David W. Willis, Center for the Study of Social Policy, Washington, DC

Nichole Paradis, Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health, Southgate, Michigan

Kay Johnson, Johnson Group Consulting, Inc., Vermont

Abstract

Early relational health (ERH) is not a new field, but an enhanced focus on knowledge from infant and early childhood mental health (IECMH), neurodevelopment, and related fields. ERH brings attention to the centrality of safe, stable, and nurturing relationships and resilient communities as drivers for current and future health and well-being of children and families. Responding to the call for an ERH paradigm shift to reprioritize clinical services, rewrite research agendas, and establish new advocacy, the Center for the Study of Social Policy’s National ERH Coordinating Hub works toward health system and community transformation by harnessing networks of stakeholders, families, and professional leaders.

The child health care system in the US is undergoing transformation and adoption of a new paradigm for the promotion of early relational health (ERH). This is a result of many converging forces. Most immediately, the COVID-19 public health emergency, associated economic downturn, and simultaneous reckoning on racial justice focused attention on parents’ capacities to provide safe, stable, and nurturing relationships (SSNRs) and environments for their young children. At the same time, child health providers and other providers of services to young children renewed their focus on the lessons from developmental science about the importance of SSNRs and positive experiences for promoting child health and well-being (Garner et al., 2021). From the field, the calls have grown for adopt ing more advanced, team-based primary child health care; delivering services co-designed with families and communities; and ensuring more equitable, anti-racist, and unbiased services (Garner et al., 2021; Heard-Garris et al., 2021; K. Johnson & Bruner, 2018; T. Johnson, 2020; Liljenquist & Coker, 2021; Peltz et al., 2022; Roubinov et al., 2020; Willis & Eddy, 2022).

Strongly signaling the need for change, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) released an updated policy statement in August 2021 that called for pediatric care to focus on SSNRs to buffer adversity and build resilience. AAP emphasized that pediatric care is on the cusp of a paradigm shift that will reprioritize clinical activities, rewrite research agendas, and realign our collective advocacy (Garner et al., 2021). This updated policy statement focused on promoting relational health in partnership with communities and families had been years in the making, building on leadership from the Harvard Center on the Developing Child and the AAP’s Early Brain and Child Development Initiatives.

By focusing on the safe, stable, and nurturing relationships (SSNRs) that buffer adversity and build resilience, pediatric care is on the cusp of a paradigm shift that could reprioritize clinical activities, rewrite research agendas, and realign our collective advocacy. (Garner et al., 2021)

The Paradigm Shift to ERH

ERH is not a new concept or a new field, but rather an expanded and intentional focus garnered from the knowledge, research, and experience from the fields of infant and early childhood mental health (IECMH), neurodevelopment, and related fields on the primacy of relationships for child development and health. ERH has been an emergent and expanding concept over the last decade, elevating the centrality of positive, nurturing, and stimulating experiences as a key driver of the future health and well-being of children (Frosch et al., 2019; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2004). The term was first conceived by pediatric leaders on the AAP’s Taskforce on Early Brain and Child Development in 2011. Colleen Kraft, a member of the Taskforce leadership team and past president of AAP, noted “that relationships are the new vital signs in pediatrics.” The new term, early relational health, seemed immediately to be an important “sticky idea” that had the power to capture the emerging scientific knowledge of the importance of relationships to future health, development, and well-being, with a focus on promotion and prevention. The new term also seemed to be galvanizing to parents, providers, and policymakers. It frames a new paradigm for promoting health, development, and well-being, starting with early relationships and SSNRs while intentionally focusing on partnering with families. This partnership can become the means for providers to better understand and respond to families’ lived experiences, contextual environments within which families live (including nonmedical determinants of health), and the reality of racist, social economic, and community burdens that may disrupt foundational relationships.

