Deborah Roderick Stark, Harwood, Maryland

Abstract

Early home visiting programs have provided a lifeline of support to American Indian and Alaska Native families hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. This article is about how three Tribal Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (Tribal MIECHV) grantees have approached the pandemic with agility, adaptability, and innovation. Home visitors are responding to the needs of families, supporting one another, and shining a light of hope.

The COVID-19 pandemic is having an outsized impact on the American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) community. For some, the pandemic may be triggering trauma that AIAN people have endured since colonization. For all, the rapid spread of the virus, especially on reservations, is threatening the lives of too many loved ones.

Even during the darkest moments of the pandemic, home visiting programs have been able to sustain a light of hope for families. When other providers paused or ended services, home visitors continued to show up for families.

Editor’s Note :This publication is an abbreviated version of an issue brief produced by Programmatic Assistance for Tribal Home Visiting (PATH) for the Administration for Children and Families under contract #HHSP233201500130I – HHSP23337001T

Disproportional Impact for AIAN Families

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention noted that the AIAN community has experienced disproportionate rates of infection and mortality during the pandemic. Compared to White non-Hispanic persons, AIAN infection rates are 1.8 times higher and mortality rates are 2.6 times higher (Trust for America’s Health et al., 2020). Since those data were collected, COVID-19 has only worsened. Tribal communities implemented lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, curfews, and closures of reservation borders to stop the spread of the virus.

The pandemic is taking a toll on Tribal Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (Tribal MIECHV) families, including the following:

- Emotional challenges: Home visitors report that families are experiencing more stress, anxiety, and depression. Social isolation is a concern, and many cultural and community supports families normally turn to are not available. Grantees note a reduction in the success rate of breastfeeding, increases in intimate partner violence, and substance misuse relapse. Pregnant women nearing delivery worry that birthing support people will not be allowed in the hospital or clinic.

- Financial challenges: Grantees report significantly more underemployment and unemployment among families. Food insecurity is unprecedented. Housing challenges are magnified. Many families lack basic supplies like diapers.

- Connections to needed services: Broadband issues are a challenge, making it either difficult or impossible to participate in virtual home visits. Many families don’t have access to early childhood education or Head Start, or they worry it is not safe. Parents are overwhelmed guiding children through remote learning. Some are putting off well-child visits, immunizations, and dental checks.

Families are not alone in their struggle. The pandemic is having a toll on home visitors and program leaders as well.

The kids and I tested positive. I was sick for just 4 or 5 days, but the brain fogginess lingered. I also lost my grandpa to COVID. It took him in 24 hours. It’s truly one heartache after another and I am trying to continue moving forward and doing the best I can for everyone. —April Winters, home visitor, Taos Pueblo

COVID is a marathon and it is affecting all of us—staff and families. Fortunately, Cook Inlet Tribal Council, Inc. (CITC) recognizes that we are not just staff, we are community members and parents trying to homeschool. —Deborah Northburg, senior director, Child and Family Services Department, CITC.

Despite the enormity of the challenges, Tribal MIECHV programs are persevering. Program leaders knew home visiting supports were needed more than ever during the pandemic. With that understanding, they approached the pandemic with creativity and innovation, all in service of the families and communities they serve.

From the Field

The three grantees interviewed were able to sustain a light of hope for families. CITC benefited from long-term leadership and a strong multiservice organizational structure, connection to values, and the adoption of practices to support staff well-being. Taos Pueblo benefited from a small but mighty team that valued communication and co-creation no matter the challenge, a nimble approach to delivering services, adapting resources from others, and their connection to nature. The home visiting program at Riverside-San Bernardino County Indian Health Clinic, Inc. (RSBCIHCI) benefited from being connected to a large health care company, commitment to supporting staff, and a strong sense of community responsibility.

CITC

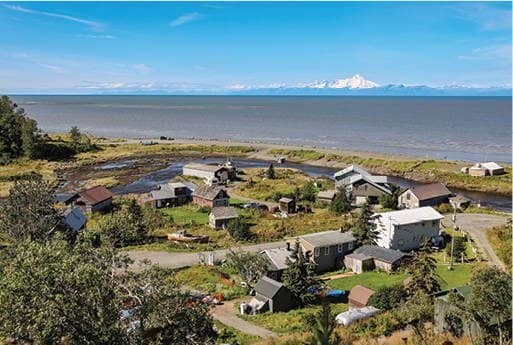

CITC, a grantee since 2016, provides the Parents as Teachers (PAT) home visiting model to families with children birth to kindergarten living in Anchorage, Alaska. The home visiting program, known as Ch’anik’en (“Little One” or “Child”), is nested within the CITC multiservice system and can serve up to 60 families.

