Christopher Watson, Minneapolis, Minnesota

with Maren Harris, Mendota Heights, Minnesota

Jill Hennes, St. Paul, Minnesota

Mary Harrison, Washburn Center for Children, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Alyssa Meuwissen, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities

Editor’s Note

The following article is excerpted and adapted from the RIOSTM Guide for Reflective Supervision and Consultation in the Infant and Early Childhood Field (ZERO TO THREE, 2022). The RIOS is a tool for understanding and evaluating the reflective processes in a supervision session.

The Reflective Interaction Observation Scale (RIOS™) was developed as a research tool to identify the extent to which a supervisory session demonstrates a reflective process grounded in infant and early childhood mental health (IECMH) principles1 and practice. It is aligned with the competencies of the Endorsement for Culturally Sensitive, Relationship-Focused Practice Promoting Infant Mental Health® supported by the Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health, and it has shown initial evidence of validity and reliability (Meuwissen & Watson, 2021). Specifically, the RIOS is applicable to IECMH-informed reflective supervision/consultation (RS/C) that is based in developmental and attachment theory, trauma-informed practice2, and attention to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). It is supported by the rapidly growing body of research exploring interpersonal neuroscience (Bowlby, 1969/1982; Siegel, 2012; Siegel & Shamoon-Shahnok, 2010; Sroufe, 1996; Sroufe et al., 2005). The RIOS describes the content and characteristics of the interactions between the RS/C participants. The focus is not specifically on either the supervisor or supervisee(s) but rather on “the space between” them, what they attend to, and how they interact (Watson, Harrison, et al., 2016). It is not about judging any participant but rather about understanding the nature of their work together.

Although the RIOS was initially developed for research, as those working in the field learned about it they found value in (a) using the RIOS framework to train others in RS/C and (b) applying it to and assessing their own RS/C practice. The RIOS is a structure to describe elements of RS/C rather than to prescribe a specific process of implementing RS/C. There are many different ways in which supervisors conduct individual or group RS/C. Heller and Gilkerson (2009) and Heffron and Murch (2010) have provided guidance regarding the process of initiating and conducting RS/C sessions. The RIOS focuses on the nature of the interactions and the content of the conversations within any given reflective session.

1 The basic beliefs/core principles of infant mental health are the foundation for practice (Stinson et al., 2000). They “help specialists understand their role, cherish each encounter with young children and caregivers, think deeply about the meaning that each interaction has for the infant and the parent, and plan interventions in partnership with families” (Deborah Weatherston, as cited in Shirilla & Weatherston, 2002, p. 4).

2 “A program, organization, or system that is trauma-informed realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery; recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system; and responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices, and seeks to actively resist re-traumatization” (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014, p. 9).

Looking Back to Move Forward

Reflective supervision is part of the broader umbrella of reflective practice, which encompasses a variety of theoretical, discipline, and practice traditions. Reflective practice in this context refers to a way of embedding reflective principles in any professional’s daily work. Use of reflection has been a part of training and practice in a number of fields. Rai (2006) suggested that “reflective practice in all but name has been a cornerstone of social work education since its early psychotherapeutic roots, in which understanding and use of self were integral to practice learning” (p. 787). The use of reflective practice in the fields of education, nursing, and occupational therapy can be traced back to Dewey (1933) in his pivotal work How We Think. Dewey argued that learning is neither passive nor linear, depends on both the context of the event and the learner’s experience, and involves the whole person, including one’s emotions. Later on, Schön (1987) had a significant impact on teacher education, noting that teachers face unique and complex situations every day that cannot be solved by rational solutions alone. He suggested that professional learning could be augmented by reflection. Smyth (1989) concluded that teachers need to address meaning and their own personal journeys to becoming who they are to propel them into making positive changes in their work. The work of these pioneers and others forms the basis of RS/C, to which IECMH practitioners have added an even greater emphasis on relational and emotional experiences of all those involved in service provision: infants and young children, caregivers, and professionals.