Although ERH seems to be primarily a two-generational and attachment-based concept, it equally emphasizes the simultaneous influences of community resilience and the social, economic, racial, and cultural contexts within which families live (Ellis et al., 2022; FrameWorks Institute, 2020). The foundational relationships that anchor ERH require safe, stable, and nurturing environments for the family, within their social and community context. Changing context is essential to promoting ERH for many families. ERH is influenced and burdened by living in under-resourced communities. Years of intentionally racist and discriminatory policies and practices created such circumstances for many families of color and continue to generate persistent maternal and child health disparities.

This thinking is aligned with the recently described Community Resilience model which also focuses on the importance of the neighborhoods and communities where children and families live (Ellis et al., 2022). The Center for Community Resilience at George Washington University articulation of the Pair of ACEs Tree (Building Community Resilience, n.d.) depicts the interconnectedness of adverse community environments— the soil in which some children’s lives are rooted—and the challenges to early relational health by adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)—the branches that help grow healthy children and families from such roots. The interconnectedness between adverse community and childhood experiences as depicted by The Center for Community Resilience Pair of ACEs Tree serves as a reminder that family-level relational experiences may be negatively influenced by community-level and socio-political factors such as institutionalized and structural racism. Understanding root causes is important. Further, the Pair of ACEs Tree is also a reminder of the importance of creating multitiered solutions in communities that promote better family lives and outcomes. ERH, too, requires good, rich soil to support and foster the growth of positive relational experiences. In short, the Pair of ACEs Tree and community resilience framework encourage all early childhood stakeholders to think not only about addressing individual challenges, but also about enriching community context, changing systems, and fostering equity—the nutrients in the soil—if they wish to advance ERH.

The Centrality of Relationships in IECMH and ERH

ZERO TO THREE defines infant and early childhood mental health as

the developing capacity of a child from birth to five years old to form close and secure adult and peer relationships; experience, manage, and express a full range of emotions; and explore the environment and learn—all in the context of family, community, and culture. Through relationships with parents and other caregivers, infants and toddlers learn what people expect of them and what they can expect of other people. Nurturing, protective, stable, and consistent relationships are essential to young children’s mental health. (ZERO TO THREE Infant Mental Health Task Force Steering Committee, 2001).

This definition obviously overlaps with ERH.

The term IECMH also describes an approach to work with pregnant people, infants, young children, caregivers, and families. IECMH practices are relationship-based, culturally responsive, and trauma-informed (Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health, 2017). IECMH approaches are supported by reflective practices that aid professionals in keeping the baby’s experience at the center of their work (Watson, et al., 2016). IECMH principles are applied across disciplines and service sectors including behavioral health, child welfare, early childhood education, early intervention, health, home visiting, and IECMH consultation. The Diversity-Informed Tenets for Work With Infants, Children, and Families (Thomas et al., 2019) promote IECMH as social justice work defining its critical role in dismantling systems of oppression that impact babies and families.

Early relational health is not a new concept or a new field, but rather an expanded and intentional focus on the primacy of relationships for child development and health. Photo: shutterstock/Lopolo

The presence of the word “infant” in IECMH emphasizes that even newborns experience a full range of human emotions. And although they retrieve memories from infancy differently from memories acquired after language has developed, humans do remember and can be profoundly impacted by their earliest experiences. But what is missing from the term—but not missing from the work—is the emphasis on relationships and the power they hold to buffer or contribute to the earliest adverse experiences.

The field of IECMH encompasses the full continuum of services and supports (i.e., promotion, prevention, and treatment) necessary to promote healthy development, prevent mental health problems, and treat mental health disorders (ZERO TO THREE, 2017). Perhaps because IECMH was born from attachment theory and psychodynamic principles, there are often misconceptions that IECMH is focused solely on the treatment end of the service spectrum. And unfortunately, there remains mental health stigma in some sectors of communities—among parents, providers, policymakers, and other interested groups. In fact, the term, “infant mental health,” remains problematic for some and may be a hindrance for expanding or seeking supports.