In anticipation of the pandemic, there was a session of the Board of Directors in March 2020 to develop an emergency operations policy. Northburg said,

We got quickly to work to develop structure around what telework would look like. We created tips and guidelines for staff and managers, got Zoom subscriptions and trained staff on how to use it. Effective and regular communication was key–from the CEO, across departments, and within the home visiting program.

Three things stand out as important to CITC’s ability to navigate the pandemic: (1) the long-term leadership, organizational structure, and multiservice nature of the company, (2) connection to a clear set of cultural values, and (3) a deep concern and support for staff wellness.

Long-Term Leadership, a Strong Organizational Structure, and Multiservice Support

CITC benefits from having a visionary leader at the helm. President and CEO Gloria O’Neill has been in this role for more than 20 years. During her time, the organization has expanded to serve more than 12,000 people each year across multiple programs. Service areas focus on nurturing families, growing graduates, finding jobs, and achieving sobriety. In 2006, all of the programs were co-located, which allows staff to work closely together, including engaging in rapid problem solving.

CITC’s organizational structure supports bi-directional sharing of experiences from leadership, staff, and participants. The structure includes the following:

- CITC Leadership Council. The Leadership Council is made up of directors and senior directors of the various programs, plus the directors of planning, accounting, finance, communication, strategic projects, and other support services.

- President’s Council. The President’s Council is made up of the president and CEO, the executive vice president and chief financial officer, and chiefs of operations, technology, legal, and administration.

- Board of Directors. The 17-person Board of Directors is comprised of a representative from each of the eight federally recognized tribes within the Cook Inlet region, as well as nine representatives from Cook Inlet Region, Inc., which is a land-based Alaska Native regional corporation with more than 9,000 shareholders.

Broadband issues are a challenge, making it either difficult or impossible to participate in virtual home visits. Photo: Native Health, Inc.

According to Northburg,

The magic of this is that you have different perspectives from the broader systems administration of the President’s Council to the direct impact on staff and participants from the Leadership Council. This ensures we contemplate all of the aspects and consequences of policy changes together.

Leading With Values

Twenty-five years ago, CITC participants, staff, and community thought leaders adopted a set of values as part of a sustainability plan. The values provided a “north star” for the work and were incorporated into many aspects of the program from service delivery, to communication inside and outside the organization, to hiring and staff evaluations. Some staff suggest that the values contribute to their inner strength, their freedom to dream big, and their ability to persevere in times of challenge.

Investing in Staff Well-Being

A Board-approved definition of Spiritual Wellness sets the tone for the care and attention of staff.

Spiritual Wellness is inner Balance, Belonging, Faith, Grace, Kindness, Love and Peace. It is nurtured through Relationships with self, others, and a power greater than ourself. Spiritual Wellness is discovered through connections to each other, traditions, land and our humanness: mind, body, and spirit. (personal communication, G. O’Neill, April 9, 2020)

In a communication to staff during the early days of the pandemic, O’Neill wrote about the importance of wellness: “This is a gift we can give ourselves—the grace of spending time on our own wellness…We cannot be present and supportive for others without first taking care of ourselves” (personal communication, April 9, 2020). O’Neill and the Board implemented two policies that stand out as exemplars:

- Wellness stipends. Staff were offered a one-time $50 wellness stipend at the beginning of the pandemic. Some used the stipend to subscribe to meditation apps; others purchased audiobooks and journals; still others used it for virtual exercise classes. More recently, recognizing staff wellness as an ongoing priority, CITC implemented a $25 monthly stipend for all staff.

- Wellness and self-care time. Staff are allowed 30 minutes per day during work hours for wellness or self-care activities. This might include taking a walk, meditating, listening to music, journaling, breathing exercises, or other centering activities. Home visiting staff are also encouraged to participate in virtual mindfulness sessions organized by the Administration for Children and Families Tribal Home Visiting Program.

In addition to the wellness stipend and personal time, a licensed professional conducts group talking circles. One-on-one sessions are available, too, if staff need additional support. Recognizing that many of the staff have children at home, CITC has designated a space where children can gather to work on their school assignments and receive extra help when a parent needs to work at the CITC office.

