Karen Ruprecht, ICF Child Care State Capacity Building Center, Fairfax, Virginia

Angela Tomlin, Indiana University School of Medicine

Kelley J. Perkins, ICF Child Care State Capacity Building Center, Fairfax, Virginia

Stephan Viehweg, Indiana University School of Medicine

Abstract

Early care and education workers are increasingly recognizing their role in helping children who have experienced trauma, including extended parental separations due to incarceration. These children may have emotional reactions and behaviors that are particularly challenging in group settings. Moreover, early care and education professionals themselves have often had challenging experiences in their own lives. As a result, there is a need for training and support to help the workforce recognize the secondary trauma and stress associated with caring for these young children. This article will explore how to establish systems and policies that support the early care and education workforce who are on the frontlines of helping children cope with trauma.

Early care and education practitioners increasingly encounter families and young children who have a history of difficult life experiences (Osofsky, 2009; Yoches, Summers, Beeber, Jones Harden, & Malik, 2012). These experiences might include poverty, parental mental health challenges, living in unsafe housing or community environments, homelessness, child abuse and neglect, witnessing domestic or community violence, unpredictable and repeated separations due to parental incarceration, or foster care placement. Other traumatic events include serious accidents, fires, or natural disasters such as floods or hurricanes.

Recognition of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs; see Box 1) has drawn attention to the long-term impact of these events on children’s emotional and physical well-being (Felitti et al., 1998). Exposure to traumatic events in early childhood is linked with immediate risks such as delays in development (Burke, Hellman, Scott, Weems, & Carrion, 2011; Cprek, Williamson, McDaniel, Brase, & Williams, 2020). In addition, ACEs can contribute to long-term mental and physical health problems including increased risk for cancer, diabetes, and early death (Felitti et al., 1998). The research on ACEs indicates these experiences are not uncommon, nor do they occur alone (Turney, 2018). According to national data, 10.9% of children younger than 6 years old have experienced two or more ACEs (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, 2017).

- Physical abuse

- Sexual abuse

- Verbal abuse

- Physical neglect

- Emotional neglect

- A family member who is depressed or diagnosed with mental illness

- A family member addicted to alcohol or another substance

- A family member in prison

- Witnessing a mother being abused

- Losing a parent to separation, divorce, or other reason.

Other ACE surveys have included additional ACEs such as exposure to racism, gender discrimination, witnessing a sibling being abused, witnessing violence outside the home, witnessing a father being abused by a mother, being bullied by a peer or adult, involvement with the foster care system, living in a war zone, living in an unsafe neighborhood, or losing a family member to deportation. Source: ACES Too High

The recognition of ACEs in young children has not only increased awareness of how trauma impacts young children, but it has also reinforced the need to develop the skills and competencies of the early childhood workforce who may encounter children and families experiencing trauma. Children exposed to trauma need adults who can provide environments that are consistent and help them feel safe (Holmes, Levy, Smith, Pinne, & Neese, 2015). Professional development resources and training offered by state and national organizations regularly address topics such as behavior management, social–emotional development, recognizing trauma in young children, and how to create environments for children who are exposed to trauma. Often, these trainings are focused on helping children cope or develop skills to help them manage their complex emotions. Some trainings also focus on what the early childhood professional can do to help mitigate the traumatic experiences through specific teaching practices, room arrangements, or teaching calming techniques.

States have also recognized the impact that childhood trauma plays in children’s lives and have designed core knowledge and competencies to reflect the importance of understanding trauma and its impact on children. Professional credentials for those working with young children, including the Endorsements offered through the Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health (n.d.), include documentation of competence in trauma-informed practice. Organizations such as ZERO TO THREE, the National Association for the Education of Young Children, and others have produced position statements, webinars, or resources that help caregivers support and recognize the impact trauma has on young children (National Association for the Education of Young Children , n.d.; ZERO TO THREE, n.d.). These resources provide important information for parents and professionals on how to work with young children to help them cope through these difficult life circumstances. However, there is much less information available to help early care and education professionals cope with their own trauma. This article will focus on secondary trauma in early care and education fields, highlight the voices of early childhood professionals who work with children and families who have experienced incarceration and other difficult life circumstances, and suggest how systems and policies can help support the workforce. Finally, we offer a trauma-informed leadership perspective for early childhood organizations using an implementation science framework.