ERH is designed to complement and expand the application of IECMH in prevention and promotion scopes of service. Like IECMH, ERH builds from the decades of scientific understandings from neurodevelopment and child development. The use of the term of ERH represents the centrality of relationships between parents and infants. The inclusion of IECMH in broader conversations ensures an intentional focus on the experiences of the infant in the context of their relationships. ERH can open a door in conversations about what babies and families need, and then open it further for more targeted IECMH-informed interventions and increases awareness that infants do, in fact, have mental health.

There is an urgency to promote and protect the needs of infants, young children, and families because of COVID-19 impacts and the multiple stresses on families. ERH responds to the critical need to articulate and expand essential supports and buffering relationships that are key for a public health and societal response (Dozier, 2022). The power of the ERH term can be leveraged to enlist those who seek to impact the lives of babies and families. It can expand an early relational health workforce, and will require, of course, learning from the field of IECMH and its principles (Bruner, 2021).

ERH Coordinating Hub at Center for the Study of Social Policy

In 2019, with the generous support of the Perigee Fund of Seattle, the ERH Coordinating Hub was launched at Center for the Study of Social Policy (CSSP) to focus on advancing ERH by transforming child health care and early childhood system building (see Box 1). This new initiative at CSSP builds on the Pediatric Supporting Parenting (PSP) initiative that included the Fostering Social and Emotional Health Through Pediatric Primary Care: Common Threads Report to Transform Practice and Systems report and other PSP reports about transforming child health care (Cohen-Ross et al., 2019; Doyle et al., 2019; K. Johnson et al., 2020). These reports advanced the national discussion about how to accelerate transformation.

The ERH effort began by establishing partnerships with many stakeholders and leaders in child health, public health, and communities. In addition, the ERH Hub engaged with various early childhood strategic networks providing webinars and discussion groups, and the development of partnerships including Reach Out and Read (ROR), CSSP’s Early Childhood Learning and Innovation Network of Communities, AAP Chapters, early childhood system leaders, Strengthening Families network, home visiting networks, and others. The ERH Hub also staffed and led the National Early Relational Health Advisory Panel that has become a thought leadership group and learning collaborative of more than 30 stakeholders who meet quarterly and advise on the development of a national consensus regarding ERH and the needed action.

Some partnerships have advanced more rapidly and developed into larger efforts to advance the paradigm shift of ERH. ROR supports positive, language-rich parent–child interactions through early literacy promotion strategies across its network of more than 6,400 clinical locations and more than 34,000 medical providers nationwide. The strategic partnership between CSSP and ROR is accelerating ERH transformation. In addition, building on research about the observational elements of emotional connection—the Vital Signs of Early Relational Health as reflected in the Welch Emotional Connection Screen (Hane et al., 2019)—the ROR Next Chapter is a 5-year initiative to explore the integration of the observation and promotion of emotional connection within its evidence-based model in pediatric primary care. ROR will pilot and scale strategies for partnering with families in the dialogue, discussion, and support of their emotional connections, as well as the creation of an expanded pediatric clinical practice of observation and monitoring of ERH to promote optimal development and future well-being. This initiative offers an important opportunity to advance ERH as part of child health care transformation within a network of practitioners ready for the paradigm change.

By 2022, 3 years into the work, the National ERH Initiative at CSSP is contributing to the national movement by bringing strategic network leadership across the early childhood and health sectors in support of the paradigm shift of ERH. Building from the consensus of many, the ERH Hub established its ERH 3.0 Strategic Priorities that guide activities for the next 3–5 years:

- Strategy 1: Parent leadership as a key equity strategy

- Strategy 2: Advancing ERH across place-based early childhood community initiatives

