table. Be sure to thank him and tell him what a big help he is.

What You Can Do to Encourage Your Baby’s Thinking Skills from 12 to 24 Months

Follow your child’s lead.

If your child loves to be active, she will learn about fast and slow, up and down, and over and under as she plays on the playground. If she prefers to explore with her hands, she will learn the same concepts and skills as she builds with blocks or puzzles.

Offer your toddler lots of tools for experimenting

This includes toys and objects he can shake, bang, open and close, or take apart in some way to see how they work. Explore with water while taking a bath; fill and dump sand, toys, blocks. Take walks and look for new objects to explore—pine cones, acorns, rocks, and leaves. At the supermarket, talk about what items are hard, soft, big, small, etc.

Play pretend with your toddler.

When you see him cuddling his stuffed animal, you might say: “Bear loves it when you cuddle him. Do you think he’s hungry?” Then bring out some pretend food. These kinds of activities will help build your child’s imagination.

Provide props.

Offer your child objects to play with that will help him use his imagination: dress-up clothes, animal figures, dolls, pretend food. Provide the support your child needs to solve a problem but don’t do it for him. If he’s trying to make a sandcastle but the sand won’t stick, show him how to add water but don’t make the castle for him. The more he does, the more he learns. This builds thinking skills and self-confidence.

Child-proof your house–again.

Get down on your child’s level and explore in all the ways he is able to now. This will help make sure you identify and move all the things he can get to. Doing this helps ensure your child is safe and also reduces the need for lots of “No’s.”

Encourage your child to take on some self-care activities

Such as combing hair, brushing teeth, or washing her face. This helps her learn how familiar objects work and solve problems like how to hold the brush.

Give your child the chance to help around the house.

She can wipe down the counter with a towel or sponge, push a broom or mop, rake leaves. These activities give your toddler many chances to solve problems: Is the spill all wiped up? How do you pull a leaf bag out of the box for Daddy? They also help your toddler feel helpful which builds their self-esteem and self-confidence.

Give your child choices.

Hold up two different pairs of pajamas and say: “Do you want the rocket ship or the motorcycle pajamas tonight?” Ask your child to pick out which story he wants to hear, from a selection of a few books you have chosen.

Make a “My Day” book.

Take pictures of your child doing all her everyday activities: brushing teeth, eating breakfast, playing, napping, going to the park, taking a bath, going to sleep. Snap photos of her with her caregiver or family members, like grandparents, that she is close to. Glue each photo onto a sturdy index card, punch a hole in the corner of each card, and tie securely with a short piece of ribbon. As you look at each page, ask: “What comes next?” Your child will come to recognize the people, places, and activities in the book, will begin to anticipate what happens next in her day.

Follow your child’s lead.

Let him do things over and over again (even if you find it tiresome!) He will let you know when he is bored and needs a new challenge. If the activity he wants to repeat is unacceptable to you (like jumping off the couch), offer another, similar activity: jumping outside or jumping over an obstacle course you make inside using soft pillows.

Add a new twist.

If you child loves pushing buttons over and over again, find other things he can push to make something happen like the button on a flashlight. This will expand his thinking skills even more as he sees how the same action can have a different outcome based on the object.

Make everyday moments chances to categorize.

Have your child help with the laundry and put all socks in one pile and shirts in another. Go for a nature walk and collect leaves, pine cones, and rocks in a bag. Then sort them when you get home.

Involve your toddler in everyday tasks.

For example, setting the table together is a matching activity since each family member gets a fork, spoon, napkin, and placemat (save the knives for a grown-up). Help your child put each item on the table. Be sure to thank him and tell him what a big help he is.

Parent-Child Activities that Promote Thinking Skills

Create an obstacle course.

Lay out boxes to crawl through, stools to step over, pillows to jump on top of, low tables to slither under. Describe what your child is doing as he goes through the course. This helps him understand these concepts.

Play red light/green light.

Cut two large circles, one from green paper and one from red. Write “stop” on the red and “go” on the green, and glue them (back to back) over a popsicle stick holder. This is your traffic light. Stand where your child has some room to move toward you, such as at the end of a hallway. When the red sign is showing, your child must stop but when she sees green, she can GO. Alternate between red and green. See if your child wants to take a turn being the traffic light.

Build big minds with “big blocks”.

Gather together empty boxes of all sorts—very big (like a packing box), medium-sized (shirt or empty cereal boxes), and very small (like a cardboard jewelry box). Let your child stack, fill, dump and explore these different boxes. Which can he fit inside? Which are the best for stacking? Can he put the big boxes in one pile and the small boxes in another?

Make a puzzle.

Make two copies of a photo of your child. Glue one of the photos to sturdy cardboard and cut it into three simple pieces. Put the puzzle together in front of your child. Show her the uncut photo. Put them side by side. Wait and watch to see what she will do. Eventually, she will touch or move the puzzle. With your guidance and help, is she able to put it back together?

Frequently Asked Questions

My 18-month-old is obsessed with our remote control. Why does she always go back to it, even when I try to distract her with other toys?

Such is the way with toddlers: Their most frustrating behaviors are often both normal and developmentally appropriate. At this age, your child is working very hard to make sense of her world. One of the most important ways she does that is by watching and then imitating what you do. You are her first and most important teacher. She sees you say “thank you” to the grocery clerk so she learns to say “thank you” too. She watches you sweep the floors and she picks up a broom to help. Unfortunately, you can’t turn this desire to imitate on and off. So when your child sees you touching the remote control, she wants to touch it, too. After all, it must be a good thing if you’re doing it!

What do children love electronics so much?