Secondary Trauma and the Impact on the Early Childhood Workforce

Professionals who support young children and families who experience trauma may experience secondary trauma, reacting in ways that challenge their well-being, health, and effectiveness. Secondary trauma—sometimes referred to as compassion fatigue or vicarious trauma—is defined as “the emotional duress that results when an individual hears about the firsthand trauma experiences of another” (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2011). As a result of secondary trauma, early childhood professionals can experience secondary traumatic stress, which is a progressive and cumulative process caused by prolonged and intense contact with families and children exposed to stress (Coetzee & Klopper, 2010).

Secondary traumatic stress can have the same effect on an early childhood professional as posttraumatic stress disorder, which can cause people to withdraw, feel angry and irritable, and have difficulties sleeping, among other symptoms (Perry, 2014). In addition, working daily with young children and families who face adversity can also trigger stress-related behaviors in adults, making it difficult for them to provide sensitive and responsive caregiving to the children they serve. While the effect of working with people who have experienced trauma such as police officers, firefighters, or emergency medical professionals is well documented, less well known are the effects that working closely with such families may have on early childhood professionals, including home visitors, teachers, and other child care professionals (Figley, 2012; Perry, 2014; West, Berlin, & Jones Harden, 2018).

Research from related fields exploring why people in helping professions such as the early care and education field may be prone to secondary trauma is limited and mixed. Some research has shown that social service providers tend to have a higher number of ACEs than the general population, which can contribute to susceptibility to secondary trauma (Esaki & Larkin, 2013), while other researchers have found no relationship between ACEs and secondary traumatic stress (Hiles Howard et al., 2015). Other research has found that child welfare workers and home visitors who have repeated and frequent exposure to families and children experiencing trauma may exhibit signs of secondary trauma symptoms. Some research has suggested that female social workers and social workers with higher levels of empathy and lower levels of perceived support have been found to have higher levels of secondary trauma (Choi, 2011; MacRitchie & Leibowitz, 2010).

There have been few studies on secondary traumatic stress in the early care and education field. Some studies have focused on workforce well-being and depression among early childhood professionals (Roberts, Gallagher, Daro, Iruka, & Sarver, 2019) and psychological well-being (Madill, Halle, Gebhart, & Shuey, 2018). These studies suggest that supportive workforce and organizational climates can benefit early childhood professionals and should be considered in quality efforts and as workforce supports. In a study of Early Head Start home visitors, researchers found that home visitors experienced varying degrees of secondary traumatic stress. Those that experienced secondary traumatic stress were more likely to have fewer years of experience (less than 5 years), reported more depressive symptoms, had greater empathetic personal distress, and had perceptions of higher job demands (West et al., 2018).

Perry (2014) provided additional reasons why early childhood professionals may be prone to secondary stress. First, early childhood professionals tend to empathize with the children and families they serve. Empathy allows the early childhood professional to understand a child’s feelings and can help deepen the relationship, so the child knows their teacher is there for them when they need help or reassurance. However, empathizing to a point where the early childhood professional is consistently worried or overly anxious about a child or family may be unhealthy. Second, early childhood professionals may have some unresolved trauma in their own lives, and listening to similar trauma experiences with children and families in their care may trigger memories of their own experiences. Third, early childhood professionals who feel isolated, undervalued, and disrespected may not have the capacity to tolerate traumatic stress. When systems are fragmented and disjointed (e.g., when a child experiences something traumatic and the various professionals don’t work together to develop a team-oriented approach to working with the child) early childhood professionals can feel more stress. Finally, a lack of resources within the system, such as training, reflective supervision, and leadership supports, can exacerbate secondary traumatic stress.