The CITC leadership as a unit is really genuine. They make all employees feel valued. They care about what is happening at home in our personal lives. The message is clear that we are in this together and it’s about one step at a time. That really helps with morale and wellness of everyone. —Jesstella Vasquez, family mentor

Taos Pueblo

Taos Pueblo, a grantee since 2011, delivers PAT to AIAN and non-Native families with children prenatal to kindergarten entry living in a remote, rural reservation and non-reservation area in Taos County, New Mexico. The Tiwa Babies Home Visiting program is part of the Taos Pueblo Division of Health and Community Services and can serve up to 35 families.

Staff of the home visiting program started preparing in early March 2020 for COVID-19. Because of Tribal self-governance and being a small, tight-knit community, they were able to move forward quickly. Also, staff reflects that Tribal sovereignty (or self-control) creates an environment of mutual respect, determination to find solutions, and a commitment to community survival. In short order, they worked with the information technology staff to procure laptops and confirmed that all staff had cell phones for contacting families. By the second week of March, it became clear that in-person visits were no longer possible and events had to be cancelled. When the Tribe decided to send workers home and then to close the Pueblo, all felt safe and prepared for working virtually.

There is this intrinsic strength, fortitude, perseverance….a calmness and belief that we’re gonna get through this. —Ezra Bayles, director of Health and Community Services

Four things stand out as important to Taos Pueblo’s ability to navigate the pandemic: (1) a small but mighty team that is committed to co-creating solutions, (2) a nimble approach to working with families, (3) leaning into supports and resources from others, and (4) connection to their vast lands and culture.

Small Team Committed to Co-Creation

The home visiting program benefits from a team that is close-knit, has experience weathering past challenges, enjoys strong communication, and is committed to co-creating solutions. The four-person team enjoys a “can-do” spirit that team members suggest comes from the leadership style of program coordinator Katherine Chavez. “Katherine’s leadership helps us to navigate these uncertain waters. It feels like a real partnership. Her support allows us to make the best-informed decisions for families,” said home visitor April Winters.

Chavez emphasizes the importance of regular communication. When staff needed to work remotely, Chavez checked in with each person every morning to try to normalize the situation and keep the focus on how the home visitors could best support families from a distance. In addition to the morning calls, the entire team meets for 11⁄2 hours each week, providing space to reflect on their own COVID-19 responses. The program coordinator also provides bi-weekly reflective supervision to encourage resilience and strength.

The team works together to co-create solutions.

A healing garden at one Riverside-San Bernardino County Indian Health Clinic, Inc., location offers a place for staff to take a break and find solitude. Photo: Riverside San Bernardino County Indian Health, Inc.

“Chavez sets the tone for this,” according to Debra Heath, program evaluator. She has a steady hand and positive outlook, sending the message to staff that we can figure anything out if we work on it together. We may not have all of the answers, but if we remain open and curious we will uncover the best next steps.

Chavez is comfortable with trial and error. “I guess one thing about our team…we do a lot of planning together and have open and regular communication,” reflected Chavez. Indeed, their communication and planning helped them create a suite of policies that offer guidance on working from home, the different phases of lockdown and what home visiting would look like for each phase, and a checklist for how to conduct a safe socially distanced visit.

Nimble Approach to Working With Families

“The curse of COVID-19 is the inability to meet in person with the families. We are a small tribe and value personal contact. How do we re-create that in a virtual world?” pondered Bayles. Heath noted that the staff were skilled at determining what the families needed in the moment, which sometimes meant setting aside the PAT curriculum and focusing on immediate needs. By the fourth month of the pandemic, most families were ready to engage with the curriculum and talk about ways to support their children’s learning.

Lean Into Supports and Resources

The home visiting team found that sharing resources—either across agencies in Taos Pueblo, with the Taos Early Learning Committee, with the broader New Mexico early learning community, or with other Tribal home visiting programs nationwide—contributed to their success. For example, programs shared resources and information at meetings of the Taos Early Learning Committee. With this information, resource binders were expanded to include additional referral sources for families that might need financial help for rent or utilities, behavioral health support, or access to food. The home visiting team also participates in webinars and accesses training material via a portal set up by the Administration for Children and Families Tribal Home Visiting Program. They are continually searching for the best of what is available and then adapting it to Taos. “Home visiting has a very sharing culture,” said Bayles. “We found examples from others that would work and often turned them into tribal-wide policies.”

