Abstract This article explores the many ways in which states can and are addressing racial equity in problem solving and policymaking. The authors explore national data that make the case for addressing bias and advancing equity in state policy; share strategies and best practices for engaging families and communities; and provide examples of policies that can disrupt and dismantle institutional racism, promote equity, and ensure all babies get a strong start in life.

Ensuring an equitable start for all babies requires understanding the influence of race, ethnicity, and racism in the lives of babies and families. As a result of the longstanding history of systemic racism and marginalization in the United States, babies in communities of color, particularly Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native infants and toddlers, are disproportionately at risk for poorer outcomes in each of ZERO TO THREE’s policy framework domains of well-being that are essential for healthy development—Good Health, Strong Families, and Positive Early Learning Experiences.

The findings of the State of Babies Yearbook: 2021 made clear that, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the youngest children in the US did not have the supports they need to thrive (Keating et al., 2021). An unacceptable number of infants and toddlers—2 in 5—lived in families whose income was inadequate to make ends meet. A concerning proportion, particularly among babies of color, are born preterm or at low birthweight, live in households that lack food security, or lack safe and stable housing. The importance of understanding and addressing these inequities has only been made more evident by the disproportionate impacts of COVID-19.

Examining Equity Through the “State of Babies Yearbook: 2021”

The State of Babies Yearbook: 2021 examined the experience of the nation’s babies and their families and, importantly, substantial disparities and inequities in their experience when examined by race/ethnicity, income, and geographic setting. The 2021 Yearbook was augmented by national data collected through the University of Oregon’s Rapid Assessment of Pandemic Impact on Development in Early Childhood (RAPID-EC) Project during the pandemic to show how the crisis was affecting families with infants and toddlers (Center for Translational Research, 2020). Policymakers and advocates can use the data to identify and advance policies that produce the near-term support and long-term stability babies and families need. The findings of both the State of Babies Yearbook: 2021 and RAPID-EC Project made evident the crisis of material hardship faced by far too many families with young children and the profound effects that economic insecurity has had on their well-being. Deep and longstanding economic inequity in the US, including disparities in wealth due to structural racism, underlies most of the struggles families face. Unfortunately, families with young children are more likely than those with older children to have low income or to live in poverty, creating significant distress during their babies’ critical first 3 years—a period of rapid foundational brain development. Research shows the timing of poverty matters tremendously for long-term development and child outcomes, with early childhood poverty being especially harmful to children’s cognitive, social–emotional, and health outcomes (Black et al., 2020; Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997).

Nationally, nearly 1 in 5 babies in the US (18.6%) live in families with earnings below the federal poverty level—an annual income of $25,750 for a family of four in 2019—that struggle to meet basic needs of food and housing. While this national average is troublesome, when examined by race and ethnicity, significant differences are evident. Black, Hispanic, and Native American babies disproportionately live in families with low income or in poverty, comprising more than half of families in each of these groups. Specifically, the percentages of babies in poverty were highest among American Indian/Alaska Native (39%) and Black infants and toddlers (34.4%), both at or near twice the national average of 18.6%. The poverty rate among Hispanic babies (25.3%) was also higher than the national average.

Deep and longstanding economic inequity in the US, including disparities in wealth due to structural racism, underlies most of the struggles families face. Photo: Lennox Wright/shutterstock

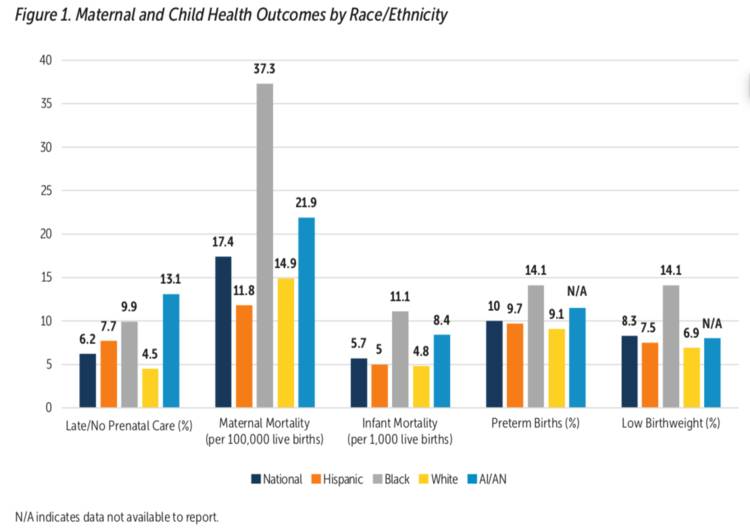

The evidence of substantial disparities—particularly for babies in families of color—are found in maternal health and birth outcomes, such as maternal and infant mortality, low birthweight, and prematurity (see Figure 1). The disparities begin prenatally and require a robust response in national and state policies. Key concerns in the pandemic center on the drop in access to health care among children of color and in families with low income as well as the long-term impacts of high levels of emotional distress among both parents and children.