Parental Incarceration and Young Children

Young children living with a parent who has experienced incarceration is becoming increasingly common. National surveys estimate that 3.9% of children under 6 years old live with a parent who has been incarcerated (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, 2017). Multiple ACEs are likely for children with a parent who experienced incarceration. These children are exposed to nearly 5 times as many other ACEs as their peers who are not exposed to parental incarceration (Turney, 2018). Thus, children of incarcerated parents are a specific population that must be considered when planning for training for the early childhood workforce.

Young children are not the only ones impacted by incarceration. Data suggest that nearly 1 in 2 adults (45%) has had an immediate family member (parents, brothers, sisters, children, or current partner) spend at least one night in jail or prison (Fwd.US, 2018). Thus, many early childhood professional staff members may have direct experience with incarceration as well. It is important for early childhood leaders to recognize and effectively support staff members who may have experienced trauma in their own lives or may experience symptoms of trauma when working with young children and families facing adversity. The following section describes the results of a study focused on early childhood education (ECE) providers and their needs in working with children of incarcerated parents.

ECE Professional Needs

A mixed methods study on what ECE professionals need to work with children of incarcerated parents highlighted an urgent need for specific supports for the field (Ruprecht, Tomlin, & Spector, 2019). During a 6-week period in 2017, researchers sent an electronic survey to 3,242 known child care directors or owners who served prekindergarten-age children in a midwestern state. A total of 667 surveys were returned, representing a 21% return rate. The purpose of the survey was to determine the number of children from 3–5 years old in formal child care arrangements (i.e., licensed or regulated child care) who had a family member that was incarcerated.

Results from the survey indicated 51% of child care providers (n = 338) had at least one child from 3–5 years old in their care who had an incarcerated parent, representing 1,397 children. Results also indicated that 41% identified as family child care providers, followed by 26% faith-based institutions, 21% licensed centers, 7% as school-based programs, and 5% as other. There was variation in participation in the state’s quality rating and improvement system, with 27% indicating they were not enrolled in the state’s voluntary system, 20% were at the first level, 8% at the second level, 28% as the third level, and 17% at the highest, or fourth level.

Empathy allows the early childhood professional to understand a child’s feelings and can help deepen the relationship.

As part of the online survey, researchers asked providers if they were interested in participating in voluntary focus groups to better understand their experiences when working with children and families facing incarceration. Researchers conducted six focus groups with 25 child care providers. Providers represented family child care owners and directors of licensed child care centers, school-based preschools, Head Start, and faith-based child care programs. Researchers asked providers what they and their staff members needed to better support families experiencing incarceration. While most providers acknowledged that training was helpful, they noted that training is not sufficient in meeting their needs.

And it seems like a lot of trainings we go to, it’s all upbeat. Everything is all unicorns. If you’re doing it this way all the time, you won’t have an issue. I don’t know what kind of world they’re living in. And I applaud their effort in trying to do training and the thought process behind it. But what works in academia doesn’t necessarily work in the classroom.

The training talked about children’s trauma and the trainer gave an example of a thunderstorm. I know that can be traumatic for some kids, but come on, I’m working with kids in my classroom who’ve been sexually abused. We need real examples and real situations of children in trauma.

These comments echoed results from a previous study in which an Early Head Start home visitor expressed a need for more realistic training that highlights real families in real situations and not “the perfect family” (West et al., 2018).

Although training can be helpful, there was consensus that training was not enough to help the providers understand how to work with the children in their care. Focus group participants often spoke of needing specific supports that reached beyond training and wanting someone in the room to help them understand the child’s behavior and to guide them to an appropriate response.

I want to know when you are sitting on the floor and this is the 10th time that this child has a meltdown, and you’ve exerted every option, what do you do next? In that moment, right then and there what are you doing to help me, so that I can help them?