As increasing numbers of professionals, programs, and service systems adopt RS/C, inquiry into this unique form of professional development has deepened. Likewise, standards of quality, including guidelines for effective RS/C with groups via virtual technology (McCormick et al., 2020), and endorsement systems for RS/C have been developed.3 All these efforts have increased our understanding of the unique qualities and powerful impact of RS/C in the infant and early childhood field.

3 For more information regarding endorsement in IECMH, see Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health (2020), California Association for Infant Mental Health (n.d.), and Illinois Association for Infant Mental Health (n.d.).

A Focus on DEI

For some time, the infant and early childhood field has voiced support for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Now professionals in this field are challenged to deepen their commitment to these values and take action to directly confront racial bias, White privilege, and power issues and to embrace social justice and antiracism.

This territory may feel dangerous for many professionals, filled with conflicting and sometimes troubling narratives fueled by strong emotions that run deep and have long histories in their cultures. It takes fortitude to address these issues.

Taking a too-careful stance toward talking about diversity is usually driven by the worry of offending others. But this reluctance interferes with our wishes to explore, question, and underscore our differences. Unless we invite the tension and confusion related to exploring the cultural context of our work in a deliberate manner, we will miss important opportunities to enrich our understanding about how our differences influence our work with children and families. (Heffron et al., 2007, p. 34)

The Reflective Interaction Observation Scale describes the content and characteristics of the interactions between the reflective supervision/ consultation participants. Photo: Shutterstock.com/fizkes

Developed and disseminated by the Tenets Initiative, the Diversity-Informed Tenets for Work With Infants, Children, and Families (Thomas et al., 2018, www.diversityinformedtenets.org) are “a set of guiding principles that could be used as a navigational tool to ensure that while immersed in their day-to-day work these professionals were steering toward a more equitable, inclusive, and socially just world for all infants, children, and families” (Thomas et al., 2019, Origin of The Tenets section, para. 1).

Whereas the goal of RS/C is to establish a collaborative partnership among participants, there are power differentials within these relationships.

Even with the best intentions, power dynamics and privilege differentials exist within these relationships, in part due to inherent distinctions in roles and scope of work. In addition, the professionals and influential leaders who determine the practice, research, policy, procedures, and funding opportunities that inform RS/C guidelines are typically members of the dominant culture, which can create power imbalances within the relationships. Notably, this is parallel to power differentials or invisible barriers experienced between administrators, supervisors, service providers, educators, and the families with whom they work. (Hause & LeMoine, 2022, p. 22)

RS/C supervisors and supervisees need to feel safe addressing power differentials—not only when the individuals involved come from the same or a similar racial or cultural background but especially when the supervisor is from the dominant culture and one or more supervisees are not. It is the responsibility of the supervisor to open conversations about power differentials (Stroud, 2010).

The infant and early childhood field has moved from referring to “cultural competence,” to “cultural sensitivity,” to “critical self-reflection and responsiveness.” The first two terms were other-focused, primarily shining the spotlight on other cultures, other individuals, and how others are “different” from those of the dominant culture. To better understand how those from the dominant culture can most effectively work across those differences, critical self-reflection is necessary to take stock of ourselves, our individual histories, our explicit and implicit biases, and our responses to current and historical events (Noroña, 2020). It requires a level of vulnerability, letting down our defenses to look at ourselves, to understand the thought processes and emotions that consciously or unconsciously inform our actions and interactions.

For some time, the infant and early childhood field has voiced support for diversity, equity, and inclusion. Photo: Shutterstock/Prostock-Studio

Critical self-reflection refers to the process of questioning one’s own assumptions, presuppositions, and meaning perspectives (Mezirow, 2006, as cited in Cheng et al., 2015; Noroña et al., 2021; Noroña & Raskin, 2020). It differs from other types of reflection because it involves identifying the assumptions ruling our actions, locating their historical and cultural roots, questioning their meaning (Stein, 2000), taking responsibility for their impact (e.g., through our words and actions) on others, and developing alternative ways of being and acting. Part of this process requires us to “challenge the prevailing social, political, cultural and professional ways of acting” (Stein, 2000, p. 1). Each individual’s capacity for critical self-reflection is plastic; it can change over time and in connection to shifting sociocultural, historical, and political contexts, and its evolution demands intentionality, time, space, and practice (Noroña, 2020; Thomas et al., 2019).