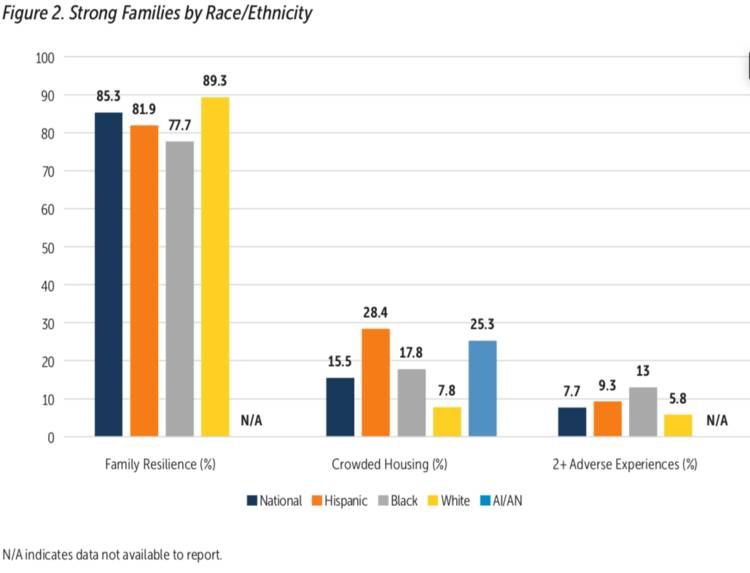

Families with young children face many challenges that can threaten their abilities to meet their children’s basic needs and provide the stable physical environments required for optimal development. Adversities experienced early in life—such as hunger, abuse, neglect, or household instability—can create stress that undermines lifelong development (Shonkoff et al., 2012). A key aspect of Strong Families is economic security and the ability to meet basic needs. Yearbook indicators of state family support policies include home visiting, paid family leave, and paid sick time. Although the Yearbook found that overall family resilience in the face of challenges was at positive levels (85%) pre-COVID-19, the data on resilience and other indicators of family well-being reflect differences by race/ethnicity and income (see Figure 2).

Because more than half of Black, Hispanic, and Native American infants and toddlers live in families with low income or in poverty, many babies of color faced significant challenges even prior to COVID-19, such as crowded housing conditions, adverse early childhood experiences, and experiencing material hardship. The RAPID-EC survey found that food insecurity has increased overall for families with babies and toddlers, and this is especially evident among households with low income and Black and Hispanic households.

Families with young children face many challenges that can threaten their abilities to meet their children’s basic needs and provide the stable physical environments required for optimal development. Photo: Sara Carpenter/shutterstock

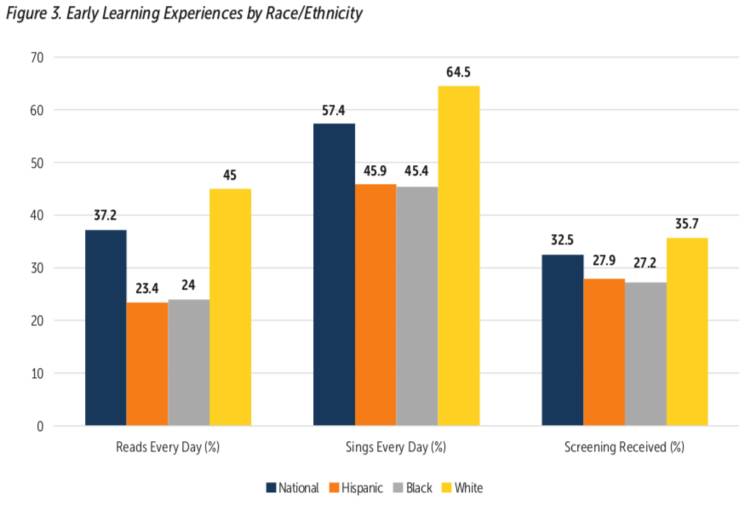

The quality of infant and toddlers’ early learning experiences at home and in other care settings can impact their cognitive and social–emotional development, as well as early literacy. The Yearbook included two indicators of adult–child interaction supporting early language: reading to babies every day; and talking, singing, or telling stories every day. Despite the importance of reading, prior to the pandemic only 37.2% of parents reported reading to their infant or toddler daily. Differences by race and ethnicity as well as by income were found on these indicators, which are likely to be influenced by several factors, such as work schedules, availability of free time, and stress levels (see Figure 3).

