Raquel Munarriz Diaz and Tiffany Taylor-Jones, University of Florida Lastinger Center

Abstract

A community of practice (CoP) is a vehicle for bringing in participants who share a common interest to learn from and grow with each other. In order to have a transformative learning experience, the CoP needs to be facilitated by a humble, credible facilitator. This article examines the role and benefits of a humble, credible facilitator and how these characteristics are necessary for engaging powerful interactions.

“How you are is as important as what you do” is a ZERO TO THREE guiding principle that helps explain the imperative role of a community of practice (CoP) facilitator. A CoP is a vehicle for bringing in participants to learn from and grow with each other. It has four major considerations: content, process, structure, and conditions. Through engaging in CoPs, participants grow in community and learn skills they can take to their respective work contexts. Beyond the CoP, the role of the facilitator is key (CoP is the what; the role of the facilitator is the how). To have a transformative learning experience, the CoP needs to be facilitated by a humble, credible facilitator. The facilitator needs to be aware of the content, yet also be open to provide the participants the space and tools to learn from each other. Combining CoPs with a humble, credible facilitator will lead to learning experiences where there is equity of voice, increased engagement, and professional growth.

Setting the Stage: What Just Happened Here?

A well-prepared facilitator packed up from a 3-day CoP Institute, where she began with equal parts nervousness and excitement about sharing the content of the sessions. She now stood exhilarated and exhausted, but she was also feeling something else. She was aware there was more at work here than just powerful content and professional connections. She reviewed each session in her mind. The goals of this institute were to use tools and processes of a CoP to teach about the elements of a CoP: content, process, structure, and conditions, and the role of the facilitator. Essentially the goal was to learn about CoP, while experiencing a CoP!

As a part of the facilitator’s debrief routine, she reflected on the sessions. Developed a powerful agenda….check. Prepped for the session….check. Facilitated the agenda…..check. Experienced powerful transformation…..check? Moving from a session as a facilitator typically included a debrief of these pieces and at least three other considerations:

- Did the agenda meet or exceed the session goals?

- Did the experience transform the knowledge, practice, and reflection of the participants?

- Did the facilitator execute a powerful learning opportunity by offering rigorous content, a collaborative structure, processes that foster equity of voice from the participants, and a safe, empowering space?

Leaving this particular CoP Institute, the facilitator began to wonder, what happened in these sessions, specifically? Why did this experience and others she experienced recently feel so different from the previous professional development she had experienced; so much more transformative? She thought about all of the questions and was still struggling to put her finger on that most impactful element. She continued to explore what it was that had developed a group of early learning professionals into cohesive, collaborative, solutions-oriented, risk takers dedicated to plugging back into the mission in the work, despite challenges, and ready to move toward all the positive possibilities ahead.

Her sustained inquiry led to a review of written reflections from the session participants. She completed a text rendering of the participant reviews. A text rendering is a School Reform Initiative (SRI) protocol in which the readers pull words and phrases from text that resonate with them (SRI, 2014).

Through the text rendering, the facilitator saw words like “challenge, listen, think deeply, power of peers, way of work, equity of voice, job-embedded practice, building cohesion, collaboration, learning, practitioners, safety, facilitator vs. trainer, agreements, protocols, partnership, knowledge, heart, reality, trust, and brave space.” She knew these words individually meant something but collectively she began to unpack what the professional power of these words might have created in this learning session.

A part of that unpacking connected her to a professional learning experience she had participated in at least 3 years before this current experience. The facilitator in that session had offered an in-depth look at the dispositions and skills a successful facilitator offers to their learners. She shared an example emphasizing that the way individuals show up in spaces has a significant impact on the experience of everyone around them. She offered the wisdom that coming into a space with knowledge of the content is essential. The facilitator’s experiences, credentials, and background drive one side of the positive outcomes in professional learning. It offers credibility to the participants and allows the facilitator to stand in their ability to influence the knowledge and practice of others. In simple terms, the facilitator knows a little something about the subject matter and is equipped to share it with others!