Responses (actions) must then emanate from this critical self-reflection. Throughout the RIOS guide, we have brought DEI issues to the forefront in the hope that through RS/C and the broader umbrella of reflective practice, we can increase our awareness, more effectively form authentic relationships, and actively address DEI issues.

Creating a Culture of Reflection

Just as RS/C principles are being applied to all aspects of a supervisor’s role in an organization, these principles are

changing practitioners’ work, transforming their interactions with peers at every level of the organization, in addition to their relationships with the families they serve. Programs that have invested in reflective practice for the long term have reported that they experience a work culture in which peer staff members are “reflective partners” for each other. Staff members have integrated the reflective stance and processes to the point that they do not always require the involvement of their reflective supervisor. Other programs have reported that staff members are able to contain their thoughts and feelings about evocative experiences, rather than reacting in the moment, because they know that they will have the opportunity to explore these experiences in a supportive environment during their regularly scheduled RS/C sessions (Watson & Neilsen Gatti, 2012; Watson, Storm, & Bailey, 2016). Likewise, program policies and procedures are being reexamined and infused with reflective content and processes.

During a RIOS framework training, the coordinator of an early childhood program reported that she had immediately applied the RIOS concepts by revamping her employee orientation process for a new hire. She changed the starting point of the orientation conversation from the agency’s goals and policies to asking the new staff member what she wanted to know about the agency to become an effective employee. The coordinator stated that this collaborative approach established a different connection between her and the new staff member and was a much more satisfying way to begin their supervisory relationship. (Christopher Watson, observation, 2018)

It’s clear that a reflective stance can have a profound impact on organizational culture as well as individual practice. It remains to be seen how our understanding of relationships, including those between supervisors and staff members, may further evolve over time.