The quality of infant and toddlers’ early learning experiences at home and in other care settings can impact their cognitive and social–emotional development, as well as early literacy. Photo: fizkes/shutterstock

Equitable access to high-quality early childhood education can strengthen parents’ interactions with their children in the home learning environment and support parents’ ability to work or attend school. Quality care also can mitigate the negative effects that poverty has on child development and later opportunity in adulthood (Heckman, 2016). However, disparities by income in access to high-quality care are found in many states and communities. Finally, Yearbook indicators addressing early intervention reveal disparities for children of color and with low income, who are at greater risk for delays. Children who receive a developmental screening are more likely to have delays identified, be referred for early intervention, and be determined eligible for early intervention services. Yet, state averages indicate that less than a third of infants and toddlers received a developmental screening.

Thoughtful Collection and Use of Data

The absence of full representation of all babies and families in national and state data limits the extent to which inequities can be fully addressed. Development of policies that advance equity and direct resources where they are most needed requires access to comprehensive data that are collected and reported in a consistent manner across states. Most important, wherever possible, data should be disaggregated by key subgroups at the federal, state, and local levels. It is particularly important that data collection efforts focus on identifying and addressing challenges in reporting on children and families in all racial and ethnic groups, including those for which there has been under-reporting due to smaller population sizes.

Presenting analyses of data by race and ethnicity requires a commitment to equity and the importance of all babies and families’ experiences. The objective in presenting data on disparities is not to present the experience of any group as the norm nor to imply lesser importance of the incidence of negative outcomes within the majority population of White babies and families. Rather, it is to ensure that the experiences of all babies—particularly those in historically overburdened and under-resourced communities—are presented.

Equally important as accurate and consistent collection of data is a deep understanding and ongoing analysis of what the numbers reveal. To do this with equity at the core, interpretation of the data should occur in partnership with those most impacted by the systems and programs being analyzed. Historically, data has been used in ways that did not necessarily benefit communities of color, however, disaggregated quantitative data, when paired with rich qualitative data—gained from families affected by existing policies—can tell a rich story and help to reach truly transformative solutions. These voices are essential in creating strategies that will effectively promote racial and ethnic equity, and these partners should remain at decision-making tables and be encouraged to provide ongoing support and feedback in the implementation of policies and services.

Gathering robust, cross-sector data about early childhood systems continues to be a goal in many states. While guidance exists for individual programs and sectors, reliable collection and analysis remains inconsistent, and disaggregated data, in particular, has proven challenging both to collect and to use effectively in most states.

Advocates and policymakers must persist in collection of accurate disaggregated data at federal, state, and community levels with the ultimate goal of public-facing and accessible dashboards that include downloadable, functional data packages. To ensure that systems and programs are providing necessary supports to all children and families, it is essential to have accurate information on race and ethnicity, and specific data related to age.

Effective communication of disparities is equally important to provide the necessary context for interpretation of the data, with guidance provided in resources such as How to Embed a Racial and Ethnic Perspective in Research (Andrews et al., 2019) and Equitable Research Communication Guidelines (Gross, 2020). Equitable communication of the data allows policymakers and advocates to:

- identify where there is over-representation of babies of a particular race/ethnicity;

- explore the root causes of the inequities and disproportionality where they are revealed;

- examine any areas where disparities by race/ethnicity parallel disparities seen by income and/or urbanicity;

- determine the ways in which past and present policies and practices foster inequities; and

- develop policies that address, reduce, and ultimately eradicate disparities in disproportionately impacted groups as well as negative outcomes in all groups.