But there was something else, too. The facilitator also needed to show up with authentic humility. This humility centers a facilitator in the awareness that a learning partnership is being cultivated, where the learning environment will foster a symbiotic learning relationship. This symbiosis means that the participants will learn and grow, and so will the facilitator, simply through collaborative learning in the sessions. The facilitator shows up with subject matter expertise and stands firm in the reality that they also still have much to learn. This humility fosters a partnership where content drives the professional learning experience but does not dominate it. In this partnership, participants and facilitators bring knowledge and experience to share and then move forward in inquiry, new learning, research, and improved practice and outcomes, together.

Together these two attributes—humble credibility—began to surface as one of the most essential elements to ensure productive learning. Was this beginning to describe what happened? Was this humble credibility surfacing as the most impactful disposition or element of the positive outcomes with the last professional learning facilitation? But what does the term humble credibility even mean? Where does it build from? How do facilitators deploy it, and how does it affect work in early learning? Before we begin to unpack the term humble credibility, let’s first explore what is a CoP.

What Is a CoP?

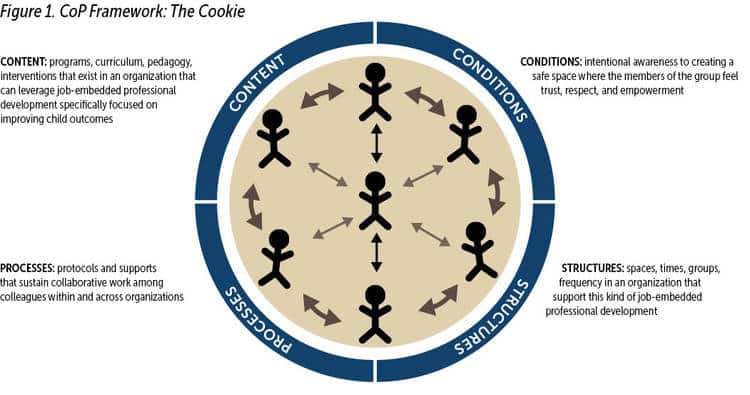

Think of a time when you were a part of a highly productive professional learning experience. What made that experience so powerful? Was it because the content was a topic you were passionate about? Was the experience structured in a way that provided engagement and collaboration? Did the facilitator ensure the group had the conditions of trust and safety? The authors are CoP facilitators. A CoP is defined as “groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis” (Wenger et al., 2002, p. 4). A CoP is collaborative and job-embedded. To be successful it needs to have four considerations: content, process, structure, and conditions (Diaz et al., 2021). (See Figure 1.)

Content is the “passion” that has brought the group together. Is it a curriculum, a topic, a concern? In a CoP, participants discuss topics that are within their realm of control. Challenges are surfaced and categorized as proximal (within the realm of control) or distal (beyond one’s realm of control). In order to have a productive learning experience, time should be spent on unpacking proximal topics and establishing some action steps to take back to one’s practice.

Process consists of intentional, structured protocols to engage the CoP participants while ensuring equity of voice and engagement. Sharing wisdom is a key element of a CoP. Participants engage with each other, to learn from each other to improve their practice. Protocols are key to structure these conversations (SRI, 2017).

Structure. In order to have a highly productive CoP, facilitators are intentional about the structure of the sessions. CoP facilitators take special care in considering the space, time, and groupings during a CoP session. Just like young children, adults also benefit from structure, routines, and rituals.

Conditions. CoP participants need to feel supported in order to make their practice public—requesting, receiving, and offering critical feedback defines the core of a CoP. Facilitators are key in establishing the conditions of trust and safety in order for the group to engage authentically in topics of interest. Special attention is placed on establishing norms that the group define as key to ensure a safe, productive, learning environment.