The Active Ingredients of RS/C Sessions

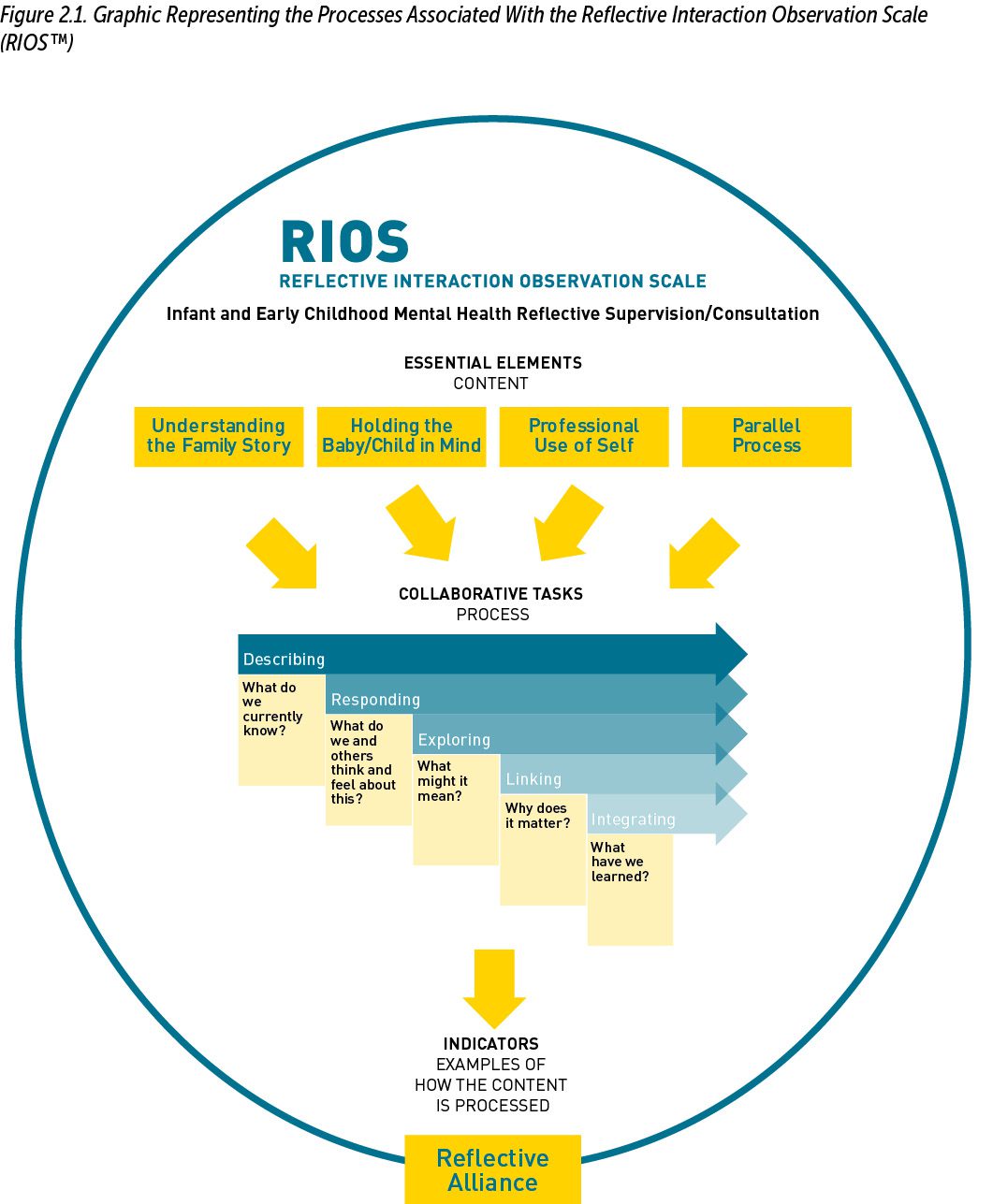

The RIOS framework identifies the “active ingredients” of an RS/C session that sets it apart from administrative supervision and other forms of relationship-based professional development such as traditional coaching, mentoring, and clinical supervision. These active ingredients are organized as five “Essential Elements,” the first of which is the RS/C relationship itself. Termed the Reflective Alliance, it describes the ways in which the supervisor and supervisee interact that are unique to RS/C in IECMH practice. The Reflective Alliance, a trusting and mutually respectful relationship between supervisor and supervisee, is the “vessel” that holds all the other component parts of RS/C. The four remaining Essential Elements focus on the content of the supervisory session. These elements are addressed through five distinctive reflective processes, referred to as Collaborative Tasks. The Collaborative Tasks are identified by using “Indicators” for each of the tasks. The Indicators are examples of the specific, concrete ways in which the dyad or reflective group pays attention to the content of the conversation (see Figure 2.1).

The RIOS was originally created to identify the components of RS/C so that they could be measured for research purposes. A separate manual and training procedure are available for those who want to use the RIOS as a research tool.4 The guide presents the RIOS as a framework to assist administrators, supervisors, and front-line staff in growing their knowledge and skills in the provision of RS/C. Programs have used it as the framework for relationships throughout their organization (e.g., Fitzgibbons et al., 2018). Some supervisors use the RIOS before a reflective session to remind themselves about the important content and reflective process components they might address. Others use it as a self-check following a session.

4 For more information, see Center for Early Education and Development (n.d; https://ceed.umn.edu).

The infant and early childhood field has moved from referring to “cultural competence,” to “cultural sensitivity,” to “critical self-reflection and responsiveness.” Photo: Shutterstock/Odua Images

Best Practice Guidelines for RS/C

The RIOS has been incorporated into the Best Practice Guidelines for Reflective Supervision/Consultation (BPGRS/C) published by the Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health (2018). The BPGRS/C “describe the knowledge, skills, and practices that are critical to reflective supervision/ consultation . . . to better ensure that those providing reflective supervision/consultation are appropriately trained and qualified” (Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health, 2018, para. 1, Items 2 and 3). These guidelines define the type of RS/C that is required to earn Endorsement for Culturally Sensitive, Relationship-Focused Practice Promoting Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health®. Those who are endorsed come from the full range of early childhood professional disciplines and have demonstrated completion of specialized education, work, in-service training, and RS/C experiences that lead to competency in the promotion and practice of IECMH.