It is particularly important that data collection efforts focus on identifying and addressing challenges in reporting on children and families in all racial and ethnic groups, including those for which there has been under-reporting due to smaller population sizes. Photo: DW labs Incorporated/shutterstock

State Spotlight: North Carolina

The North Carolina Early Childhood Foundation Pathways Data Dashboard is the culmination of several years of ongoing collaboration between a diverse group of stakeholders in the state. Members of the group began with a common objective of ensuring that all children in the state achieve 3rd grade reading proficiency outcomes. The effort required consensus on the many factors, both in the home and in the community, that influence a child’s ability to reach this goal. The Measures of Success Framework (Pathways to Grade-Level Reading, n.d.-b) and resulting dashboard (Pathways to Grade-Level Reading, n.d.-a), launched in June 2020, include more than 60 data measures that matter for moving the needle on 3rd grade reading outcomes—from healthy birthweight and safe neighborhoods to positive school climate and trauma-informed communities. The dashboard presents national, state, county, school district, age, income, race, and ethnicity data. It allows anyone who cares about young children and families in North Carolina to have data at their fingertips with interactive graphs and maps to display the data that is of most interest to them.

State Spotlight: Minnesota

In May 2020, The Minnesota Prenatal to Three Coalition (2021) held a virtual convening with four goals in mind:

- learn about new data on infants and toddlers;

- explore how data on infants and toddlers is used to tell stories;

- identify and discuss the negative impact on infants, toddlers and young children when data are missing; and

- learn how to use existing databases to inform policy and planning decisions for infants and toddlers.

Families and providers are the experts in their experiences and the services they use or need to support themselves or the families that they serve. Photo: bbernard/shutterstock

The group wanted to tightly tie data and storytelling together, understanding that it is most often the stories that have not been heard that result in poor policymaking. During the event, representatives from tribal communities encouraged researchers and those who pay for research to think differently about what is typically thought of as “best practice” in data collection: eliminating data that represents less than 1% of the population measured. While this exclusion is meant to protect privacy and remove outliers, when researchers remove data based on this rule, it is possible to lose stories about some minority populations, which often is the case for Native American communities. This convening resulted in a joint venture between Indigenous Visioning and the Coalition, its fiscal host Children’s Defense Fund MN, and lead partners to create a first-of-its-kind data sheet (Minnesota Prenatal to Three Coalition, n.d.) on American Indian infants, toddlers, and young families. To continue the connections between data and stories, advocates have begun the process of journey mapping with families in the state—another effective tool for understanding the real-life experiences of young children and their families.

Centering Family and Provider Voices as an Equity Strategy

Strategies that center family and provider voices are essential to addressing bias and advancing equity in state policy. Families and providers are the experts in their experiences and the services they use or need to support themselves or the families that they serve. They also bring unique power to the policymaking process as constituent voices and in the passion and response they stir in policymakers and the public. Centering their voices results in policies that are more reflective of the needs of children and families and are thereby more effective in addressing the challenges that these policies seek to solve. Centering family and provider voices also has the impact of building the power and capacity of families and communities to advocate on their own behalf in the future, laying the groundwork for a cycle of improved policymaking over time.

Too often, the policymaking process fails to authentically include those who are most directly impacted by policies designed to serve infants, toddlers, and their families. This exclusion both reflects and reinforces current and historical inequities grounded in systemic racism. The implicit assumption undergirding this exclusion is that experts know best what policies families need and that families and the direct service community that work with them most closely are not experts. This concept of expertise and who has it is especially problematic when viewed through the lens of the historic hurdles based upon race, class, and gender placed in the pathways to higher education credentials and other accepted societal markers that define an “expert.” The result is an imbalance of power in the policymaking process between those with positional authority and those most impacted by the policies under consideration. In this context, the explicit and implicit biases of those with more power in the policymaking process have an outsized impact on policy decisions.

Recognizing the expertise of families and direct services providers based on their lived experience and, critically, providing the resources and support to enable them to participate fully in the policymaking process can disrupt this imbalance and result in improved policies for infants, toddlers, and their families. Policy-oriented organizations can play a critical role in eliminating or reducing barriers to full participation by families and direct service providers. These barriers can include very concrete issues such as lack of access to information about policies under consideration and the mechanisms by which they can be influenced, inaccessibility of scheduling wherein policy and advocacy opportunities often take place during business hours when parents and providers are caring for children, language access, or financial barriers associated with things such as lost wages for time spent, transportation, and child care. Less visible but equally important are the intangible barriers such as skills, confidence, and the myriad of subtle cues that signal to families and providers whether they are welcome in the space. Lastly, it is important to recognize and be sensitive to the barriers of time and emotional capacity. Families with young children especially, but also many direct service providers, face a dizzying array of competing priorities to meet the day-to-day needs of their families. This challenge is particularly true for families who are most overburdened and under resourced.