Connection to Vast Lands and Culture

In times of difficulty, the people of Taos Pueblo seek and receive comfort from their culture and nature. Though the parks may be closed due to COVID, the mountains are always open. Community members enjoy hiking, fishing, and any other activity in nature that connects them with their history and nurtures their inner strength. “Maybe we are not able to do our traditional activities in person, but we have all of that within us. We remind each other that the land, nature, foods, and song give us strength,” said home visitor Aspen Mirabal.

Riverside-San Bernardino County Indian Health, Inc.

RSBCIHI, a grantee since 2011, is a nonprofit tribally controlled and managed health care organization that delivers PAT to AIAN families with children prenatal to kindergarten. The service area includes both rural reservation lands and urban non-reservation communities in southern California. The Tribal Family Partners Program operates out of eight health clinics and can provide home visiting services to 125 families.

On March 20, with the COVID-19 pandemic taking hold, all in-home visits provided through clinic programs were stopped. “This is the most challenging thing we have ever faced as a health care organization. It’s the first time that we have had to open an emergency command center,” said Bill Thomsen, chief operations officer.

Social isolation is a concern, and many cultural and community supports families normally turn to are not available. Photo: Konoplytska/shutterstock

The company wanted all programs to use their telehealth platform. It took time to train staff so that they could fully understand the functions of the platform. Free Internet or an upgrade was available from the community. The diabetes program was first to resume services, and then the home visiting program followed suit with staff identifying ways to operate in a virtual environment. Company-wide policies helped to ensure consistent and safe access to services and job security for all.

Three things stand out as important to the ability of the home visiting program to navigate the pandemic: (1) connection to the larger health care company and the benefits that come with that—from policies and procedures that apply to all programs, to greater financial stability when the organization is not dependent on just one funding source; (2) commitment to supporting staff so that they can show up for families; and (3) strength from a powerful sense of community, family, and history.

Our sense of community is strong. We take care of our elders and our children. This is at the core of who we are. We create a circle of care. So we fly through disasters like these. We wake up and put our warrior hat on. —Bridget Lafferty, parent partner

Connection to a Large Health Care Organization

RSBCIHI is funded through the Indian Health Service and governed by a Board of Directors comprised of elected members from the nine tribes that make up the managed health care organization. It is a large multiservice company providing services to 17,000 patients. The home visiting program benefits from being nested within the company. Policies and procedures are developed by the Board, reinforced by the program directors, and applied company wide.

For example, COVID-19 policies define health and safety precautions. People are required to wear masks from their cars to the entrance, where all have temperature checks before entering the clinic. Signs on the floor remind all about the importance of social distancing. The clinic provides hand sanitizer, antiseptic wipes, and personal protective equipment. Information from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is shared with staff so they can stay healthy and educate families about safety measures. “Staff felt safe coming back to work,” said Jaclyn Gray, program director.

Because of the financial strength of the company, all staff were able to enjoy job security even when the future of their work was uncertain. When the decision was made to operate with a 3-days-on and 2-days-off rotating schedule in April and May, employees were guaranteed full pay. If they became sick or otherwise could not work due to COVID-19, they could use administrative leave rather than sick or vacation time. “They want us to take the time to make sure we are well before we come back,” said parent partner Teresa Castro.

Commitment to Supporting Staff

The home visiting program adopted programmatic practices to support staff and help them feel empowered. A consultant was hired for one-to-one reflective supervision. In addition, the consultant facilitated group sessions designed to provide a safe circle for staff. “This created an avenue to relieve some of the stress affecting the home visitors and helped to shift their mood to ensure a good mindset before connecting with families,” said Gray.

The program also created a buddy system for home visitors so that they can rest assured that the families in their caseload will continue to receive services even if the assigned home visitor is unavailable.

Mindfulness sessions, facilitated by a psychologist, are also offered during the lunch hour for all employees. The diabetes program provides fitness sessions that all can join. A healing garden at one clinic offers a place for staff to take a break, find solitude, and garden.

I enjoy working for the Tribal community because of that sense of care. It feels like I have an umbrella over me. And because I have that umbrella, I can be the umbrella for my clients. —Bridget Lafferty, parent partner

Connection to Community, Family, and History

During these stressful times, a deep connection and unwavering commitment to community, family, and history keep the home visiting staff focused on the reasons why they do their work. It also shapes how they do their work. For example, clinic staff are mindful that elders must come for appointments and so they take all precautions not to put them at risk. “We focus on our elders a lot because we are an oral tradition and keeping our elders healthy and being there so we can learn from them is a priority,” said parent partner Marilyn DelaOssa.