Let’s return to the story at the start of this article. This facilitator’s agenda was full of powerful articles, new learnings, and experiences that would explore and encourage practice of the four elements of CoP and highlight the integral role of the facilitator. The content of the CoP Institute would be centered around the CoP Framework, the skills and dispositions that distinguish a facilitator from a trainer, and initial preparation for agenda design. The content would be processed with protocols to allow for sharing of practice success and struggle, and to ensure equity of voice in dialogue. These intentional protocols and processes were strategically paired with specific content to build and sustain a collaborative learning environment that prepared participants for the job-embedded practice opportunities ahead of them. The facilitator considered how she determined the structure of the group of attendees to include whole group experiences, small group conversations, opportunities to work in pairs, and lots of debriefs of both the content and process implications. The days were long but moved quickly, and the group was growing closer and closer with each piece of the agenda. The 3 days had built strong conditions of both willingness to consider new strategies and courage to discuss individual elements of professional practice in a way that was really beginning to benefit everyone in the room. Holding space and creating the container for making practices public was beginning to impact each participant’s experience. So, the facilitator continued to reflect on what was influencing the impact of these sessions.

The Role of CoP Facilitator

Beyond the four major considerations needed for a highly productive CoP, the role of the facilitator is key. The facilitator plays a key role in designing, implementing, and reflecting on the learning event or meeting. The learning of the group, logistics of the meeting, and longevity of the work are top of mind for the facilitator (Allen & Blythe, 2004). What is the topic that participants are passionate about (content)? When and where, will the group meet (structure)? What protocols will be used to ensure participant voice is invited and heard (process)? And how will the facilitator ensure the group feels safe to share their wisdom and make their practice public (conditions)?

Facilitators differ from trainers. Trainers are focused on providing information to the group and direct learning, whereas facilitators guide the participants to share their wisdom and use the group’s cues to guide the conversations (Killion & Simmons, 1992). Both trainers and facilitators are knowledgeable in adult learning principles and in the session’s content. The difference is that the facilitator guides the group to provide their knowledge, skills, and experience as part of the learning event. Neither role is better; both serve a purpose in improving professional practice and in guiding productive conversations.

Three characteristics of a skilled facilitator include reading the group, responding, and reflecting (Allen & Blythe, 2004). Reading the group requires the facilitator to be actively listening and observing the group. This constant monitoring of the group helps ensure the group is receiving what they need to have a productive session. Skilled facilitators may also confirm their reading with the group and ask the group to confirm their “read.” Responding includes: “What if anything should I do?” (p. 40). Is there a specific challenge to address or an opportunity to take advantage of? Sometimes no response is also appropriate. Facilitators are constantly thinking on their feet and ensuring the group is guiding the momentum.

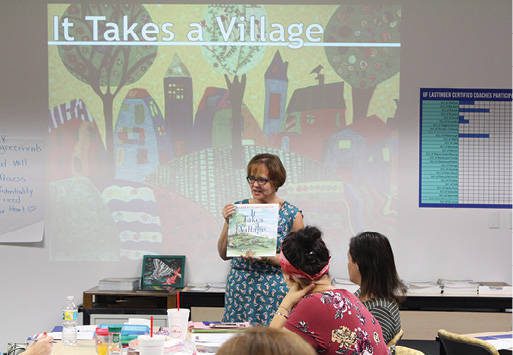

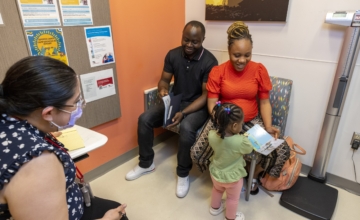

Humility fosters a partnership where content drives the professional learning experience but does not dominate it. Photo courtesy of University of Florida Lastinger Center

Finally, facilitators are constantly reflecting on the entire session. They focus on what went well and what could have been better. Facilitators are lifelong learners and realize they can always find opportunities to grow in their craft and grow in their knowledge acquisition. One of the authors uses the metaphor of a couple dancing together to describe her role as a facilitator. Traditionally, one partner leads the dance and the steps, but the other partner ensures each step is carried with grace and every now and then inserts a few moves of their own. The seamless dance results in a beautiful display of synergy and mutual appreciation. Facilitators and the participants are in a dance to ensure positive outcomes as well.