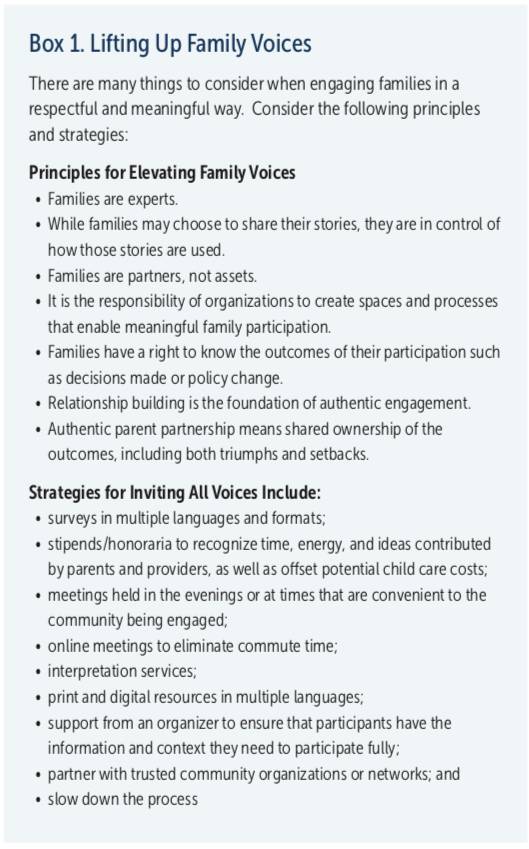

State-based advocacy organizations are exploring creative ways to lift up family and provider voices in state policy (see Box 1). The following vignettes outline ways that three Think BabiesTM (2021) state partners are including and supporting the engagement of families and providers in state policymaking. It is important to note that each of these organizations characterizes their work to center families and providers to advance equity as a work in progress.

State Spotlight: Colorado

In the second half of 2020, Raise Colorado (https://www.raisecolorado.org) implemented the Diverse Colorado Voices (Colorado Children’s Campaign, 2021) virtual listening sessions project in partnership with multiple local birth equity leaders in the state. The series of five listening sessions were held with partners, community members, local leaders, and parents. The goals of the listening sessions were to hear directly from advocates and community members about birth equity, align advocacy efforts with partner organizations, and identify community-led solutions in the perinatal period in Colorado. Recognizing the sensitive nature of the topic, project leads used several strategies to engage and support participants, including engaging local leaders that had deep connections to their communities.

These leaders cohosted the listening sessions, brought a racial justice lens to birth work, and had strong facilitation skills to approach often sensitive conversations and content. Project leads also coordinated with local mental health consultants to offer before and after services to session participants. Participants were also offered the option of one-on-one interviews for those who preferred to share their experiences privately. The listening sessions revealed issues that fell into three major categories: systemic racism, lack of postpartum support, and systems-level inadequacies such as insurance coverage gaps. Listening session participants were engaged in reviewing the resulting report to ensure that it accurately captured their perspectives and recommendations.

The California Dignity in Pregnancy and Childbirth Act contained state reporting requirements to track outcomes for pregnant women. Photo: Andy Dean Photography/shutterstock

The report informed the development of a birth equity bill package under consideration by the Colorado state legislature during the 2021 legislative session and served as an advocacy tool to help advance the legislation. In addition, the project lead sat on the Birth Equity Leadership Committee to advance the bill package. The birth equity bill package is comprised of three bills that integrate the model of midwifery care, create a human rights framework for maternity care, bolster grievance processes for those who experience mistreatment, ensure perinatal support to incarcerated families, expand Medicaid reimbursement up to 1 year postpartum, and disaggregate data by race and ethnicity to address racial inequities in the perinatal period in Colorado.

State Spotlight: Georgia

The Georgia Early Education Alliance for Ready Students (GEEARS) held their annual Strolling ThunderTM event in February 2021. The context of the pandemic has created additional hurdles for families to engage in advocacy while at the same time making it more important than ever that their voices be at the table. Recognizing this, GEEARS approached the event differently than in previous years. Their 2021 Strolling Thunder was held virtually and rather than featuring a rally and day of meetings with policymakers at the state capitol, it included entertainment for infants and toddlers from the Alliance Theatre, a legislative panel, and a letter writing workshop. The workshop provided training and support to help families share their stories and what they want their policymakers to do in writing.