- Strategy 3: Technical assistance resources for communities and providers

- Strategy 4: Multisector and cross-sector workforce development

- Strategy 5: Measurement, research, and evaluation

- Strategy 6: Policy advancement

- Strategy 7: Widespread messaging and dissemination

Listening to the Voices of Families to Advance ERH

Strategy 1 is focused on parent leadership. Listening to the voices of families about their hopes and dreams for their young families and the role that the child health system and family supports services can provide has helped to shape CSSP’s ERH Hub’s efforts from the start. The first inquiries emphasized that families must feel respected, heard, and not judged by a child health practitioner (Center for Improvement of Child and Family Services, 2020). A qualitative study of the family perspectives on ERH was conducted by parent/peer-lead focus groups, with: (1) African American mothers in inner northeast Portland; (2) Spanish-speaking Latinx mothers in rural Oregon; and (3) White mothers in an isolated rural community in southern Oregon. The findings have subsequently informed the equity and family partnership strategies of the ERH Hub.

Parents articulated the value of building strong relationships with their children and seeing their infants holistically from physical to emotional health. They emphasized that emotional support for parents is extremely important and that families tend to find this with trusted friends and family members. Parents noted that when these informal networks were absent, young mothers shared the common experience of the difficulty in finding needed supports.

Years of intentionally racist and discriminatory policies and practices continue to generate persistent maternal and child health disparities. Photo: shutterstock/Rawpixel.com

When it comes to their experiences with health providers, the parents in each of these groups shared that they continue to experience racism, classism, and judgmental attitudes in their relationships with medical providers, and frequently were “not being heard.” They often felt that their health provider was rushed and overly focused on physical health, rather than seeing their families holistically. Many parents were left with a sense of distrust of the medical community, and uncertainty about the role of health providers in supporting ERH. Others expressed a desire or hope that their health providers could be more supportive. Families’ hopes for more supportive and trusted relationships with their health provider signal the need for adopting the ERH paradigm shift and increased effort to reduce provider bias.

The development of trust between health care providers and families is a critical element for the greater achievement of equity, anti-bias, and anti-racism. Accordingly, the CSSP has established an ERH Family Network Collaborative made up of a group of parent leaders who connect to the parent community they represent (their constituencies) and bring that collective voice into this work. The ERH Family Network Collaborative includes parent leaders who bring their lived experience as African Americans, Hispanics, Indigenous tribal members, fathers, peer home visitors, and parents of children with special health care needs. This group will engage other parents in their communities and inform ERH Hub efforts on an ongoing basis. Goals for the ERH Family Network Collaborative include the development of broader networks of parent leaders in support of ERH and the elevation of parent leaders as local, state, and national ambassadors for ERH and equity.

Family-Centered Community Health System

Strategy 2 is to advance ERH across place-based early childhood community initiatives. Advancing ERH will require much greater collaboration between child health systems, public health, communities, and families (Garner et al., 2021). The five “proof point communities” (Durham, NC; Oakland, CA; Onondaga, NY; Pierce County, WA; and UCLA, CA) funded within the PSP Initiative are focused on linking child health systems and communities with family engagement to advance ERH over 4 years. The ERH Hub is involved in this effort.

CSSP has also articulated six elements of an integrated, equitable community and child–family health system, in a Family-Centered Community Health System model to advance ERH (Willis et al., 2020), including:

- a place-based approach for achieving population health with data that informs local decision-making;

- a local, coordinated early childhood system that works to dismantle structural inequities;

- high-performing medical homes that better support families;

- parent leadership networks that hold programs and services systems accountable;

- strategies that support ERH for improved life course outcomes; and

- vibrant and robust family- and community-led networks that support positive experiences for children and families.

This aspirational model leads with parent leadership and power-sharing with programs, services, and communities all in support of those foundational relationships for ERH. As part of Strategy 3 on providing technical assistance and resources, the ERH Hub has designed and tested a new planning tool for early childhood system leaders in communities to map their current cross-system activities in support of a Family-Centered Community Health System and advancing ERH.