Virtual gatherings via videoconferencing help families minimize feelings of isolation and reinforce culture and tradition.

The theme of a recent virtual gathering was “Sharing Stories.” According to Castro, it started with a prayer that even the children could join.

Prayer helps us spiritually. You can’t just be physically well. To be 100 percent, no matter what you believe in, you have to be spiritually well too. One of our staff sang a traditional song and then we shared the story Raven: A Trickster Tale from the Pacific Northwest. We did a scavenger hunt for the children—find something warm, something yellow, a favorite book—and then we invited families to share their own story, prayer, or song. —Teresa Castro, parent partner

Lessons Learned

When COVID-19 began, no one predicted the extent of the pandemic and the programmatic and policy changes that would come to be. A year later, much has been learned as a result of the continuous observation, assessment, and adaptation by steadfast home visiting program leaders. Those leaders offer the following suggestions:

Administering the Program

- Be pragmatic and planful. When faced with a challenge, it is best to stop, think, and figure out how to navigate the issue. Baby steps forward are just fine.

- Give emergency plans a dry run to work out any kinks before they are needed. Think through the role and capacity of technology.

- Remember that the home visiting program provides essential services during times of crisis and keeping the program operating offers a necessary lifeline to families.

Supporting Staff

- When hiring, it is the intrinsic stuff—the commitment to service and family—that matters most. No amount of reflective supervision or policies can replace that.

- Invest in the health and well-being of the staff and provide concrete supports that help them approach work with a clear head and an open heart.

- Give each other grace. It is important to recognize and respond to staff needs, arrange talking circles, and encourage staff to care for themselves and each other.

Working With Families

- Build on cultural strengths. Activities that connect families with their culture are an asset during times of challenge.

- Find ways to deliver home visiting content while responding to the individual needs of families. Virtual group connections help reduce isolation.

- Maintain communication at all times, and especially during unusual circumstances. Let families know what is happening, changes to the program, and when and how you will follow up. Always keep promises.

Cook Inlet Tribal Council benefited from long-term leadership and a strong multiservice organizational structure, connection to values, and the adoption of practices to support staff well-being. Photo: Bildagentur Zoonar GmbH/shutterstock

Collaborating With Community Partners

- Develop relationships that you can tap for problem solving, sharing strategies, and leveraging resources such as emergency financial support for rent and utilities, food, and behavioral health services.

Closing

Each of the Tribal MIECHV grantees interviewed weathered the uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic in admirable ways. It helped that they started from a strong position. They already had solid relationships with families, referral partners, and community leaders. They were able to leverage those relationships to meet needs of families, offering a lifeline of support and friendship. While families were isolated in their homes, home visitors dropped off supplies; provided education and support around parenting in these unusual circumstances; organized virtual group activities to keep families connected to one another (and often, to their culture); conducted critical screenings and assessments; and ensured families had access to phones, the Internet, and technology so they could participate in remote visits. Home visitors also supported each other to get through these challenging times. They found ways to connect virtually as teams and made sure that all felt acknowledged. Self-care, compassion, generosity, and gratitude prevailed. Overall, Tribal MIECHV program leaders and home visitors remained hopeful and determined to adapt so that they could continue to show up for families and one another—providing a light of hope as only they know how.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to the staff and families of the Tribal MIECHV programs who shared their experiences.

Author

Deborah Roderick Stark, MSW, is a nationally recognized expert in child and family programs, research, and policy. She has more than 20 years of experience working with foundations, public agencies, and the nonprofit sector on behalf of young children. She guided development of Early Head Start in the Clinton Administration. As a consultant, she has authored or provided research for critical books, articles, and papers on topics including home visiting, family engagement, early childhood education, and infant and early childhood mental health. Stark can be reached at: drs889@gmail.com.

Suggested Citation

Stark, D. R. (2021). Sustaining a light of hope for families. Tribal home visiting programs persevere during COVID-19. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 41(4), 10–16.

Reference

Trust for America’s Health, National Medical Association, & UnidosUS. (2020). Building trust in and access to a COVID-19 vaccine among people of color and Tribal Nations: A framework for action convening. link