Ensuring an equitable start in life for all babies is a moral imperative and a practical necessity. Photo: paulaphoto/shutterstock

The event was in fact two identical events held at different times (one on a weekday evening and one during the day on a Saturday) to accommodate the differing scheduling needs of families. Materials were mailed to families in advance and a stipend was provided in recognition of their time. In addition to these general approaches to making the event welcoming and supportive for families, GEEARS used targeted strategies to reach families who are most often excluded such as: working with a local Salvation Army to reach several women with infants/toddlers currently experiencing homelessness and working with CDF Action, an organization that supports diverse children and youth in Clarkston, GA, to recruit Arabic- and Amharic-speaking families. Arabic, Amharic, and Spanish simultaneous interpretation was provided to families, and during breakout sessions, the families were placed in virtual meeting rooms with a facilitator who spoke their language. The event’s 71 participants included 10 Arabic-speaking, 9 Amharic-speaking, and 2 Spanish-speaking families. In spite of the challenging fiscal context of the pandemic, Georgia saw increased investments in child care for infants and toddlers as well as other policy advances such as express lane eligibility for Medicaid and creation of a paid leave program for state employees which represents a substantial step forward in the conversation around paid leave in the state.

State Spotlight: New Jersey

Advocates for Children of New Jersey (ACNJ) engaged the Center for the Study of Social Policy in the fall of 2020 to help them assess their efforts and develop intentional plans to ensure racial equity and parent engagement. As part of this process, the 50-member Think Babies NJ coalition was surveyed to assess coalition members’ perceptions of how well the coalition is currently doing in these areas. The results indicated that while coalition members felt that good progress had been made with regard to explicitly focusing on equity in policy conversations, there was room to grow in how the coalition worked with parents. Following review of the results and dialogue with partners, ACNJ has embarked on an effort to move from parent engagement centered around specific, time-limited opportunities for ongoing parent partnership and leadership that centers parents in the policymaking process at every step of the way. In seeking to act on the feedback from the survey and conversations with stakeholders, ACNJ has partnered with Melinated Moms (https://www.melinatedmoms.com), a community-based coalition for women and moms of color, to support the strategy. In the fall of 2020, parents of young children from across New Jersey were recruited to participate in a two-part virtual Find Your Roar advocacy training series to build the capacity of family advocates and build relationships with interested families. Trainings were held in the evenings, and parents were compensated for their time and participation. Graduates of the training series were invited to participate in a Parent Leadership Council which is being designed and co-created with the parent members. The purpose of the council is to provide parents with the opportunity to connect and engage with each other, practice advocacy actions, practice telling their stories, and learn about policy areas of interest to them. Parent voices in New Jersey have already influenced policy outcomes for infants, toddlers, and their families including increased investments in child care, improved paid leave policies, and improvements to infant and early childhood mental health policies. This new phase of the work presents the opportunity to engage parents more deeply as partners and leaders at every stage of the process. An example of this is New Jersey’s 4th annual Strolling Thunder event which took place in June 2021. In addition to engaging parents as participants, this year’s event was co-designed and led by parent leaders.

Policies to Increase Equity

Policy change can occur in multiple ways, via legislative and executive actions or via administrative and organizational practices. Regardless of path, policies should be reviewed regularly along with the data to understand where disparities may occur and where changes and improvements need to be implemented. Other states, like the Think Babies states highlighted previously, have also created highly effective and diverse infant–toddler coalitions, engaging stakeholders across sectors and reaching out to partners to leverage and deploy advocacy resources. Their efforts to improve outcomes by addressing bias and confronting inequities are evident in the policies they have supported and passed.

State Spotlight: Illinois

When Illinois early childhood advocates were invited to join the push for reforms in social equity pillars outlined by the Illinois Legislative Black Caucus, they already had a list of requests that had been waiting for just this opportunity. Thanks to their previous deep thinking about equity in the state early childhood system, their provisions were included in the legislation. In March 2021, Illinois Governor, JB Pritzker, signed the historic legislative package designed to eliminate sources of systemic racism and advance more equitable practices in multiple areas. In total, the bills address health, education, criminal justice reform, and economic development. Provisions of the education bill recognize that policies that improve access to key early childhood services and supports help to ensure equity. In particular, the Education and Workforce Equity Act (Start Early, 2021) established the Infant/Early Childhood Mental Health Consultations Act, which increased the availability of infant/early childhood mental health consultation services in the state and required behavioral health services providers to use DC:0–5TM (ZERO TO THREE, 2016) diagnostic codes for children under 5 years old. In addition, the bill established the Early Childhood Workforce Act which provides targeted supports to those interested in increasing their credentials, while prioritizing diversity of the workforce and communities experiencing the greatest shortages. The bill also extended Part C early intervention services to 3-year-olds until their next school year begins, minimizing gaps in services and increasing continuity of care. Finally, the bill calls for specialized teams, an innovation in service delivery, that will focus on underserved populations—those experiencing homelessness or in the child welfare system, among others. The Illinois Health Care and Human Services Reform Act, the bill reflecting the health pillar, expanded Medicaid to cover doula and home visiting services, enacted a training requirement about trauma for child care providers, and created The Racial Impact note that will allow lawmakers to request an analysis of how proposed legislation may impact people and communities of color. The success of this unexpected and fast-moving legislation speaks to the value of advocates working now to determine where they want to go to create equitable systems for babies and their families, even without a current clear path to move the work forward.