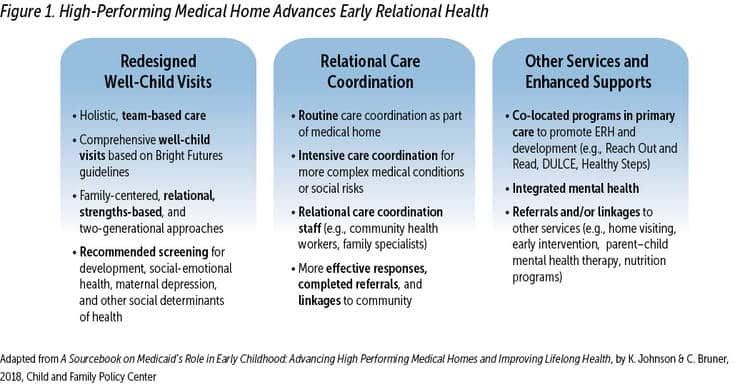

The High-Performing Medical Home Advances ERH

The paradigm shift for child health care will require new forms of clinical practices to advance ERH. Recent descriptions of the “high-performing medical home” distinguishes it from common practices today, which are limited in scope and impact (K. Johnson & Bruner, 2018). To advance the high-performing medical home, and realize the paradigm shift for ERH, will require changes and enhancements to practice design, better financing, and measurement approaches. This effort builds on the AAP’s Bright Futures Guidelines and expands use of advanced team-based care models that allow for relational care coordination and for effective referral, connection, and follow-up with other community resources. Practices can embed such models as HealthySteps and DULCE with a developmental specialist or community health worker who is a member of the medical home team and builds respective and responsive relationships with families to address family resource needs, conduct necessary screening, and ensure effective referrals. These medical homes also embed ROR and integrated behavioral health that includes IECMH best practices. As use of the high-performing medical home and team-based care expand, they will be ready to adopt the new promotion, monitoring, and early identification advancements to advance ERH (see Figure 1).

Building a Relational Health Workforce to Advance ERH

Strategy 4 is focused on multisector and cross-sector workforce development. The relational health workforce includes an array of people whose primary responsibility is to foster relational health, through building relationships of trust and coaching and modeling empathetic and nurturing relationships with children, youth, and families and increasing positive social relationships (Bruner, 2021). The expansion of the relational health workforce is a key strategy for advancing ERH. Health care settings can contribute to a child’s and family’s relational health while recognizing the importance of social connections, supports, and interactions in overall child and family health. This contribution may be through a fully transformed high-performing medical home or one step along the way in transformation. These efforts are designed to enhance family engagement, trust, and partnerships with families and to combat all forms of bias, discrimination, and racism. Policy and program change can support transformation. For example, only a handful of states are using their option to finance community health worker services in Medicaid. Recent policy changes in Washington State will allow for Medicaid payment for community health workers in the pediatric medical home. This innovation is envisioned as a unique opportunity to focus their efforts on supporting the ERH of families by attending to family strengths and assets, identifying family needs, and ensuring connections to local resources. In addition, states such as California, New Jersey, Virginia, and Washington are increasing Medicaid financing and other support for the community perinatal workforce (e.g., birth doulas, home visitors, and lactation specialists). Such efforts offer additional opportunities to emphasize the paradigm shift toward ERH in all training, messaging, and communications with families.

The relational health workforce can be particularly effective in the following ways in ensuring that young children and their families have a strong start:

- Recognizing and articulating to families the importance of foundational relationships of ERH.

- Communicating in that moment of becoming new parents when they are most receptive and eager to learn about most important approaches to the daunting process of parenting, especially when delivered by a workforce of similar lived experiences.

- Supporting and attending to the myriad stresses and distractors that may burden a family and influence ERH.

- Partnering with families in their home offers an opportunity to bring a more trusted and equitable approach to promotion and prevention efforts.

- Earning a credential that documents competency (i.e., that specialized ERH or IECMH knowledge, skills, and experiences have been accrued and inform their work).