The Humble, Credible Facilitator

Humble credibility shows up in a facilitator simply within their way of being. In order to make visible what is sometimes unseen, unnoticed, or unnamed, let’s try to intentionally notice what this looks like in action.

Credibility may be easier to define and can be seen when a facilitator begins to share content and information that takes participants from where they are to the next step in a learning journey. Their credibility is evidenced in their “knowing” of the subject matter balanced with their real-life experiences and application of the content. Participants see the cognitive knowing and understanding of content and grow from the facilitator’s sharing of this content. Experiences are shared by the facilitator that validate the new learning in ways that build connections for the learners and leave them wanting to practice or learn more.

The humility in the humble credibility disposition sometimes is not as easily named or noticed. Some people have been socialized that humility or being humble is “passive, submissive, or insecure” (Boss, 2021). Authentic humility, however, does not include these attributes at all. In truth, the facilitator is only one part of the learning whole. Participants themselves bring wisdom and life experience to a community of practice.

Humility allows facilitators to notice others, to affirm what they offer to the experience, and to determine what they need and, in fact, deserve, during the learning event to make the most transformation. A Forbes article defined 13 habits of humble people to include being “situationally aware, retaining relationships, making difficult decisions with ease, putting others first, listening, centering curiosity, speaking their minds, saying thank you, having an abundance mentality, accepting feedback, assuming responsibility, and asking for help” (Boss, 2021). The synergy of these habits allows a humble individual to think and learn better. The humble facilitator’s use of these habits models this style of thinking and learning for the participants as well leading to the benefits being paid forward to others. Humility is a natural disposition for some, but many of the habits of the humble person can be practiced and learned by anyone. Participating in a professional development session with a humble facilitator feels like the participants can show up where and as they are, ready to take the next step forward in the learning journey and willing to try something new.

The combination of humble credibility builds a leader that can move people, with support, toward their goals. This way of being also influences the outcomes of any professional learning experience by inspiring curiosity in new strategies, cultivating openness to listening and practicing new ways of work, and leading to collaboration and flexibility in building mutually beneficial learning partnerships.

The Benefits of a Humble, Credible Facilitator

When groups are working as a CoP facilitated by a humble, credible leader, there are many benefits. These include equity of voice, increased engagement, and professional growth.

- Equity of voice. Through the use of protocols, equity is ensured. Protocols are unique to the CoP framework in that they provide guidelines and boundaries for dialogue (Allen & Blythe, 2004; SRI, 2014). Protocols include time for all participants to share their thoughts, reflect, and clarify as needed. Protocols invite input and create a space for all voices to be heard. This differs from typical discussions, where one voice may be overshadowed or dominated by a few members of the group. One norm that a humble facilitator presents to ensure equity of voice is “Step up; or Step back.” The humble, credible facilitator asks participants to reflect on whether they are dominating the space or need to stretch beyond their comfort zone and speak into the space. Through the protocols (process) and setting of norms (conditions), the stage is set to ensure every participant is invited into the dialogue.

- Increased engagement. A CoP by its nature is a vehicle that supports active participation. Desimone (2011) has identified core features for productive, adult learning which include: (a) content-focused, (b) active learning, © coherence, (d) duration, and (e) collective participation. The role of the facilitator is key in ensuring all these elements are met. The credible facilitator is aware of the content to bring and how that content is coherent to current trends and standards. The humble facilitator puts great care in creating spaces where the participants are active and participating. When the humble facilitator is supporting professional learning, members of the group want to continue to meet and learn from each other (duration). In short, a humble, credible facilitator is naturally inserting the core features into all their adult learning opportunities, including internal meetings. Every time a group of peers are brought together by a humble, credible facilitator, there is buy-in and engagement from the members.

- Professional growth. A growth mindset ensures people are continuously learning. Humans are lifelong learners and benefit from the wisdom of each other. CoPs ensure learning from each other. Members leave with new ideas that they can immediately apply in their own contexts. Issues discussed are relevant and proximal to the participants, hence the job-embedded nature of CoPs lead to improved outcomes at work (Diaz et al., 2021). The role of the facilitators is to welcome the learning from the group and share their wisdom as well.