One Head Start provider shared that while the training and resources are directed at helping children and improving teaching practices in the classroom, the staff also needs support.

I think a lot of times we think about a mental health specialist, and we place all of the responsibility on that mental health specialist, or that Head Start teacher. We had that. They were there for the children. Only the children. And if anything were to be sparked out of this opportunity, I would definitely want to advocate that mental health specialist not be funded just for children, but to ensure the support and resources, and almost just a listening person. A shoulder to cry on, on occasion, for our caregivers and teachers.

Systems and Policies That Support the Workforce

As evidenced by the research and focus groups, ECE professionals need support to help process their own complex emotions in working with families that face adversity. In order to effectively address the needs of the workforce, systems and policies need to be in place to help providers recognize secondary traumatic stress, help staff members engage in self-care, provide resources to staff members who need additional help, and develop ways to incorporate a leadership and organizational framework to support the staff as they work with children and families facing adversity. The following framework for staff support was adapted from Massachusetts “flexible framework” for trauma-sensitive practices and supports for K-12 schools (McInerney & McKlindon, n.d.; Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative, n.d.).

Develop a Trauma-Informed Culture and Infrastructure/Leadership

ECE administrators and leaders can develop a culture and climate to support the workforce through:

- Recognizing the impact and signs of secondary trauma and reviewing agency policies to ensure they reflect an understanding of the role of trauma in staff members. The leadership staff should be well-versed and knowledgeable about secondary trauma. There are a number of online resources available through the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (n.d.) and the Administration for Children and Families resource guide on secondary traumatic stress (n.d.) that can help the leadership staff understand and recognize secondary trauma.

- Engaging in thoughtful strategic planning. Involve staff members in developing the agency’s strategic plan to ensure staff member voices are represented in the understanding of trauma and of the needs of the frontline staff who are working with children who experience trauma. Ensure that an understanding of the impact of working with families and children facing adversity is part of the strategic plan.

- Encouraging staff members to take care of their mental health as much as their physical health. Review agency policies to determine whether the importance of mental health and self-care for the staff is equated with physical health needs. Some agencies may be able to offer programs on staff wellness and self-care at the workplace or with a community-based program. Agencies can also weigh the number of paid time off days to the staff to account for secondary stress, particularly if staff members work with a number of children and families experiencing trauma. For example, agencies may want to examine whether staff members are allowed to take paid leave without producing documentation from a medical provider.

- Developing community partnerships. Agencies should review their community partnerships to ensure there are an adequate number of partnerships with organizations that can provide support and resources for the staff as well as for children and families. For example, an agency may want to partner with the local child welfare agency on specific training needs identified by the staff.

- Developing ways for staff members to talk and engage with each other within and outside of work. Promote and encourage a positive staff climate by providing space where they can decompress during the day, such as a comfortable staff lounge. Leaders can also recognize positive attributes in staff members by sending or posting notes of appreciation or recognition of the staff. Encourage staff members to build relationships with each other outside of the workplace by providing opportunities for social activities and team-building activities. When staff members feel connected and supported by their workplace, they may develop more coping strategies to address secondary traumatic stress.

Encourage staff members to build relationships with each other outside of the workplace by providing opportunities for social activities and team building activities.

Provide Staff Training and Professional Development

Incorporate agency-wide and individual training on how trauma affects the workforce through:

- Developing individual professional development plans with the staff. Most staff training needs focus on required trainings for licensing or certification. Consider working with staff members at the time of hire or throughout the year to develop a professional development plan that includes a discussion on self-care strategies, work-life balance, time management, and ways to address stress. Doing so can help keep the discussion open regarding individual staff needs.

- Assessing staff training needs and staff practices on an ongoing basis. Talk with staff members about what training would help them in their response to working with children and families experiencing trauma, and identify outside supports needed to help staff members receive those trainings. Ensure that these staff training needs are represented in the agency’s strategic plan and that the training focuses on the workforce needs as well as on strategies to help the staff improve their practices in working with children and families. Observe staff members in action to assess their practices and whether secondary traumatic stress has an impact on them.