The foundational relationships that anchor early relational health require safe, stable, and nurturing environments for the family, within their social and community context. Photo: shutterstock/Lucky Business

HealthConnect One and CSSP are now collaborating on a 24-month project to bring the adoption of ERH training across the HealthConnect One doula and perinatal support networks. This initiative will co-develop and test new ERH training modules with doulas and families across several doula networks, with the goal of offering to all as a standard training as well as to inform future ERH training efforts for additional relational health workforce networks.

Using Measurement and Research to Advance ERH

Strategy 5 focuses on measurement and research. Through partnerships, the ERH Hub has increased the visibility of research, measurement tools, and evidence-based practices. Through meetings, webinars, and a monthly e-newsletter, understanding of the science and its implementation is growing.

A related aim is to monitor knowledge of ERH in the field to understand the impact of Strategy 7 for message dissemination. In 2020, the ERH Hub conducted a survey of the early childhood field about its knowledge of ERH and its current activities (Willis et al., 2020). The survey of almost 600 early childhood service providers (e.g., home visitors, child health practitioners, early childhood system builders, and IECMH specialists) showed broad and surprising prima facie understanding of the term “early relational health.” Among survey respondents, 22% noted that ERH, as a concept, was recognized both explicitly and implicitly even though the term “early relational health” was new and unfamiliar. More important, survey respondents provided a list of evidence-based and well-developed models and services that they understand to advance ERH (see Box 2).

Home Visiting Models and Enhancements

- Healthy Families America (HFA), Parents as Teachers (PAT), Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP)

- Family Connects

- DANCE in NFP, CHEERS in HFA

- Child First

- FAN Training

Parent Education Programs

- Circle of Security-Parenting

- NCAST

- Strengthening Families Framework • VROOM

- Talking Is Teaching

- Play and Learning Strategies (PAL) • Incredible Years

- Growing Great Kids Curriculum

- Lemonade for Life

- Read/Talk/Sing

- MOM Power

- Nurturing Parenting

- Triple P

Early Care and Education Enhancements

- Pyramid Plus approach

- Head Start/Early Head Start • FIND

- Touchpoints

- DIR Training

High-Performing Medical Home Augmentations

- Reach Out and Read

- Promoting First Relationship

- DULCE

- HealthySteps

- Video Interaction Project

- FAN Training

- Early Relational Health screening and video feedback

Source: Adapted from Early Relational Health National Survey; What We’re Learning From the Field, by D. Willis, S. Chavez, L. Jang, P. Hampton, & A. Fine, 2020, Center for the Study of Social Policy.

It is notable that none of the recognized activities and models had been brought to scale. The ERH survey also made visible the importance of equity and the importance of engaging families of color, in particular, in co-design of ERH efforts.

Partnering with families in their home offers an opportunity to bring a more trusted and equitable approach to promotion and prevention efforts. Photo: shutterstock/Prostock-Studio

Policy Implications to Promote ERH

To accelerate the paradigm shift toward ERH will require substantial policy advances. Many different federal and state policies affect the health and well-being of infants, young children, and their families. The current policy climate and recent federal investments in families and communities offer unprecedented opportunities to reimagine health, early care and education, economic, housing, and other family-serving systems to reflect what children and families want and need. In particular, the COVID-era funding in FY 2020–2022 represents new investments in programs, services, and supports that can strengthen families and communities. Now is the time to partner with families and communities to advance equity and strengthen ERH through effective policy advocacy and implementation.

Strategy 6 focuses on advancing policy. The high-level goals of the ERH policy agenda are to:

- Aim to advance equity in design, implementation, and practice of all policies.

- Support family economic security and mobility for two-generation success, including paid family leave; child tax credits; and assistance to address insufficient food, housing, income, and other concrete needs.

- Train the providers serving families in ERH principles and best practices, including anti-racist and anti-bias training approaches.