You’ll notice that many toys designed for children this age have features they can explore through touch, such as buttons and raised textures—just like most electronics. However, toddlers almost always prefer to play with the real life objects they see you using which is why they go for remotes, cell phones, etc. Toddlers are learning that to be successful, they need to find out how things work. And electronics make for very interesting props. After all, playing with buttons on the remote offers the exciting possibility that–poof!–the magical machine will come alive. Think of how empowering and exciting this is for your child. But it can also drive you crazy! So now is the time to make sure that all “off-limits” electronics are child-proofed or kept out of the way of little hands. However, be sure to offer your child other objects or toys with buttons and other gadgets that he can make work.

How can I get my toddler to stop going for off-limits objects?

Unfortunately, toddlers simply lack the self-control necessary to resist the wonderful temptation of electronic gadgets and other off-limits items (like shiny picture frames or pointy plugs that fit so nicely into those holes in the wall). While toddlers can understand and respond to words such as “no”, they don’t yet have the self-control to stop their behavior, or to understand the consequences if they don’t. Patience is important, since after telling your toddler 20 times not to play with the remote, chances are she’ll still go for it again. Most children don’t even begin to master controlling their impulses until about age 2 ½.

If the object your child is after isn’t likely to pose a danger to him (such as a remote control–although the batteries are a danger if she puts them into her mouth), the decision of how to set limits is yours. Some parents choose to keep all of these gadgets out of reach and don’t allow their children to touch them until they are older. Or, you could allow your child to use them under your close supervision, such as having your child turn the TV on when you’re planning to watch a show and turning it off when you’re through. This models for your child that there are times when using this equipment is okay and times when it’s not.

What’s most important is that you recognize your child’s needs (learning cause and effect, imitating you) and help her meet them in ways that are acceptable to you.

My father recently died, and I’ve been dealing with it okay, but I’m not sure what to do concerning my 20-month-old. When we go to my parents’ house, she asks for Pop-Pop and we tell her he’s not home. However, I can’t keep doing this. I don’t want her to forget her grand-dad, but how can you explain to a baby that someone has died?

This must be a difficult time as you cope with your own feelings and try to make sense of it all for your young child. Helping her understand what has happened to Pop-Pop is indeed a challenge, as 20-month-olds can’t comprehend the idea of death, or even that they will never see someone again. At the same time, children are very tuned in to the feelings of the important adults in their lives, so it is likely that your child, no matter how well you’re handling your Dad’s death, understands that something sad has happened. It is important that what she is sensing is acknowledged.

Since a 20-month-old can’t understand death, trying to explain it to her would probably cause her more confusion and anxiety. Instead focus on addressing her feelings. What’s most important for your daughter at this time is for you to say something like, “Pop-pop isn’t here. I miss him too.” At this time she won’t be able to understand more.

As your child gets closer to 3, she will likely start to ask questions about what happened to her grandfather. You can then explain that Pop-pop is not coming back; that he died, which means that his body stopped working. Tell her this happens when people are very old or sick and doctors and nurses can’t make their bodies work anymore. You can explain that Pop-pop couldn’t do things like eat or play outside anymore. This gives her a context she can relate to. If she asks whether Pop-pop will ever come back, you should tell her the truth–that he won’t. If your child asks whether you or she or others that she loves will die, you can explain that your bodies are healthy and strong so you are not going to die now.

How should I answer my child’s questions about where her Pop-pop is?

Answer your daughter’s questions based on what you think she can understand. Start with something along the lines of: “Pop-pop isn’t here. I miss him too.” As your child gets older and her questions get more mature, your responses will change accordingly until you feel you are ready to tell her: “Pop-pop died. That means that his body stopped working and the doctors and nurses couldn’t make him better.”

Keep your responses brief. A mistake many parents make is giving more information than their child can process. On the other hand, some parents are tempted not to talk about a deceased person for fear that it will upset the child or themselves. But, of course, avoiding the topic doesn’t make the memories or feelings go away. It just deprives your child of the opportunity to make sense of the experience.

How can I help her keep the memory of her grandfather alive?

When your daughter is old enough, share photos, tell stories, and draw pictures of Pop-Pop. You can also have her do something in your father’s memory. Send off a balloon that says, “I love you”. Or have her help you plant a rose bush, for instance, if her grandfather loved flowers. Reading books about loss can also be very helpful. Some good books include When a Pet Dies by Fred Rogers (Puffin, 1998), When Dinosaurs Die by Laurie Krasny and Marc Brown (Little Brown & Co., 1998), and About Dying by Sara Bonnett Stein (Walker & Co., 1985).

Does my toddler have a “short attention span” because she won’t sit for a story for more than a minute?

It is perfectly normal for toddlers to not sit still very long–period. Most don’t like to stay in one place for long now that they can explore in so many new ways– by running, jumping and climbing. So, an adult’s idea of snuggling on the couch to hear a story may not be the same idea a toddler has for story-time. You may only be able to read or talk about a few pages in a book at a time.

Here are some ways to engage active children in reading:

- Read a book at snack times when your child may be more likely to sit for longer.

- Offer your child a small toy to hold in her hand—such as a squishy ball—to keep her body moving while you read.

- Read in a dramatic fashion, exaggerating your voice and actions. This often keeps toddlers interested.

- Get your child active and moving by encouraging her to join in on familiar phrases or words, act out an action in the story, or find objects on the page. These “activities” can help their attention stay focused.

- Choose stories that have the same word or phrase repeated. The repetition helps toddlers look forward to hearing the familiar phrase again and also develops their memory and language skills. Encourage her to “help” you read when you get to this refrain.

- Try books that invite action on the part of the child, such as pop-up books, touch-and-feel books, and books with flaps and hidden openings for them to explore.