- Offering opportunities for the staff to engage in reflective practice and supervision. Reflective practice in early childhood is described as the ability to use reflective activities and reflective processes while actively engaged in work with young children and families (Brandt, 2014). Ideally, staff members would be able to slow down and think carefully in the moment in order to better understand what is happening in a given situation with a child and family. This level of skill is developed over time, with thoughtful effort and experience, and requires self-awareness. Gaining this level of skill requires the use of reflective activities and can include working with a trusted mentor within a reflective supervision or consultation relationship (Heffron & Murch, 2010) or individual reflective activities, such as journaling or other reflective writing (Brandt, 2014). Reflection promotes a focus on the present so that it is more possible for staff members to be truly aware of their own experiences, their responses to those experiences, and their responses to the experiences of other people. Taking time to reflect is thought to increase the quality of the work, leading to better decision making, increased confidence or feelings of effectiveness, and enhanced ability to take in and use new information (Tomlin & Viehweg, 2016). Reflection may be most helpful when situations are most complex, including those that involved interactions with traumatized children and families. During these highly charged moments, use of reflective skills can help early childhood professionals manage their own competing emotional and cognitive processes, take in and make sense of the complex family situations, and better tolerate the uncertainty inherent in these situations (Weston, 2005).

Reflection may be most helpful when situations are most complex, including those that involved interactions with traumatized children and families.

Offer Access to Resources and Services

Some staff members may need additional resources and services to help them cope with and process their feelings and emotions.

- Provide access to mental health consultation for the staff. Mental health consultation can help staff members understand their responses and provide them with the support they need to address the impacts of secondary traumatic stress. A mental health consultant can provide an opportunity for staff members to confidentially discuss specific instances with children and families to help them recognize and reflect on their experiences of secondary trauma and can help them develop coping strategies.

- Work with other ECE leaders and community organizations to support the staff. While a mental health consultant may not be in the budget, it is important to seek resources to provide this resource for the staff. Think creatively and reach out to local child welfare organizations, child care resource and referral agencies, local universities, local funders such as the United Way, or other entities to help develop a plan to secure this resource for staff members. For example, if several ECE agencies need a mental health consultant, there might be opportunities to co-fund a position. Local universities may have graduate training programs in counseling, therapy, or related fields that have students who need practicum experiences. Child care providers may want to reach out to their local school districts and suggest a partnership.

Implementing a Systems Approach to Addressing Trauma in the Workforce

For many ECE leaders, implementing policies and procedures to support the workforce will be a new endeavor. Implementation of any new workforce initiative is complex and multifaceted. To address these difficulties, leaders must approach the stages of implementation for an initiative in an intentional manner. Implementation science offers many resources to consider as they begin a new initiative (Metz, Naoom, Halle, & Bartley, 2015).