- Scale up and sustain evidence-based interventions and community system innovations that promote ERH.

- Develop a diverse and well-trained relational workforce to support ERH, including community health workers, doulas, home visitors, and others.

- Advance high-performing medical homes using team-based, family-driven approaches, with relational care coordination.

- Increase access to IECMH services, including promotion, prevention, and treatment for parents and children together.

- Strengthen early childhood systems, with linkages and coordination among health, family support, early care and education, home visiting, early intervention, mental health, housing, child welfare, and other services and informal supports.

Toward the Future

A paradigm shift toward relational health has offered great promise in all early childhood sectors for improving infant, child, and family well-being. The US needs to ensure SSNRs and environments that can surround families and communities with hope, the opportunity to build health, protect from adversity, and heal those suffering from trauma and toxic stress. Focusing on ERH can drive transformation in service delivery, new financing models and policies, and better outcomes for infants, children, and families in this moment and for a lifetime.

Author Bios

David W. Willis, MD, FAAP, serves as a Senior Fellow at the Center for the Study of Social Policy (CSSP) and is a national expert in pediatrics, early childhood systems, and early relational health. At CSSP he helps to advance the growing intersection of child health transformation and early childhood system building with a social justice emphasis and an early relational health frame. Prior to coming to CSSP, Dr. Willis served as the inaugural executive director of the Perigee Fund in Seattle, the division director of Home Visiting and Early Childhood Systems in the Health Resources & Services Administration under the Obama administration, an early brain and child development pediatric leader in Oregon and the American Academy of Pediatrics, and a 30+ year developmental–behavioral pediatric clinician in Portland, Oregon. He received his medical degree from Thomas Jefferson University.

Nichole Paradis, LMSW, IMH-E® (she/her/hers), is the executive director of the Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health (Alliance) working to build and sustain a diverse workforce, informed by infant and early childhood mental health principles, that strengthen early relationships. The Alliance seeks to advance social and economic justice, support professional development and research, and engage Alliances for Infant Mental Health as partners. Ms. Paradis has written and presented extensively about workforce development across all sectors that serve infants, young children, caregivers, and families. Her most recent publication, “The Implementation of a Multi-Level Reflective Consultation Model in a Statewide Infant and Early Childcare Education Professional Development System,” appears in a 2022 volume of the Infant Mental Health Journal.

Kay Johnson, MEd, MPH, is nationally recognized for work on maternal and child health, as an advocate, researcher, and consultant. Reducing the impact of poverty and racism and increasing access to care are lifelong goals. Her expertise encompasses a wide range of policy and program issues. She is currently president of Johnson Group Consulting. Her work at the Children’s Defense Fund, March of Dimes, George Washington University, and Johnson Group helped to shape the direction of MCH and Medicaid policy since 1984. Prior to her policy career, Kay worked with families in early care and education, early intervention, and inclusive child care settings.

Suggested Citation

Willis, D. W., Paradis, N., & Johnson, K. (2022). The paradigm shift to early relational health: A network movement. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 42(4), 22–30.

References

Bruner, C. (2021). Building a relational health workforce for young children: A framework for improving child well-being. InCKMarks. link

Building Community Resilience. (n.d.). Pair of ACEs tree. link

Center for Improvement of Child and Family Services. (2020). My baby, my doctor & me: Hearing from parents about foundational relationships and the role of the health care system in promoting early relational health. Portland State University. link

Cohen-Ross, D., Guyer, J., Lam, A., & Toups, M. (2019). Fostering social emotional health through primary care: A blueprint for leveraging Medicaid and CHIP to finance change. Center for the Study of Social Policy and Manatt Health. link

Doyle, S., Chavez, S., Cohen, S. D., & Morrison, A. A. (2019). Fostering social and emotional health through pediatric primary care: Common threads to transform everyday practice and systems. Center for the Study of Social Policy. link