The RIOS Guide and related materials are available at https://www.zerotothree.org/bookstore.

Author Bios

Christopher Watson, PhD, IMH-E®, is the founding director of the Reflective Practice Center in the Center for Early Education and Development (CEED) within the Institute of Child Development at the University of Minnesota. His current work is centered on reflective supervision/consultation to support practitioners working with infants and young children and their families. Dr. Watson and Martha Farrell Erickson, PhD, co-founded the interdisciplinary, post-baccalaureate Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Certificate Program at the University of Minnesota. Before returning to his home state of Minnesota, Dr. Watson was director of the California Education Innovation Institute, a statewide training program for educators and administrators based at California State University, Sacramento. In 2020, he received the Deborah J. Weatherston Infant Mental Health Leadership Award.

Maren Harris, MA, MFT, IMH-E®, is a retired family therapist and infant mental health mentor. She has extensive experience providing reflective supervision/consultation (RS/C) to individuals and groups working in the early childhood community, including with Early Head Start, Healthy Families America, and Nurse–Family Partnership. She has developed coursework in RS/C and has assisted in Reflective Interaction Observation Scale (RIOSTM) research at the Center for Early Education and Development at the University of Minnesota. Before her work as a reflective consultant, Maren worked for 10 years in a clinical setting with families adopting children who had experienced significant trauma.

Jill Hennes, MSW, LICSW, IMH-E®, has worked in home visiting and infant mental health as a home visitor, supervisor, consultant, and therapist. A licensed clinical social worker, she is endorsed in infant and early childhood mental health (clinical mentor) and holds a certificate in child abuse prevention studies from the University of Minnesota. At the Minnesota Department of Health, Jill learned about building a statewide system of support for public health home visiting programs, expanding infant mental health consultation and reflective practice. Jill is currently an independent consultant and trainer and continues to be intrigued and energized by the work of supporting the reflective practice and professional development of those who provide relationship-based services to families and their young children.

Mary Harrison, PhD, LICSW, IMH-E®, is an infant mental health specialist. She is a former research associate at the University of Minnesota Center for Early Education and Development, part of the Institute of Child Development. Her clinical practice experience includes work in infant and early childhood mental health in a variety of settings. She has published her research on reflective supervision/consultation (RS/C) and has been receiving and providing RS/C in different settings, including child protection and child care, for many years.

Alyssa Meuwissen, PhD, is a research associate in the Center for Early Education and Development at the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities, and she also is the research coordinator for their Center for Reflective Practice. Her work is focused on supporting positive interactions between young children and the adults who care for them and examining regulation through an infant and early childhood mental health perspective. She specializes in observational coding of dyadic interactions.

Suggested Citation

Watson, C., Harris, M., Hennes, J., Harrison, M., & Meuwissen, A. (2022). Essential elements of reflective supervision and consultation: The RIOS Framework. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 43(2), 26–31.

References

Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health. (2018). Best practice guidelines for reflective supervision/consultation. www.allianceaimh.org/reflective-supervisionconsultation

Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health. (2020, June). Reflective supervision/consultation requirements for endorsement®. www.allianceaimh.org/reflective-supervision-consultation

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss, Volume I: Attachment. Basic Books. (Original work published 1969)

California Association for Infant Mental Health. (n.d.). Specializing in infant–family and early childhood mental health. https://calaimh.org/professional-endorsement

Cheng, M., Pringle Barnes, G., Edwards, C., Valyrakis, M., & Corduneanu, R. (2015). Transition skills and strategies—Critical self-reflection. Enhancement Themes. www.enhancementthemes.ac.uk/docs/ethemes/student-transitions/key-transition-skills.pdf

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think. D. C. Heath and Company.

Fitzgibbons, S., Smith, M., & McCormick, A. (2018). Safe harbor: Use of the reflective supervisory relationship to navigate trauma, separation, loss, and inequity on behalf of babies and their families. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 39(1), 74–82.

Hause, N., & LeMoine, S. (2022). Beyond reflection: Advancing reflective supervision/consultation (RS/C) to the next level [Professional innovations discussion paper]. ZERO TO THREE.