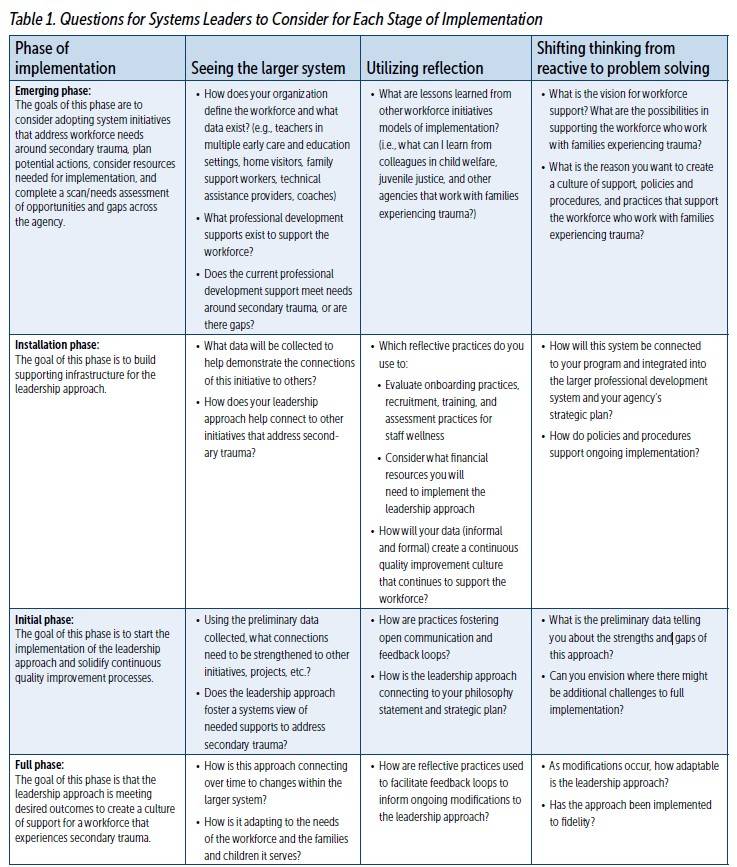

Prior to implementing a new system focused on addressing secondary trauma, leaders should think about how it will integrate into the overall organizational structure. For example, implementing an organizational leadership approach that develops a culture focused on supporting the workforce who experience secondary trauma will require more than certain knowledge, supports, and resources of the leadership staff. It will require a systems approach with leaders who possess the following core capabilities of systems leaders (Senge, Hamilton, & Kania, 2015): (1) seeing and helping others see the larger system; (2) using reflection and enabling deep shared reflection and; (3) shifting thinking from being reactive to problem solving. Table 1 applies these core capabilities to the stages of implementation science (Emerging, Installation, Initial, and Full) within the context of workforce initiatives and shares questions for leaders to consider.

Conclusion

ECE practitioners are often on the frontline of helping children cope with trauma. When traumatic events happen in children’s lives, ECE professionals need the same level of support and resources to help them recognize the emotional and physical toll it can take to work day in and day out with young children who have experienced trauma.

Recognizing and addressing the effects of secondary trauma are necessary for early childhood professionals to avoid becoming overwhelmed and to have the skills to respond effectively to the needs of children and families. ECE leaders should integrate a systems approach to implementing new programs of support for the workforce. Program leaders should also incorporate self-care and reflection methods into professional development activities for the early childhood workforce and ensure that organizational supports and processes are in place that continue to elevate the importance of caring for the workforce.

Learn More

Following are some resources to help early care and education leaders think about implementing these systems and policies.

- The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NTSN) has resources to help early care and education professionals learn about secondary traumatic stress. Among its resources is a set of core competencies and a self-rating scale for professionals who provide trauma-informed supervision to rate where they feel comfortable in their skill set, where they may need more training, or if a competency is not yet in their skill set.

- Support for Teachers Affected by Trauma is a series of five free online modules that describe secondary traumatic stress, risk factors for teachers, the impact it can have, and self-care skills. Although created for preschool-12th grade teachers, the information in the modules is applicable for professionals who work with young children. Trainers or technical assistance providers may want to view the modules in advance to help understand the content in each module and to use it as a way to begin a conversation with staff members about secondary traumatic stress.

- Teaching Tolerance offers a free toolkit for early care and education professionals to learn self-care strategies.

- The Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) measure can help professionals assess and learn how compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress may impact them. The website offers sample presentation slides, tools, and handouts for trainers to use, as well as information on how to administer and score the

Authors

Karen Ruprecht, MPA, PhD, has worked in the field of early care and education at the local, state, and national levels. Her research and professional interests are focused on the intersection of research, policy, and practice. In her current role, Dr. Ruprecht manages a team that provides intensive technical assistance to state child care administrators and their staff to enhance their leadership skills and to help them meet Child Care Development Fund requirements. Her previous research and evaluation work focused on studying continuity of care for infants and toddlers; conducting Quality Rating Improvement System validation, implementation, and longitudinal studies; and evaluating a state-funded pre-k initiative. She has worked directly with state child care administrators and their teams to develop, design, and disseminate research. Dr. Ruprecht is an alumna of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Interdisciplinary Research Leader Fellow program where she researched the impact of parental incarceration on young children, families, and child care providers.