State Spotlight: California

Recognizing the comparatively high rate of maternal mortality for woman of color, the California legislature passed Senate Bill 464, the 2019 California Dignity in Pregnancy and Childbirth Act. The bill mandated implicit bias training for all health care professionals working in perinatal services. The Act also contained state reporting requirements to track outcomes for pregnant women, and it mandated hospitals and birthing centers to provide information on how patients could file discrimination complaints. Finally, a requirement for publication of maternal morbidity and mortality disaggregated by race and other determinants will allow for unprecedented transparency and accountability as the Act is implemented in hospitals across the state. This legislation made California the first state in the US to require implicit bias training for perinatal health care professionals.

Change, fortunately, does not always require legislation. States are often able to advance equity via thoughtful use of existing data sources and modifications to program access and processes. Public leaders in state early childhood systems frequently have the easiest access to data if they exist and can and do use it to make internal decisions in a much timelier manner than when it must travel through legislative processes. In addition, other data exists that can aid state decision making as leaders are pushed to make important decisions regarding equitable distribution of resources and funds.

State Spotlight: Connecticut

When the Connecticut Office of Early Childhood (OEC) learned of imminent federal COVID funding, they were confronted with the same spending and distribution decisions that all states were required to quickly consider as families and child care providers were suffering from the long-lasting pandemic impacts. OEC knew they wanted to be intentional and thoughtful in equitable distribution of the funding to best bolster the child care economy, however, lacking child level enrollment data, they had to look to other data resources accessible to the state in order to reach this goal. Leadership decided that using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) to guide distribution would be a good alternative to previous “equal” distribution of funds that disadvantaged larger programs and didn’t allow for extra support to programs in child care deserts or those serving under-resourced communities. The SVI’s overall vulnerability score is based on variables related to socioeconomic status, household composition and disability, minority status, language and housing type, and transportation, and SVI is highly correlated with the percentage of non-White population within a census tract. The assumption was that by serving programs in areas with the highest SVI, or programs in neighboring communities, funding would make the most impact and be more likely to reach those most in need and result in more equitable distribution than that of previous resources. No one method is perfect—but this process seemed to be the best way to use a variable validated by the census to help stabilize and get funding distributed equitably to communities most heavily impacted by COVID. While the state recognizes limitations in this approach (Connecticut Office of Early Childhood, 2021), it is believed that programs serving children and families with the highest needs were likely to receive more assistance. Connecticut also added additional funds for programs that are high-quality, serve children on subsidy, and serve infants and toddlers.

Conclusion

Ensuring an equitable start in life for all babies is a moral imperative and a practical necessity. State-level policies can disrupt inequities and biases grounded in current and historical systemic racism. Impactful strategies to advance equity require that advocates and state policy leaders adopt an intentional focus on addressing equity and bias at every stage of the policymaking process. Doing so includes thoughtful and intentional inclusion of families in the analysis of data and discussions surrounding policy changes; continuing to strive for accurate and disaggregated data on babies and their families to drive decision making and create an accurate picture of needs and effective solutions; centering the voices of those most impacted in policy creation and implementation; and implementing policies that explicitly seek to advance equity.

Sample Policy Changes That Can Improve Equity

Approaches to advancing equity are limitless. Here are a few strategies to consider as you embark on early childhood systems in your own state.

- Use data to deploy services and resources to communities with the largest disparities.

- Enact strong policies that center on expanding health insurance coverage, embedding child development and family support in primary pediatric care, and building capacity in infant and early childhood mental health.

- Create guidance and structures for all program types to reach and support families that speak a language other than English at home.