Heffron, M. C., Grunstein, S., & Tilmon, S. (2007). Exploring diversity in supervision and practice. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 28(2), 34–38.

Heffron, M. C., & Murch, T. (2010). Reflective supervision and leadership in infant and early childhood programs. ZERO TO THREE.

Heller, S. S., & Gilkerson, L. (2009). A practical guide to reflective supervision. ZERO TO THREE.

Illinois Association for Infant Mental Health. (n.d.). Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Credential Project. www.ilaimh.org/what-we-do/infant-and-early-childhood-mental-health-credential-project-2

McCormick, A., Eidson, F., & Harrison, M. E. (2020). Reflective consultation with groups via virtual technology: What is best practice? ZERO TO THREE Journal, 40(3), 64–71.

Meuwissen, A. S., & Watson, C. (2021). Measuring reflection in reflective supervision/consultation sessions: Initial validation of the Reflective Interaction Observation Scale (RIOS). Infant Mental Health Journal. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21939

Noroña, C. R. (2020). A paradigm shift for group reflective supervision and consultation. [Unpublished manuscript].

Noroña, C. R., Lakatos, P. P., Wise-Kriplani, M., & Williams, M. E. (2021). Critical self-reflection and diversity-informed supervision/consultation: Deepening the DC:0–5 cultural formulation. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 42(2), 62–71.

Noroña, C. R., & Raskin, E. (2020). Cultivating radical healing [Handout]. Serving Immigrant Families Learning Collaborative, Cohort #1: Learning Session 1, Day 3: Caregiving for the Caregiver Part 2.

Rai, L. (2006). Owning (up to) reflective writing in social work education. Social Work Education, 25(8), 785–797. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470600915845

Schön, D. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. Jossey-Bass. Shirilla, J. J., & Weatherston, D. (Eds.). (2002). Case studies in infant mental health: Risk, resiliency, and relationships. ZERO TO THREE.

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Siegel, D. J., & Shahmoon-Shanok, R. (2010). Reflective communication: Cultivating mindsight through nurturing relationships. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 31(2), 6–14.

Smyth, J. (1989). Developing and sustaining critical reflection in teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 40(2), 2–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/002248718904000202

Sroufe, L. A. (1996). Emotional development: The organization of emotional life in the early years. Cambridge University Press.

Sroufe, L. A., Egeland, B., Carlson, E. A., & Collins, W. A. (2005). The development of the person: The Minnesota Study of Risk and Adaptation From Birth to Adulthood. Guilford Press.

Stein, D. (2000). Teaching critical reflection. ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult Career and Vocational Education, Center on Education and Training for Employment, College of Education, the Ohio State University.

Stinson, S., Tableman, B., & Weatherston, D. (2000). Guidelines for infant mental health practice. Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health.

Stroud, B. (2010). Honoring diversity through a deeper reflection: Increasing cultural understanding within the reflective supervision process. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 31(2), 46–50.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014, July).SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach (HHS Publication No. [SMA] 14-4884). https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

Thomas, K., Noroña, C. R., & St. John, M. S. (2019). Cross-sector allies together in the struggle for social justice: Diversity-informed tenets for work with infants, children, and families. ZERO TO THREE. www.zerotothree.org/resources/3392-cross-sector-allies-together-in-the-struggle-for-social-justice-diversity-informed-tenets-for-work-with-infants-children-and-families

Thomas, K., Noroña, C. R., St. John, M. S., & the Irving Harris Foundation Professional Development Network Tenets Working Group. (2018). Diversity-informed tenets for work with infants, children, and families. www.diversityinformedtenets.org

Watson, C., Harrison, M., Hennes, J., & Harris, M. (2016). Revealing “the space between”: Creating an observation scale to understand infant mental health reflective supervision. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 37(2), 12–19.

Watson, C., & Neilsen Gatti, S. (2012). Professional development through reflective consultation in early intervention. Infants and Young Children, 25(2), 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0b013e31824c0685

Watson, C., Storm, K., & Bailey, A. (2016). Building capacity in reflective practice: A tiered model of statewide support for local home visiting programs. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37, 640–652.