Angela Tomlin, PhD, IMH-E®, is a clinical psychologist and professor at the Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM). At IUSM, she directs the section of Child Development and Riley Child Development Center, Indiana’s LEND interdisciplinary training program. Dr. Tomlin provides clinical services to families with children with neurodevelopmental disabilities, supervises graduate trainees, provides reflective consultation in the community, and is a frequent presenter on topics including autism, behavior management, and infant mental health. She is the author or co-author of 20 publications and with Stephan Viehweg authored Tackling the Tough Stuff: A Home Visitor’s Guide to Supporting Families at Risk in 2016. With team members, Dr. Tomlin was selected to participate in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Interdisciplinary Research Leader Program, with a research focus on supporting children of incarcerated parents.

Kelley J. Perkins, PhD, currently serves as the managing director of the Infant/Toddler Specialist in the State Capacity Building Center. She is also the co-director of the Early Childhood Leadership Institute at Rowan University in New Jersey. She brings more than 20 years of experience in the field as a teacher, technical assistant, and faculty member. Dr. Perkins’ research and evaluation efforts focus on professional development and early childhood policy in support of quality, supply, and access to services for young children and their families.

Stephan Viehweg, LCSW, ACSW, IMH-E®,CYC-P, is the associate director of the Riley Child Development Center, Indiana LEND at the Indiana University School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, and the associate director of the Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis Center for Translating Research Into Practice. He currently serves as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Learn the Signs. Act Early Ambassador to Indiana. He is founding chair of Infancy Onward (Indiana’s association for infant mental health), founding president of Family Voices Indiana, treasurer of Mental Health America of Indiana, and serves a governor appointment to the Indiana Behavioral Health Professions Licensing Board. He is co-author of Tackling the Tough Stuff: A Home Visitor’s Guide to Supporting Families at Risk.

Suggested Citation

Ruprecht, K., Tomlin, A., Perkins, K. J., & Viehweg, S. (2020). Understanding secondary trauma and stress in the early childhood workforce. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 40(4), 41–50.

References

Administration for Children and Families. (n.d.). Resource guide to trauma-informed human services. Retrieved from source link.

Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health. (n.d.). Licensing. Retrieved from source link.

Brandt, K. (2014). Transforming clinical practice through reflection work. In K. Brandt, B. Perry, S. Seligman, & E. Tronick (Eds.), Infant and early childhood mental health: Core concepts and clinical practice (pp. 293–307). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Burke, N., Hellman, J., Scott, B., Weems, C., & Carrion, V. (2011). The impact of adverse childhood experiences on an urban pediatric population. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35, 408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.02.006.

Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. (2017). 2017–2018 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) data query. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health supported by Cooperative Agreement U59MC27866 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau (HRSA MCHB). Source link CAHMI

Choi, G. (2011). Organizational impacts on the secondary traumatic stress of social workers assisting family violence or sexual assault survivors. Administration in Social Work, 35, 225–242.

Coetzee, S. K., & Klopper, H. C. (2010). Compassion fatigue within nursing practice: A concept analysis. Nursing & Health Sciences, 12(2), 235–243.

Cprek, S. E., Williamson, L. H., & McDaniel, H., Brase, R., & Williams, C. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences (ACES) and risk of childhood delays in children ages 1–5. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 37(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-019-00622-x

Esaki, N., & Larkin, H. (2013). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among child service providers. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 94(1), 31–37.

Felitti V. J., Anda R. F., Nordenberg D., Williamson D. F., Spitz A. M., Edwards V., Koss M. P, & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 14, 245–258.