- Pass comprehensive paid family and medical leave policies that include all working families with a benefit level that makes taking leave financially feasible.

- Include professional development requirements for training of frontline staff on implicit bias, race, and working with families.

- Increase state investments in Early Head Start and similar programs to ensure that eligible families have access in the communities where they live and work.

- Ensure quality initiatives in child care systems include equity indicators in areas such as curriculum, pedagogy, inclusion, and behavior management.

- Enact legislation that requires bias and equity analysis of policy decisions and legislation at all levels.

Author Bios

Katrina Coburn, MEd, is a senior technical assistance specialist on the State Policy Team at ZERO TO THREE and provides support to states in implementation of ZERO TO THREE’s state policy priorities through technical assistance and facilitation of cross-state learning. Prior to her time on the policy team, Ms. Coburn worked both at the National Center for Development, Teaching and Learning and the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Technical Assistance Coordinating Center at ZERO TO THREE. Her previous experience includes leadership positions in child care both at the state and community levels as well as several years as a family child care provider.

Kim Keating, MEd, is a senior policy research analyst in the ZERO TO THREE Policy Center and is responsible for development of the annual State of Babies Yearbook in partnership with Child Trends. She is co-author with Child Trends of the Yearbook companion briefs Maternal and Child Health Inequities Emerge Even Before Birth and the recently released update, Racism Creates Inequities in Maternal and Child Health, Even Before Birth. Prior to joining ZERO TO THREE, Ms. Keating worked at James Bell Associates for 13 years, where she conducted national evaluations of child welfare programs and provided evaluation training and technical assistance to the diverse set of Administration for Children and Families’ grantees. Previously at Xtria/Ellsworth Associates, she conducted numerous research projects on behalf of the national Office of Head Start and served for 10 years as project manager of the annual Head Start Program Information Report data collection.

Jennifer Jennings-Shaffer, MPA, assistant director of state advocacy at ZERO TO THREE, supports the development and implementation of ZERO TO THREE’s advocacy strategy to move an infant–toddler policy agenda, working primarily to support state-based advocacy campaigns. Ms. Jennings-Shaffer’s previous experience includes serving as the early learning policy director for the Children’s Alliance in Washington state and serving as the Head Start state collaboration office administrator at the Washington State Department of Early Learning.

Suggested Citation

Scott, J. K., Simons, C., Tavassolie, T., Parra, L. J., & Jones Harden, B. (2021). Racial discrimination and parenting: Implications for intervening with African American children and families. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 42(1), 18–25.

References

Andrews, K., Parekh, J., & Peckoo, S. (2019). How to embed a racial and ethnic equity perspective in research: Practical guidance for the research process. Child Trends.

Black, M. M., Hess, C., & Berenson-Howard, J. (2000). Toddlers from low-income families have below normal mental, motor, and behavior scores on the revised Bayley scales. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 21, 655–666.

California Dignity in Pregnancy and Childbirth Act, Senate Bill 464, Ch. 533. (2019).

Center for Translational Neuroscience. (2020). Rapid Assessment of Pandemic Impact on Development Early Childhood Household Survey Project. University of Oregon [dataset].

Colorado Children’s Campaign. (2021). Diverse Colorado Voices report highlights solutions for maternal health.

Connecticut Office of Early Childhood. (2021). Child care program stabilization funding.

Duncan, G. J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1997). The effects of poverty on children. The Future of Children, 7(2), 55-70.

Gross, E. (2020). Equitable research communication guidelines. Child Trends.

Heckman, J. (2016). There’s more to gain by taking a comprehensive approach to early childhood development. The Heckman Equation.

Keating, K., Cole, P., & Schneider, A. (2021). State of babies yearbook: 2021. ZERO TO THREE.

Minnesota Prenatal to Three Coalition. (2021). Early childhood.

Minnesota Prenatal to Three Coalition. (n.d.). American Indians in Minnesota.

Pathways to Grade-Level Reading. (n.d.-a). Data dashboard.

Pathways to Grade-Level Reading. (n.d.-b). Measures of success framework.

Shonkoff, J. P., Garner, A. S., The Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care and Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, Siegel, B. S., Dobbins, M. I., Earls, M. F., McGuinn, L., Pascoe, J., & Wood, D. L. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2663

Start Early. (2021). New Illinois education bill advances racial equity for our youngest learners.

Think Babies. (2021). State partners.

ZERO TO THREE. (2016). DC:0–5TM: Diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood (DC:0–5).