Conclusion

We work in an innovation center focused on professional development. In March 2020, the world was shaken and the way work was done was instantly changed. As an organization, we ensured we provided a space for people to gather and make their concerns public and share the ways they were (re)learning how to do their work. The teams that remained highly productive were the ones where leadership embraced a humble, credible mindset. These leaders came to each meeting with empathy, care, and grace. They modeled self-care and invited voice from each team member. These leaders knew the wisdom needed would surface from the power of collaboration. In the meetings, the leader would also share their wisdom and work in parallel with their team. The term humble credibility was coined in these challenging times and it has become a way for the organization to do its work internally and with external partners. How can one work toward humble credibility? How can one learn to trust the power of the group’s wisdom to guide growth? The first step is to acknowledge the transformative role of the facilitator—the humble, credible facilitator.

The facilitator considered how she determined the structure of the group of attendees to include whole group experiences, small group conversations, opportunities to work in pairs, and lots of debriefs of both the content and process implications. Photo courtesy of University of Florida Lastinger Center

Author Bios

Raquel Munarriz Diaz, EdD, has more than 30 years of experience working in early childhood education. She is National Board Certified in Early Childhood. Prior to her appointment as professor in residence for the University of Florida in 2009 where she supported teachers earning graduate degrees, Dr. Diaz served as the Miami Science Museum’s project coordinator where she helped develop and disseminate an early childhood science curriculum. Currently, Dr. Diaz is the senior partnership manager at the University of Florida Lastinger Center for Learning. Her current role has her highly involved in seeking partnership opportunities with organizations and early learning state systems who believe in supporting the design and facilitation of reflective, job-embedded professional development for educators. Her passion is focused on cultivating communities of practice in which professionals are empowered to grow in their field through collaborative tools. Dr. Diaz serves as an alumni member of the ZERO TO THREE Fellowship, chair elect of the National Association for the Education of Young Children Affiliate Advisory Board, and member at large for the Florida Association for the Education of Young Children. Dr. Diaz is a first-generation college graduate who strives to inspire the workforce to help themselves and young learners thrive.

Tiffany Taylor-Jones, MEd, is an early learning implementation coordinator with the University of Florida Lastinger Center for Learning. After earning her undergraduate degree from the University of Florida, she continued in her credential attainment by earning her master’s degree in elementary education, and National Board Certification in Early Childhood. Ms. Taylor-Jones served the field of education as a classroom teacher and district level professional development facilitator with Brevard Public Schools. In her current role as an early learning implementation coordinator, she supports online instructors in the Flamingo Early Learning Professional Development System within the Lastinger Center. Her role includes facilitating professional development for online instructors across the nation and support of facilitation around job-embedded professional development strategies including communities of practice and coaching. Ms. Taylor-Jones is a lifelong learner, and her work is grounded in strong early childhood foundations, implementation of tools and processes that enhance collaboration, and a passion for fostering equity in all areas of teaching and learning. She has facilitated at local, state, and national conferences, sharing her work, experiences, and learning with others.

Suggested Citation

Diaz, R. M., & Taylor-Jones, T. (2022). Humble credibility: The role of the facilitator to engage powerful interactions within a community of practice. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 42(4), 49–54.

References

Allen, D., & Blythe, T. (2004). The facilitator’s book of questions: Tools for looking together at student and teacher work. Teachers College Press.

Boss, J. (2021, December 10). 13 habits of humble people. Forbes.

Desimone, L. M. (2011). A primer on effective professional development. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(6), 68–71.

Diaz, R. M., Poekert, P. E., & Bermudez, P. R. (2021). “The Cookie”: A recipe for effective collaboration through communities of practice. Practice. DOI: 10.1080/25783858.2021.1886835.

Killion, J. P., & Simmons, L. A. (1992). The Zen of facilitation. Journal of Staff Development, 13(3), 2–5.

School Reform Initiative. (2014). School reform initiative: Resource and protocol book.

School Reform Initiative. (2017). Why protocols.

Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. M. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice. Harvard Business School Press.