Figley, C. R. (2012). Helping that hurts: Child welfare secondary traumatic stress reactions. CW360: Secondary Trauma and the Child Welfare Workforce, 4–5. Source link

Fwd.US. (2018). Every second: The impact of the incarceration crisis on America’s families. Source link

Heffron, M. C., & Murch, T. (2010). Reflective supervision and leadership in infant and early childhood programs. Washington, DC: ZERO TO THREE.

Hiles Howard, A., Parris, S., Hall, J., Call, C., Becker Razuri, E., Purvis, K.,& Cross, D. (2015). An examination of the relationships between professional quality of life, adverse childhood experiences, resilience, and work environment in a sample of human service providers. Children and Youth Services Review, 57, 141–148.

Holmes, C., Levy, M., Smith, A., Pinne, S., & Neese, P. (2015). A model for creating a supportive trauma-informed culture for children in preschool settings. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(6), 1650–1659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9968-6

MacRitchie, V., & Leibowitz, S. (2010). Secondary trauma stress, level of exposure, empathy, and social support in trauma workers. South African Journal of Psychology, 40(2), 149–158.

Madill, R., Halle, T., Gebhart, T., & Shuey, E. (2018). Supporting the psychological wellbeing of the early care and education workforce: Findings from the National Survey of Early Care and Education. OPRE Report #2018-49. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

McInerney, M., & McKlindon, A. (n.d.). Unlocking the door to learning: Trauma-informed classrooms & transformational schools. Education Law Center

Metz, A., Naoom, S. F., Halle, T., & Bartley, L. (2015). An integrated stage-based framework for implementation of early childhood programs and systems (OPRE Research Brief OPRE 2015-48). Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (n.d.). Coping with stress and violence. Source link

National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (n.d.) Secondary trauma stress. Source link

National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2011). Secondary traumatic stress: A fact sheet for child-serving professionals. Source link

National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team. (2013). Number and characteristics of early care and education (ECE) teachers and caregivers: Initial findings from the National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE). OPRE Report #2013-38, Washington DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Osofsky, J. D. (2009). Perspectives on helping traumatized infants, young children, and their families. Infant Mental Health Journal, 30(6), 673–677.

Perry, B. D. (2014). The cost of caring: Secondary traumatic stress and the impact of working with high risk children and families. Source link

Roberts, A., Gallagher, K., Daro, A., Iruka, I., & Sarver, S. (2019). Workforce wellbeing: Personal and workplace contributions to early educators’ depression across settings. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 61, 4–12. Source link

Ruprecht, K., Tomlin, A., & Spector, S. (2019). Child care providers experiences with children of incarcerated parents. [Unpublished raw data].

Senge, P., Hamilton, H., & Kania, J. (2015). The dawn of system leadership. Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter, 27–33.

Tomlin, A. M., & Viehweg, S. A. (2016). Tackling the tough stuff: A home visitor’s guide to supporting families at risk. Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative. (n.d.). The Flexible Framework: Six elements of school operations involved in creating a trauma sensitive school. Source link

Turney, K. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences among children of incarcerated parents. Children and Youth Services Review, 89, 218–225. Source link

Weatherston, D. J. (2000). The infant mental health specialist. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 21(2), 3–10.

West, A., Berlin, L., & Jones Harden, B. (2018). Occupational stress and wellbeing among Early Head Start home visitors: A mixed methods study. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 44, 288–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.11.003

Weston, D. (2005). Training in infant mental health: Educating the reflective practitioner. Infants and Young Children, 18(4), 337–348.

Yoches, M., Summers, S. J., Beeber, L. S., Jones Harden, B., & Malik, N. M. (2012). Exposure to direct and indirect trauma. In S. J. Summers & R. Chazan-Cohen (Eds.), Understanding early childhood mental health: A practical guide for professionals (pp. 79–98). Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

ZERO TO THREE. (n.d.). Trauma and stress. Source link.