Dozier, M. (2022). Introduction of pecial section of Infant Mental Health Journal: Meeting the needs of vulnerable infants and families during COVID-19: Moving to a telehealth approach for home visiting implementation and research. Infant Mental Health Journal, 43(1), 140–142. link. link

Ellis, W., Dietz, W., & Chen, K. L., (2022). Community resilience: A dynamic model for public health 3.0. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 28(Suppl 1). link. link

FrameWorks Institute. (2020). Building relationships: Framing early relational health. link

Frosch, C., Schoppe-Sullivan, S, & O’Banion, D. (2019). Parenting and child development: A relational health perspective. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 19(4). link. link

Garner, A., Yogman, M., Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Fmaily Health, Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, & Council on Early Child. (2021). Preventing childhood toxic stress: Partnering with families and communities to promote relational health. Pediatrics, 148(2), e2021052582. link

Hagan, J., Shaw, J. S., & Duncan, P. M. (Eds.). (2017). Bright Futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children and adolescents (4th ed.). American Academy of Pediatrics.

Hane, A. A., LaCoursiere, J. N., Mitsuyama, M., Wieman, S., Ludwig, R. J., Kwon, K. Y., Browne, J. V., Austin, J., Myers, M. M., & Welch, M. G. (2019). The Welch Emotional Connection Screen: Validation of a brief mother– infant relational health screen. Acta Paediatrica, 108(4), 615–625. [link] (https:// doi.org/10.1111/apa.14483). link

Heard-Garris, N., Boyd, R., Kan, K., Perez-Cardona, L., Heard, N. J., & Johnson, T. J. (2021). Structuring poverty: How racism shapes child poverty and child and adolescent health. Academic Pediatrics, 21(8S), S108–S116. link. link

Johnson, K., & Bruner, C. (2018). A sourcebook on Medicaid’s role in early childhood: Advancing high performing medical homes and improving lifelong health. Child and Family Policy Center. link

Johnson, K., Willis, D., & Doyle, S. (2020). Guide to leveraging Title V and Medicaid to promote social-emotional development. Center for the Study of Social Policy and Johnson Group Consulting, Inc. link

Johnson, T. (2020). Intersection of bias, structural racism, and social determinants with health care inequities. Pediatrics, 146(2). link. link

Liljenquist, K., & Coker, T. R. (2021). Transforming well-child care to meet the needs of families at the intersection of racism and poverty. Academic Pediatrics, 21(8S), S102–S107. link. link

Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health. (2017). Competency guidelines: Endorsement for culturally sensitive, relationship-focused practice promoting infant and early childhood mental health.

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2004). Working paper #1: Young children develop in an environment of relationships. link

Peltz, A., Wong, C. A., & Garg, A. (2022). Promoting child health equity through Medicaid innovation. Pediatric Annals, 51(3), e118–e122. link. link

Roubinov, D., Bush, N., & Boyce, T. (2020). How a pandemic could advance the science of adversity. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(12) link. link

Thomas, K., Noroña, C. R., & St. John, M. S. (2019). Cross-sector allies together in the struggle for social justice: Diversity-informed tenets for work with infants, children, and families. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 39(3), 44–54.

Watson, C. L., Harrison, M., Hennes, J., & Harris, M. (2016). Revealing “the space between”: Creating an observation scale to understand infant mental health reflective supervision. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 37(2), 14–21.

Willis, D., Chavez, S., Jang, L., Hampton, P, & Fine, A. (2020). Early Relational Health National Survey: What we’re learning from the field. Center for the Study of Social Policy. link

Willis, D., & Eddy, M. (2022). Early relational health: Innovations in child health for promotion, screening and research. Special section on early relational health. Infant Mental Health Journal. link. link

ZERO TO THREE. (2017). The basics of infant and early childhood mental health: A briefing paper.

ZERO TO THREE Infant Mental Health Task Force Steering Committee. (2001). Definition of infant mental health [Internal report].